Last Sunday, on St Demetrius Day, it was open house at our place. We clean up the house, we prepare a lot of food, and we wait for our guests to come. St Demetrius Day is my husband's saint's day, the day he celebrates his name. We never invite people to our house, but they never forget to come, either; friends' and family namedays are much easier to remember than birthdays, and for this reason, it is seen as an obligation of the guests to either visit or phone the celebrant and pass on their good wishes to his/her family.

So what does Organically Cooked prepare for her husband's nameday? You can imagine the fuss in my kitchen, the mayhem that must be taking place, as everything must be in order and only the best will do for this day. You must be envisioning mezedakia of all shapes and colours and main courses to explode your mind being prepared frantically all the week, in preparation for their final bake-off. And being the venerable cook that I am on such an auspicious occasion, there is no leeway for erroneous actions. Hence your bewilderment at the sight of the boxed frozen food: pizza, kalitsounia, crepes and meatballs, along with some store-bought cakes and sweets. Allow me to explain myself.

A typical week in the life of Organically Cooked starts off with Monday morning: that's when the mayhem starts, without needing to prolong or re-create it in the kitchen at the weekend. On Monday morning (one of my two no-office-work days), I have to prepare Tuesday's meal (or both Monday and Tuesday's meal, if I hadn't prepared that the night before). After getting the kids up, preparing their breakfast and dropping them off at school (primary schools in Greece start by law at 8:10am), I buy our daily bread and milk needs. Our favorite bakery supplies the INKA supermarket chain in Hania with the full range of white and brown bread, rolls, burger buns, baguettes, olive bread, cheese bread, bacon bread, you name it, so it only follows that I go to the supermarket and not the local bakery to buy a 3-day supply of bread and milk. This allows me to pick up any other bits and pieces that we may have run out of: ham and cheese for the children's sandwiches, stamnagathi horta now that we have no more vlita in our garden, maybe a pot of yogurt, the odd paper napkin, whatever I remembered to write down on my list.

After unloading the shopping, I need to start cooking. Whatever is on the menu for that day, I need to make enough to last two days so that there will be some leftovers for another day later in the week when I'm working again. Let's not forget the evening meal: if it isn't dakos or bread, oil and tomato, then I need to prepare it: pancakes, kalitsounia, a pizza; there's a cyclical choice of something different every night, all of which does the rounds every week.

Any errands to run in town? Maybe some irrigation or olive-harvesting in the village, the main job at this time of year in the fields. We like to harvest our own table olives; they need to be cured using various treatments. And did my uncles promise me a pumpkin, or some farm-fresh eggs? I need to go pick those up too, otherwise I won't get asked if I need anything again. What about a washload of clothes? "You've got a washing machine for that," I hear someone say. Yes, I do, but we don't have a drier, and neither do we need one with all that Mediterranean sunshine we get. Any dishes to clean? We only use the dishwasher when the kitchen bench top gets out of control; perhaps this is what forces everyone to clean up after themselves...

Time to pick up the children, after half-past three. Since I've had the day 'free', you may be wondering where the mayhem is. Six and seven year olds have no sense of responsibility concerning possessions: "Where did you leave your jacket?", "Did you forget your pencil case under your desk?", "What happened to your lunch bag?" By the time we get home, the countdown begins: we have approximately 70 minutes to have the main meal of the day and finish off any homework that wasn't completed at the afternoon session of the all-day school program (working parents use this state-provided service) before...

...Number 1 joins his fencing club, while Number 2 plays tennis. Fencing starts at 5pm near the old town gymnasium close to our house. Number 2 has a tennis lesson for one hour in the middle of town; her club starts at 6pm. While I drop off Number 1, I go back home to Number 2. We leave the house at 5.45pm and weave through the inner city traffic to go to the town's stadium for the tennis lesson. Meanwhile, Number 1 finishes fencing at 6.30pm; I go back to pick him up, only to go back into town to pick up Number 2 at 7pm. We find a parking spot and Number 1 gets fertilised and irrigated with some water and a home-made snack. If I didn't bring food from home, I'd have to buy some puff pastry crap to feed them with. I drop him off at the chess club for a one-hour lesson at 7pm. In the meantime, I dash back to the stadium (chess and tennis are located in the same area) to pick up Number 2, who also has her snack in the car. As a way to pass the time before Number 1 finishes from chess club, we do some shopping together: there are two good fresh produce shops in the area, as well as a (not-so-good) supermarket, and the best organic supplies shop in Hania.

By the end of the after-school activities session, I've been walking and driving up and down town like a yo-yo. But it's not only me: every night of the week during the school year, the roads of Hania (and every other town in Greece) fill up with yo-yo-ing mother taxi drivers. Practically every single mother in this town (and every other town in Greece) has become a yo-yo at some point in her life, ferrying children from one activity to the other. In my house where there already is one taxi driver, it seems as though we are doubling up on energy, but there's a saying in Greece that should explain why this is happening: "the shoemaker's children are never shod".

Some time after 8 o'clock, we're all in the car, on our way home. Then it's dinner, bathtime and the preparation of the next day's school meals: a packed lunch in a bento box.

(After the nameday party, we were left with quite a few boxed sweets, a very popular 'present' to bring to a nameday, hence their inclusion in the children's lunch the next day: baby bananas, a mini-roll sandwich, dakos and chocolate eclair)

Then a quick ckeck of the contents of the children's school bags. The evening is almost over; there's not much energy or time left to do much else anyway. The next day, I'm on a 9 to 5 basis at work. I really only have time to prepare a meal and check the children's homework and bags. The next three days are either like a Monday or a Tuesday. That leaves the weekend to do whatever wasn't done during the week: mending my daughter's trousers which she tears at the knees on the basis of one per week, tidying up the house, ironing, gardening. Let's not forget that we like to eat a decent meat-based meal on Sunday, and we also had to cure the olives we picked from the village. Don't we all need some time to relax, too?

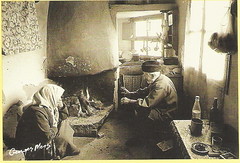

(A telling photo: my kitchen balcony - the children use the orange table for activity work on sunny days. I was cracking green olives here all morning Saturday. The plastic sheeting and newspapers were stuck on the wall to prevent the oil stains from the crushed olives splattering the walls. The gas bottle connects with our kitchen through a hole in the wall; mainland Greece has gas pipes, but not insular Greece. The crockery - the two large tubs, the tray and the overturned pot under the tray - are all from New Zealand, remnants from my mother's kitchen. The mallet belongs to my mother-in-law, but it looks as though I have already inherited it.)

It wasn't my intention to put store-bought snacks on the dining table on my husband's nameday, but that's all I felt I could cope with, given the daily routine we now follow with the children's schedules. St Demetrius fell on a Sunday this year, which means that the next day is also the start of new mayhem. Life is too short to worry about minor matters. At least tomorrow, there'll be a home-cooked meal, with the start of another round of the weekly mayhem.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.