This post forms PART 1 of my family's adventures on a mini-break in Athens.

We often learn to love the place where we were born, even if it can't offer us what we want or even what we need. One day we may leave it, but that place will remain in our memory like a timeless snapshot that never changes, a kind of 'vie en rose' which we often refer to subjectively. We never remember the bad times, only the good ones, and wish we had never left, that we could go back and live there, even though we know full well that this is impossible.

Most immigrant Greeks and their children fall into this category. They continue to love and cherish the country of their birth by coming back on holiday every now and then, with some coming on a more regular basis. They are also constantly on the phone with relatives, they have access to Greek satellite TV in their homes, they educate their children in the Greek language and customs, and cook Greek food at home on a regular basis.

Try generalising this way of thinking to a large part of the Greek population who migrated from the 'eparhia' (επαρχία - the countryside) and came to live in the various neighbourhoods that make up the city of Athens. The word 'immigrant' probably sounds a little harsh, especially since we're talking about Greeks moving around in Greece. But there are many people living in Athens who look forward to a day when they won't be living in Athens any longer, and they'll be able to retire to their village homes in the countryside, the place where they were born. It wouldn't occur to many of us that there are so many people living in Athens (which houses about 40% of the population of Greece) without much choice, but the fact remains that many a Greek had to forgo their village homes for a place in the urban rat race that has trapped them, just like the economic migrants of today who are forced to leave their own country and follow their dreams of a more prosperous life in a foreign one.

Elefsina, a coastal area 18 kilometres west of Athens, was once considered the 'perfect' place for those unskilled Greek villagers seeking employment opportunities. Despite its importance in ancient times as the site where the Greek goddess of the Earth, Dimitra, performed her mysteries so well that, to date, no one knows exactly what went on during the rituals performed in her honour, Elefsina (formerly known by the name 'Eleusis') became a deserted ghost town after Christianity became the dominant religion in Greece, and it was only at the end of the 18th century that it began to be repopulated, with great interest shown in its glorious past by the travellers of the time.

Elefsina still has some empty sections of lands filled with olive trees, pistachio trees (the nut), wild horta and a kind of nettle that I haven't ever seen in Hania.

Elefsina looks like an ordinary town - until you catch sight of the huge unsightly factories built of steel and cement on the outskirts of the residential area. The cement works seen at the end of the road are now defunct, but its existence on the skyline creates an eyesore.

In its earlier years, Elefsina resembled a green village, its fields filled with olive and pistachio trees. As the town grew into an uncontrolled industrial area, it attracted rural Greeks from the poorest areas of the country (notably Epirus and Crete), who were attracted by the huge cement works, ship yards, petrol refineries, steel factories, munitions works and a whole host of other smaller industries and manufacturers, all of which wreaked dire consequences on the environment, therby becoming the most polluted area of Athens. By this time, Elefsina had become a veritable stinkhole, earning its appropriate reputation as the queen of the most unenticing place in the whole country.

Despite the negative outlook it portrays, I have a very good relationship with Elefsina, where quite a few members of my extended family live. Not many people realise that Elefsina's image has been completely cleaned up in recent times. Factories have moved on or simply died out, while those remaining have had to adhere to strict laws to protect both the environment and the citizens. Elefsina's neighbourly sense of community cannot be matched in most central areas of the capital. Most houses have gardens, apartment blocks are low-rise, while accomodation is spacious; Elefsina doesn't lack space, unlike the centre of Athens and its surrounding suburbs. People who have grown up in the area keep close ties with one another, preferring to remain in the area even after leaving the family home and creating their own.

When travelling in Athens, always look at the road signs. They are so full of history, that just reading their names will recall ancient Greek tragedies and bloody battles. Sometimes they are written in both Greek and English. As this part of the city is not touristy, these particular ones (located in Egaleo, a western residential suburb of Athens) are written only in Greek. The Holy Road (Iera Odos) meets up with the road to Thebes (Odos Thivon), which also intersects with Athens Avenue (Leoforos Athinon), a road linking Egaleo with Athens.

A well-known Greek song by a very famous 1970s singer (Manolis Mitsias) mentions Elefsina (click here to listen to it):

Πήρα τους δρόμους μια βραδιά (I took to the roads one night)

και τους γνωστούς ρωτούσα (and asked all the locals)

για το κορίτσι μου που αγαπούσα (about the girl I loved)

στην Ελευσίνα μια φορά. (one time in Elefsina)

Έριξα πέτρα στο γιαλό (I threw a rock into the sea)

στο πέλαγο λιθάρι (a pebble in the ocean)

για το κορίτσι μου που ήταν καμάρι (for the girl who was my pride and joy)

στην Ελευσίνα μια φορά. (one time in Elefsina)

και τους γνωστούς ρωτούσα (and asked all the locals)

για το κορίτσι μου που αγαπούσα (about the girl I loved)

στην Ελευσίνα μια φορά. (one time in Elefsina)

Έριξα πέτρα στο γιαλό (I threw a rock into the sea)

στο πέλαγο λιθάρι (a pebble in the ocean)

για το κορίτσι μου που ήταν καμάρι (for the girl who was my pride and joy)

στην Ελευσίνα μια φορά. (one time in Elefsina)

Elefsina is not without its famous people. A well-known contemporary ballad singer was born here, Stelios Kazantzidis. Before he died of cancer in 2001, his request to be buried in Elefsina, came as a surprise to most Athenians, who like to maintain the elitist belief that important names in Greek history are always buried in what is known as the First Cemetery of Athens.

*** *** ***

Petros Agrimakis (or in Greek, Πέτρος Αγριμάκης) was born in Rethimno, Crete. He left his birth village when he was just a baby, along with his four older siblings and their parents. They settled in Elefsina where jobs were plentiful at the time. It's easy to think that Petros has never known any other place to call home, except for Elefsina; after all, he feels himself to be a true Elefsionioti, as all his family still lives in Elefsina and his friends all derive from the area.But Petros has never hidden his Cretan roots. He met his wife at a Cretan dance school in Elefsina; her own parents were born in Hania (she herself was born near Elefsina). His sons both attended the same Cretan dance school that their parents attended, and every year, they visit Crete, not just in the summer on vacation, but whenever a visit to Crete is called for: maybe someone's getting married or baptising their child, or there could be a funeral of a distant cousin; then there's the 40-day and 12-month memorial services after someone has passed away.

Greeks usually identify with the place where one (or both) of their parents were born and raised. The move to Athens is seen as an inevitable consequence of modern life, but it does not mean that the former family 'home' is forgotten. Petros is a prime example of someone who has a strong connection with his roots; he has built his whole life on them.

Being a businessman by nature, his many projects have culminated in the opening of a Cretan restaurant in Elefsina.

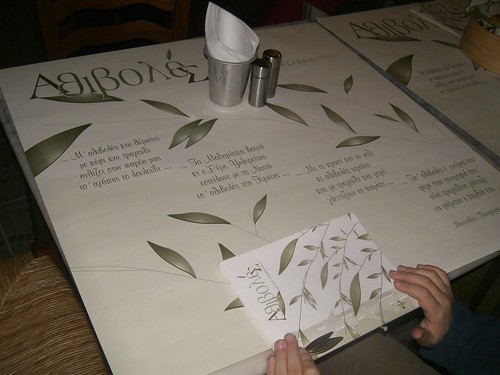

Athivoles Mezedopoleio is housed in the yard (covered and heated in the winter) of a former stately home on the main commercial road in Elefsina. The kitchen and more seating are found indoors on the ground floor.

Deciding what to serve at the restaurant was easy: Cretan food. It took him longer to decide the name of the restaurant than it did the menu. The message Petros wanted to get across to his potential clientele, mainly other Elefsinians like himself, was his memories of the place where he was born; the word 'athivoles' is part of the Cretan dialect, meaning 'memories'.

It recalls older times when people were not hurried, and still lived all their life in the place where they were born. Cretan music is played all through the night, while the decor includes significant reminiscences of Cretan life, with olive motifs on the menu card and dried herbs hanging on the wall.

Athivoles was the first place we went to when we arrived in Athens on our mini-break. It was a busy night when we visited.

Snails form an integral part of the Cretan diet. The creamy dip is tirokafteri, while the little pot of meat is called 'tigania', fried pork cooked with slivers of peppers and melted cheese.

This greengrocer proudly states his origins on his shop sign: he comes from Zakros in Eastern Crete. I snapped this from inside an Athens bus.

If you can't make it to Crete on your next visit to Greece and you're staying in Athens, you can still get an authentic taste of Crete just by asking for directions to the closest Cretan taverna in your neighbourhood. Just look for the shape of the island of Crete on a sign above a shop. If you hear Cretan music playing on the radio or from a CD, you can guarantee that a Cretan is meddling somewhere in there; listen out for a mantinada.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.