When I first came to Greece, my monthly salary in Athens was 200,000 drachmas (approximately 680 euro, a little more than a starter's wage these days). This was supplemented with private lessons and editing work which were bringing in about as much as the salary, all at a time when a decent salary was considered to be about 150,000 drachma. Admittedly, I was working between 50 and 60 hours a week, but when you are young, you're remunerated well, you don't have other family responsibilities and you can enjoy your money, you are more willing to work long hours: you never get tired, you are full of energy, you don't even realise that you are working. My paycheck would go straight into a bank account; I never used it. All my expenses were met by the extra work: rent, electricity, telephone, utilities, food, bi-monthly weekend hiking trips to the Peloponese and monthly trips to Crete, my parents' homeland.

Despite being born and raised in a city, Athens was not the kind of city that could replace Wellington, the 12th best city to live in, according to

a recent Mercer study of the top 50 cities in the world. It bears no resemblance to it in any way, despite the fact that both cities are capitals; they are as alike as a pineapple resembles a walnut. Both are intrinsically tempting fruits, but ultimately, you have to decide which one you would prefer to eat on a more regular basis.

Mercer rankings are based on conditions that are difficult to measure in every part of the world in the same way. Wellington is a progressive modern city that has been in existence for less than 200 years, located in the last country of the New World to be colonised. In Athens, with its thousands of years of ancient foundations, every time someone digs a hole in the ground to lay pipes and chances on antiquities, ‘progress’ must be stopped in the name of ‘culture’.

|

| (A building site where ancient tombs were excavated; drainage works in the old town) one day in hania |

Life in a capital city of 400,000 where most people live in detached houses with lawn gardens simply cannot compare with life in a city like Athens of 4 million where most people live in boxes stacked on top of each other. Athens is a rat race, while Wellington feels like a huge field where its citizens live the life of grazing sheep.

*** *** ***

Whenever I was in

Hania, I felt as if I were in Wellington. Wellington is bound by sea and mountains - just like

Hania; the city centre is more compact - just like

Hania; life has a slower pace - just like

Hania. Crete may be an island (the biggest in Greece), but it doesn't have that air of island life that you find in the very small summer-only isles of the Aegean. For a start, most of the more populated areas are located on the north coast of Crete, which is bordered from the more agricultural part of the island by a small (but over-used) motorway. You never feel very far away from town life in Hania, even if you live in a village. It's no surprise that I eventually decided to give up my well-paid Athens job for a life away from the big smoke. I could only find piecemeal work in various English language institutes. Even though I was working in two institutes only a few hours a day, I still couldn't reach my Athenian starter's salary.

I accepted more work in a small town located on the south coast of Hania. At the time, Paleohora was a two-hour drive southwest of Hania (improved road conditions have now shortened the journey by half an hour).

(The first hotel in Paleohora - the Livykon, whose name is taken from the Libyan Sea - has a history of its own; it is now an earthquake risk and is slowly being renovated when funds permit; the main road in Paleohora is a hive of activity right throughout the summer, but not one of these chairs will be seen after October.)

(The first hotel in Paleohora - the Livykon, whose name is taken from the Libyan Sea - has a history of its own; it is now an earthquake risk and is slowly being renovated when funds permit; the main road in Paleohora is a hive of activity right throughout the summer, but not one of these chairs will be seen after October.)Having been to Paleohora on a few occasions to visit friends, I knew what I was in for: dry sunny weather for most of the year (the south coast is warmer and drier than the north with less rain), beautiful nature walks, the cleanest beaches, and all-night weekend partying; once the summer season ended, the restaurants and bars would open from Friday afternoon and work through the weekend, serving the town's growing population, and helping its citizens dispense with their accumulated wealth.

(Pahia Ammos Beach; Yianiscari Beach)

(Pahia Ammos Beach; Yianiscari Beach)

(The enticing waters of the Libyan sea: Yianiscari and Grammenos beaches)

(The enticing waters of the Libyan sea: Yianiscari and Grammenos beaches)Every Friday morning, I would take a

KTEL bus from the dingy outskirts of Hania where the long-distance buses are housed (always make sure you've been to bathroom before you come to the bus station) to one of the most picturesque towns in the whole province. Paleohora bears no resemblance to Hania.

(Nature spot at Grammenos Beach; the view from the hotel)

(Nature spot at Grammenos Beach; the view from the hotel)It's one of the places on the island that clearly reminds you that you are on an island and not an urban centre. It is located on a slightly remote peninsula that is bound by hills high enough to act as a natural border, giving the whole area an island feel. I taught English from the early hours of the afternoon to the early evening. My students were primary and secondary school children in the area, who were always more lively than their counterparts in Hania. They weren't as bookish as the children in the town, but they were more street-wise. They warned me that when the weather turns really bad, the only channels that would play clearly were the Arabic ones from North Africa (not all main Greek channels were able to send out their signal to Paleohora, anyway, so I suppose some television was better than none). When they made a mistake in their response to one of my questions, one of the better-informed would call out: "Hey, are you from the highlands?"; if they responded incorrectly for a second time, they'd get asked: "Did you take a KTEL bus to come here?"

(I remember sitting on the border of this tree having a sandwich in the middle of winter. Not a table or chair in sight, an empty beach, not even a car; just me and the sounds nature; I often stayed at this hotel: I felt as if I were in van Gogh's bedsit)

(I remember sitting on the border of this tree having a sandwich in the middle of winter. Not a table or chair in sight, an empty beach, not even a car; just me and the sounds nature; I often stayed at this hotel: I felt as if I were in van Gogh's bedsit)For lunch, I sometimes ate at a traditional

mageirio or a friend's house; sometimes I even ate a packed lunch al fresco by the beach, with not a sound to be heard but the wind and waves. In the evening, I chose something from the menu of one of the grillhouses in the area.

(Votsala Beach)

(Votsala Beach)Before the school term ended, I usually spent a three-day weekend in Paleohora sometime in May when the cold weather had abandoned the area, before the harsh summer heat overtook the whole area for nearly a third of the year. My favorite walk was to take the road right around the peninsula that forms Paleohora, walking up the steep rise of the small hill in the centre of the peninsula, housing the ruins of a former fortress, dated to the 13th century, which was used to guard against incursions.

(Views from Fortezza, also known as Selino Castle)

(Views from Fortezza, also known as Selino Castle)The infamous Barbarossa destroyed it, and its ruins were recently restored to a level that makes it safe for even young visitors to explore and pretend to be looking for pirates and lost treasure.

Another of my favorite haunts to explore was Gavdiotika. People from Gavdos island, the most southern point of Greece (in fact, it's

the southernmost point of Europe), were some of the earliest permanent residents of Paleohora. The first houses that they built are found near the port area. Gavdos Island is clearly discerned from here when there is no mist surrounding it.

Despite

its more recent settlement - it was never a traditional Cretan village - Paleohora has suffered the brunt of all the wars that have influenced Greece and Europe, with its share of losses.

*** *** ***

Paleohora is a great family destination, well-known for good chill-out beaches, a relaxed atmosphere, car-free evenings in the central part of the town and

very good food at low prices. The peninsula it is located on is small enough to give you the feeling that you are on an island; if you stand in the middle of the main road, you can see the sea from both sides of the street.

(Paleohora peninsula viewed from Fortezza; Pahia Ammos is barely discernible on the left, but Votsala and the port on the right are not visible)

(Paleohora peninsula viewed from Fortezza; Pahia Ammos is barely discernible on the left, but Votsala and the port on the right are not visible)

(The centre of the town; the port area next to Votsala beach; Pahia Ammos beach)

(The centre of the town; the port area next to Votsala beach; Pahia Ammos beach)Paleohora has an open-air nightlife that will suit everyone's tastes, and some kinky arts and crafts shops to add a touch of the alternative, catering especially for people who want to get away from the main town without getting too far off the beaten track. Some of the best Cretan New Zealanders are now living in Paleohora; if you aren't from Wellington, it's a little difficult to understand why a hotel-cum-restaurant by the sea is called 'Oriental Bay'.

(Oriental Bay, Paleohora; an Antipodean umbrella clothesline at the hotel; Oriental Bay, Wellington)

(Oriental Bay, Paleohora; an Antipodean umbrella clothesline at the hotel; Oriental Bay, Wellington)

(Beach gear; wooden hand-made items crafted by a senior citizen)

(Beach gear; wooden hand-made items crafted by a senior citizen)To get to Paleohora is quite a hike, despite the considerable road improvements. The road leading away from the north coast looks very fertile with its patchwork mosaic of olive fields.

(Fields of olive trees; a villager prepares for the winter)

(Fields of olive trees; a villager prepares for the winter)The soil is reddish-brown, the land is flat, and the area is covered in trees. On the side of the road, instead of rocks and stones as one sees when

travelling to Vathi, there are piles of chopped branches; somebody is getting the fireplace well-stocked for the winter. The fertile red earth on the flat fields is perfect for cultivating olive trees.

The point where the rocks start is also the where the long and winding road begins: I still get an upset stomach on those bends. A few stops are sometimes needed to catch a breath of fresh air before continuing to climb up the bends to the highest village -

Floria, where it usually snows in the winter, cutting off the road connecting the north to the south - before descending the mountain on its other side, and heading for the south coast.

The first rocky hillside comes into view at the village of

Kakopetros, a name meaning 'bad stone'. Rocks and trees intermingle, each one struggling to conquer the area. A long stretch of road after this point is constantly under construction. Ever since I started frequenting the area (over a decade), one or another part of that windy road is always under construction. Excavation machines, rock crushers and heavy rollers make it seem like child's play; the original road was carved out by men with pick-axes. It is amazing to think that from those rocks grow olive trees that produce some of the highest quality olive oil in Crete. Oil from the

Selino mountain ranges is considered the best in the world.

One tree-lined village after another, all sporting a kafeneio and maybe a church near the main square; two or three old men holding onto their self-fashioned walking sticks, arms resting on table, legs outstretched; not a woman in sight. Have they just come from the fields? Aren't they too old to still be working the soil? Where have all the young men gone?

And so it goes on, until the

Libyan sea comes into view on the south coast; you are now not far from the narrow tree-lined road that leads into the peninsula that forms Paleohora, almost an island itself, bound by the craggy mountains and the clear blue deep waters of Paleohora's coastline.

(When the coast comes into view, you are five minutes away from Paleohora; the road leading into the centre of the town)

(When the coast comes into view, you are five minutes away from Paleohora; the road leading into the centre of the town)*** *** ***

Paleohora is a summer lover's paradise. Bay after bay of clear blue water with the sun sparkling on it as if someone has thrown diamonds on a baby blue satin sheet, secluded beaches for that off-the-beaten-track feeling, an outdoor nightlife suited to the coastal location coupled with the hot dry climate

. Crete offers one of the highest numbers of 'blue flag' beaches in the whole country. Don't come to Paleohora in July and August without having previously booked a room, as all the hotels are running on a no-vacancy basis, usually filled with Northern Europeans and mainland Greeks yearning to chill out and darken their skin a shade or two before going back to their air-conditioned offices or the mouldy climate of their homelands

. September is always cooler, enticing the retired, the aged, the backpack-cum-walking-booters, coming to explore the lunar landscape of the rugged coast, braving the scorching sun and dirt-blown paths. There is very little natural shade; a few carob and tamarisk trees are of great assistance but they do not suffice. Sun hats are a basic essential, while umbrellas are a welcome sight on the beaches, some of which are stony, others sandy.

(The road to Yianiscari beach on the east side of the Paleohora peninsula; the road had to be excavated to provide access to the area - rock and sand dominate the landscape.)

(The road to Yianiscari beach on the east side of the Paleohora peninsula; the road had to be excavated to provide access to the area - rock and sand dominate the landscape.)

(Painting rocks at Yianiscari beach - an artist's view of the area behind the beach)

(Painting rocks at Yianiscari beach - an artist's view of the area behind the beach)

(More views of Yianiscari)

(More views of Yianiscari)September is also bird-hunting season, adding another element to Paleohora's mixed society of visitors. Hunters can be seen sitting at the kafeneia, wearing their camouflage gear, boasting about how many birds they caught that morning, discussing the best spots to wait for passing migratory birds making their way to Africa; ortiki (ορτύκι) - quail - and trigoni (τριγώνι) - turtledove - are the ones sought after by hunters this month. If the direction of the wind is in their face, it's a good flying day, but not a good hunting one; if the wind blows onto their tails, then

the hunters are going to have a field day, as these weather conditions make it difficult for birds to fly smoothly. When it's not windy at all - this is rarely the case in southern Crete, with winds high enough to send all the outdoor furniture to the other side of the peninsula - birds are slowed down in their passage, and may sometimes hide in a tree, waiting for more suitable climatic conditions.

(A lucky day for one particular hunter - trigonia: turtledoves)

(A lucky day for one particular hunter - trigonia: turtledoves)These birds' stomachs were filled with black sunflower seeds, which shows were their last dinner came from: Bulgaria, where the fields are covered in sunflower plants.

*** *** ***

Paleohora is also a place to enjoy

Greek cuisine at very low prices. Wherever you look, the food promoted in the menus and display cases of the restaurants, takeaway shops, bars, cafes, anything connected with the food industry, looks enticing. There are few empty seats by the tables of most of the eateries throughout most of the day. In the evening, the foreign tourists, used to eating an early evening meal, eat first, followed by the Greeks, who eat their evening meals much later. Most pensions and hotels contain self-catering facilities, but why stay indoors to eat, when you can sit outside and eat an excellent (and cheap) meal, in the traditional Greek flavours, prepared by someone else, so that you can breathe the fresh air, take in the magnificent scenery and enjoy the splendid view of the sparkling Libyan Sea?

(Almost fully booked - the whole night)

(Almost fully booked - the whole night)What astounded me most about the food served in

the restaurants of Paleohora was its price. The cost per day for our food needs (a family of four) is approximately the same amount of money needed for one meal out in Hania. How do they manage to keep their prices so low? For a start, most restaurants are owner-operated on personal property, so most people do not pay rental costs to use the land. They just have their business and maintenance costs. But the rest does not add up: the harsh sunlight and the dry conditions - there is a constant water shortage in the area - could not possibly harbour verdant fields and a flourishing agriculture in the summer, as it does in the northern area of the province of Hania...

Many people think of Paleohora as a tourist town. In the winter, it suffers from the great winter closedown: the only thing moving on the street in the afternoon in the middle of winter by the sea-front are the moulting leaves from the trees. Tables and chairs are stacked up in front of the restaurant doors; the locked-up look settles in the air, rendering the whole place a ghost town. Where does a population of 2000-strong (and constantly growing) go in the winter when none of the hotels are working, when the bars, cafes and restaurants have closed down after the last charter flight out of Crete, and the sea starts to roll in the waves that crash onto the main road? Not to mention the treacherous road conditions when the weather turns nasty, and snow cuts off the main road to Hania. What do people do here after the summer?

(The newest suburb of Paleohora, Panorama, as seen from Koundoura; the rugged coastline of Yianiscari)

(The newest suburb of Paleohora, Panorama, as seen from Koundoura; the rugged coastline of Yianiscari)Many Paleohorites often take their vacation in November and December, if family responsibilities permit. In January, they work in the olive fields: the area surrounding Paleohora contains olive trees producing

high-grade olive oil. Most people in Paleohora are not from the town itself; they settled here for work reasons, while their home base is some village close to Paleohora, where their parents and grandparents are from, and where they own ancestral land, cultivating olive trees that are already a century old. It is very tough work, but it also provides a good source of income. But not everyone in Paleohora owns ancestral land. Most of the seasonal employees are economic migrants from Eastern Europe: they cannot afford to sit around waiting for the next summer season to start (usually in April), nor is it viable to leave the town and settle elsewhere looking for work; they have already migrated once.

Paleohora was settled in recent times since the opening of its port in the late 1800s, so it cannot be said to have had an established pattern of agricultural activity or other regular sources of income. So what do the locals do in the winter?

*** *** ***

We had been swimming at Pahia Ammos ('thick sand'), a wonderful child-friendly beach on the west side of the Paleohora peninsula; the refreshing waters of the Libyan Sea whet our appetite and food was on our mind.

(Pahia Ammos beach; the suburb of Panorama overlooking Pahia Ammos)

(Pahia Ammos beach; the suburb of Panorama overlooking Pahia Ammos)I offered to walk to the burger joint not far away from the beach and get some junk food for lunch. I returned to find the rest of the family drying off, waiting to be fed. We decided to leave the beach (we hadn't hired an umbrella or deckchairs) and search for a picnic spot. This is how we ended up in Koundoura.

Not many people know about Koundoura, a satellite village just 2 kilometres west of Paleohora; activity is transferred from the summer resort town to this agricultural winter village in the last month of the summer season, when the charter-flight package tourism that Paleohora subsists from slows down, coming to an eventual halt at the end of October. Koundoura is a greenhouse centre - there are quite a few of these on the southern coast of Crete - which provides many parts of Crete and the rest of Greece with out-of-season produce during the colder months of the year. The greenhouses can be seen from the coast, lending an alternative view to an otherwise rocky landscape mixed with lush foliage from the olive trees. The greenhouses look so orderly and uniform, just like the terraced houses in the London suburbs, one attached to the wall of the other, their triangular roofs forming a zig zag design along the hillsides, the white plastic sheeting reflecting the sun's rays on the clear blue skyline; their gleam dazzles the onlooker's vision.

(Greenhouses in Koundoura)

(Greenhouses in Koundoura)Driving through Koundoura, I was not surprised to find the greenhouses empty: the weather was scorching (there is always a temperature difference of 4 degrees Celsius between Paleohora and Hania), the grass and weeds on the side of the road looked sun-dried, with arid desert-like conditions prevailing. Nothing can grow easily in this heat: even the spearmint that was planted in the flowerbed of the hotel looked like dry nettle leaves, spearing forth from the ground which had been covered in small stones to stop weeds from sprouting; they would have a hard time surviving even if they did.

Koundoura is the preferred hunter's ground for birds and hare. Hunters come here and set up their tents under the few trees providing shade by Krios beach.

(Krios Beach; a camper marks his turf)

(Krios Beach; a camper marks his turf)When I first visited Krios, I thought it was a wilderness haven. Even the trees looked savage: gnarled trunks, bare branches, lying on sandy brown soil carried from the beach to the hills by the high winds. Everything that grows on it - grass, weeds, leaves on low-lying branches of all the trees, even the bark of the trees themselves - gets eaten, torn or ravaged by the goats that the modern-day Cretan shepherds have left to graze in the area, feeding off pristine land that no one has ever laid their hands on.

(A carob tree, showing signs that it is used by goats; the sun playing games on the sea)

(A carob tree, showing signs that it is used by goats; the sun playing games on the sea)

Then there are the illegal poachers who come to the area in the middle of the night with torches, shining a low light on every inch of the mountainside, in the hope of dazzling a hare (or three), which, upon seeing the light, stands in the same spot, dumbstruck, without realising that all it has to do is run for its life to stay alive. Instead it stands there, like a lamb being led to the slaughter. It suddenly struck me that the greenhouses that I had just passed as we drove through the village must be leaving pesticide residues that somehow run off into the water stream; they are right next to the sea, right above the most alluring coastline in the whole province...

(Grammenos beach)

(Grammenos beach)Koundoura, for all its paradoxes, is the lifesaver of the region, providing agricultural winter work once Paleohora's summer tourist industry closes down. Each one complements the other, and this is what is helping the town to grow in population - and size. Paleohora now has a brand new suburb; new apartments have been built on a height overlooking Pahia Ammos beach - appropriately called "Panorama" - providing houses for the growing population, the offspring of the children of the older residents who decided to stay on the remote town, that they didn't need to leave their hometown after all, that there was a life worth living on the south coast of Hania, away from the bright lights of the old port and the urban sprawl of the main centre. Along with them, the economic migrants are probably happy to have work all year round, and to live in a small community where everyone knows the value of another person, socially, financially and spiritually; once the town closes down to visitors and retreats, the community keeps itself active with family responsibilities.

In amongst the double standards of the Koundoura habitat, we did find a place that provided us with a sense of inner peace. We had a hard time finding a shady spot to have our burger meal; all the coves and bays were exposed to the midday sun, Krios beach was overtaken by hunter campers, the greenhouse-lined roads were not at all alluring. My eyes caught sight of a dead end side-street, flanked by more greenhouses, which ended up at the sea; we could see it from the road we were driving on. We decided to investigate. The greenhouses were in a despicable state: dilapidated, abandoned; one of the walls of one had toppled over, and was beyond repair. Next to it was a house, plain and boring in appearance, the kind that would never attract the attention of a potential buyer, completely hidden from view, not a soul in sight. The iron fencework had been thatched with black nets, the kind used in olive picking (they are laid on the ground, the olives fall on them, either by being shaken or naturally, after which they are gathered and poured into a sack ready for crushing), so that the house looked barricaded against any intrusions. Tamarisk trees bordered the house from a gully which probably filled up with water during a heavy rainfall; despite the desert landscape of the area, it has suffered from flooding, in which a bridge was completely washed away a few years ago, breaking off communication between Paleohora and Koundoura.

(Lunch in a shady spot on the back of our pick-up truck)

(Lunch in a shady spot on the back of our pick-up truck)

(Imagine this to be your back yard; our view directly in front of the truck)

(Imagine this to be your back yard; our view directly in front of the truck)A makeshift gate had been erected as a way to keep access to the beach directly in front of the gully private. Thankfully, it wasn't locked. We had our lunch on this path, serenaded by the wind rustling among the leaves of the trees that provided shade and the lapping waves on the shore. The beach was rocky and uncomfortable; it was bordered by rough slippery rock, unsuitable (and probably dangerous) for swimming. But the water was that unmistakable Mediterranean blue. It was a day to remember, the first time in a while that I had been away from any form of artificial sound whatsoever.

*** *** ***

Clearly, Paleohora is not able to supply its own food needs in the summer, even though it provides food for the whole of Greece in the winter. The hotelier explains:

"Restaurants are supplied by fresh produce from the market in Hania. We can't grow much in this heat. Some people maintain a garden on their home property, but most people are too busy to do that in the summer. In any case, we don't have any spare land to do this; we've built the whole lot up with rooms for tourists. Most people don't have much garden space in the town; every spare bit is used for tourist-related activities. Only the newly built houses in Panorama have gardens, not down here (the main town)..."

Is 'local food' an issue for these restaurant owners? Do they voice an opinion about where their fresh produce comes from? How far have those salad ingredients travelled to get to my Paleohoritiko plate?

The hotelier continues:

"My sister has planted greenhouse cabbages and lettuce twice in the past fortnight, and both times they have dried up (early September). Lack of water, dry conditions, hot weather, they all take their toll on fresh produce. You need to water them every day, maybe even twice a day to keep them going until the cooler weather comes. It's better when the wind blows, even if it's a strong one. Anything to cool us down here..."

And yet, the food is cheap. For the last two years that we have taken a mini-vacation in Paleohora, my family paid an average of 53 euro a day for two sit-down restaurant meals per day for the whole family (2 adults, 2 children), including dessert and breakfast snacks. Of the many restaurants we tried during our recent three-day stay (this is our summer vacation, even though it's only 70 kilometres away from home), I would say I have two favorites, but as the hotelier told me, "

ALL the restaurants sell good food at a low price; there is nothing to choose among them, since they are competing against each other for the same business."

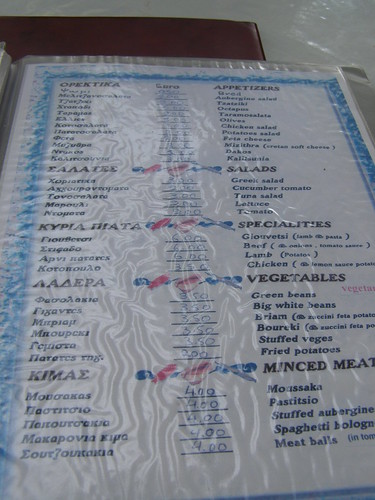

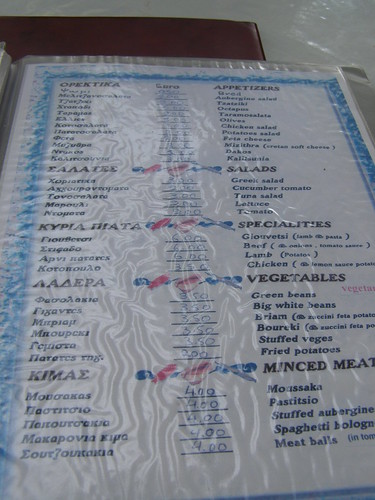

The Wave (Το Κύμα - To Kima) is idyllically located by Votsala Beach, on the east side of the peninsula. It offers the closest seats to the sea, shaded by some carefully tended tamarisk trees. They are the key factor to attracting customers - unless you know how low their prices are. Their menu is compact with little fanfare: they serve standard Greek and Cretan food, the kind of meals most women will be cooking on an everyday basis around the town itself. The items on the menu will be familiar to the most ignorant tourist foodwise (the Brits are a classic example) and their menu does not change from year to year; they have a standard culinary repertoire and cook their food to suit the palate of even the fussiest eater who does not eat Greek food on a regular basis. Their menu is cleverly drawn up, including everything a tourist will expect to find at a Greek restaurant. But just look at their prices: the servings were too large for the average tourist.

Everything stated on the menu is available, a sure sign that they know their custom well and how much of each dish they need to have prepared each day. Our last meal there was a mince medley: a large serving of

pastitsio (serves 2 children),

soutzoukakia (3, accompanied by french fries),

biftekia (3, also accompanied by french fries),

a Greek salad, an extra order of french fries, 2 cold tap beers and 2 lemonades cost only 25 euro. We were eating a sit-down restaurant meal at a cost of 6 euro and 25 cents each. Perhaps the German couple who came and sat directly in front of us ordered a hot (Nescafe) coffee to go with the ice-cream sticks they had bought from a mini-market because they did not know how cheaply it would work out for them to eat here...

Admittedly, the potatoes were pre-cut frozen chips and the meat patties looked too uniform in size to be home-made (and from past experience, I know that the 'fresh' green beans are always frozen), but for the price, the view, the location, the shade, the friendly owners (one of my former English students), and the peaceful atmosphere, they are really quite unbeatable.

Porto Fino Pizzeria stands mid-way between the ferry port and Votsala Beach. Pizza and pasta are its main meals, as its name suggests, and it is a popular young people's food hangout, if they aren't snacking on souvlaki or burgers. It does a great job with spaghetti puttanesca, and we also enjoyed an oven-baked spaghetti bolognese which I'm dying to repeat at home some time in the future.

(Porto Fino; cheers!)

(Porto Fino; cheers!)

Pizzas are unashamedly made in the standard Greek way (with canned mushroom segments; the risotto was probably made with par-boiled rice), but everything tasted so good, and the atmosphere could not be bought at any price. One pizza special (8 pieces), one spaghetti bolognese al forno (serves 2), a large tap beer, two lemonades: 20 euro, served with a free gimmicky sorbet (we've had lemon, blackberry and orange so far) in a shot glass at the end of the meal.

(It's easy to tell the locals and the foreigners apart...)

(It's easy to tell the locals and the foreigners apart...)A popular menu choice in most Cretan restaurants is a slight variation to Greek salad, known as Cretan salad. I ordered it at Captain Jim's taverna, situated across from the ferry port of Paleohora. Instead of feta cheese, mizithra is sprinkled over the salad, with a few tiny cubes of graviera cheese. Bread is unnecessary as an accompaniment to this salad, as it contains Cretan barley-rye rusks, broken into large chunks. Olives are not optional in this salad; they are deemed an integral part, for there are few meals a Cretan partakes without a bowl of olives accompanying them. When Cretan salad is made with heirloom tomatoes, garden fresh green banana peppers (not the hot variety) and cucumber, a tart and spicy onion, and Cretan olive oil, it is a sensation of senses: it looks, feels, smells and tastes heavenly. Listen to the sound it makes when you mix the olive oil into the other ingredients...

(Dakos rusk, oven cooked okra, Cretan salad)

*** *** ***

On the last day of our vacation, we decided to leave in the late afternoon and to enjoy a meal in one of the pretty villages we had driven past on our way to Paleohora. We drove for what seemed like a long time before we came across any light coming from inside one of the kafeneia and village restaurants by the roadside. The shop owners - they were still in their aprons - were usually the only people sitting outside enjoying the cool September breeze, chatting with the odd villager who had ventured out to buy something from the bakaliko (μπακάλικο - the general store); everyone else was at home, the lights of the houses attesting to this. We decided not to stop off anywhere after all; as soon as we entered the motorway, it was home sweet home on our minds.

Και του χρόνου (ke tou hronou), Paleohora, we'll see you next year, too.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.