The baptismal sacrament in the Greek Orthodox church is probably the most joyous one, the one that does not involve a great change in one's life, nor dealing with sadness, afflictions and confusion. It is a lasting one, so it is said, unlike the sacrament of marriage whose status can change over the course of time. Achileas had been instructed by his parents never to turn down an offer of becoming a godfather, which is how he ended up with four godsons, all of whose parents were distant relatives of his parents. The family of the last child he christened was quite a case in point, the one that made him realise he could not keep accepting godparenting offers in the future.

Stavros was Achileas' third cousin; this fact was disputable, as no one could quite remember the names of the great-great-grandparents, all long gone now, involved in forging this relationship. Before his parents' deaths, Achileas had only met Stavros, ten years his junior, once, at a funeral. Stavros had not made a favorable impression on Achileas at the time: a thirteen-year old black-shirted lad driving his father's pick-up truck. A mother managed to pull her child off the road before Stavros zoomed past the main square of the village which was filled with mourners.

Horiati, he thought to himself. Just over a decade later, his parents received a wedding invitation to Stavros' wedding, from Stavros' parents, as custom dictates: invite all the relatives, even if they don't know you.

"Stavros?" Achileas racked his brain to see if could remember who Stavro was. "Stavros who?"

"And he's marrying Persephone's daughter, Stavroula. Amazing how both sides of our family managed to get it together one more time!"

Achileas had little to do with either of the relatives concerned. Once he graduated from high school, he left Hania for Scotland, where he completed a Master's degree in Business Management. His marks were too low to pass into the school of his choice in Greece, so he preferred to leave the country and study abroad where he had a sure chance of being able to continue the studies of his choice, rather than play hit-and-miss again in Greece by sitting the university entrance exams again. He now preferred to keep company with the relatives he had more in common with, the ones who'd left rural life and become more urbanised. Not that he disliked the agricultural communities of his forefathers; it simply wasn't feasible to maintain both a life in the town working all hours of the day as an accountant, and then play the role of farmer-shepherd-horticulturalist-winemaker in his free time. By choosing the relatives he associated with, he felt a sense of content in that he was trying to fit the old adage "you can pick your friends, but not your relatives" more appropriately into his lifestyle. Therefore, he did not bother to attend Stavros' wedding.

The second time he saw Stavros was at his parents' funeral. They had both died tragically in a car crash. The congregation at the village church was far too large to accommodate the mourners; some of them he knew, others he didn't. A Greek funeral was like a wedding or a baptism: first you meet the couple, then you meet their children, then you say goodbye to them. Stavros had been living a comfortable life in the town, away from the familial bonds for so long, that he had neglected the oft-forgotten duty of remembering and honouring one's ancestors. The funeral had brought this fact home to him in the cruellest way. He felt out of touch with his own people.

Being an only child, he was very grateful to God - he wasn't sure who God was, but he did believe there was a superpower controlling the fate of mankind - that at least his parents had met his fiance, Korina. She was from the town, and shared his desire for a regularised urban lifestyle, away from the muck and bother of rural life. A pharmacist by trade, she worked shifts. When they had first met, she made it clear to him that she would not give up her job once she had children, something Stavros agreed to. He knew that this relationship of his could not be compared to his parents', where his father worked at the state electric company and worked the fields in his every spare hour, while his mother was a housewife, and turned the fruits of her husband's labours into various comestibles. His was a relationship based on equality, something he had got accustomed to during his six years in Scotland among the campus community. His wife was not able to continue Achileas' mother's constant adoration of him. The new woman in his life expected him to be strong and independent, like herself. Korina had helped to wean him off this kind of devotion. But he had never stopped loving his mother, who always had his favorite meal cooking in the oven, and had a stream of tupperware ready for him to take home with him after each of his visits. So when his parents left him together, he broke down. He had no idea how to start planning a funeral.

Korina's parents were very helpful in this respect. They contacted the head of the community in the village, who put Achileas in touch with Stavros. Stavros called the priest and made arrangements for the funeral, the opening of the family tomb - his father's family were all buried there right up to his father's grandparents - the

trimera, the

enniamera and the

koliva for all the memorial services ending in the 12-month

mnimosino. At the funeral, Achileas met Stavros' wife Stavroula for the first time; she seemed timid, quiet, reticent, more a young girl than a woman, carrying her first-born as if it were a piece of porcelain that she hadn't got the hang of holding correctly. It was after the

trimina memorial service that Stavros asked Achileas if he would oblige to his request to become the godfather of his son Manousos.

With the renewal of his family ties, Achileas and Stavros had now forged a dual relationship: they were both cousins and

koumbari. Achileas could not have turned his offer down, even if he had expalined to him that he had already become a godfather, after all the help that Stavros had offered and continued to offer to Achileas, even after the funeral and memorial services. He had taken him round the village and showed him the location and borders of every single field his father had been tending, including his mother's family's fields, which her siblings had been secretly hoping Achileas would never bother to find out about, so that they could trespass, with the hope that they could eventually claim it for themselves.

*** *** ***

Now that Achileas had a family of his own, Stavros' three children were the perfect playmates for his own two. They were similar in ages, and whenever they visited Stavros in the village, which was not often due to the pace of modern life and the various activities both families were involved in, seven-year-old Maria and nine-year-old Dionisis found an outlet to the expend pent-up energy that could not be used in the tightly enclosed space of a city apartment, no matter how large it was. Achileas had seconded the job to Stavros of caretaker of his fields, something that he now realised was essential if he were to maintain his father's olive fields in a tidy state, even if it meant that he produced just enough olive oil for his family's needs and did not make any profit from them. This was done without too much face-to-face contact with Stavros, as his cousin lived in the area himself. He preferred this situation to having to make regular journeys up narrow roads carved out from the mountains, with precarious driving conditions in the winter.

Whenever the families did meet, it was usually - nearly always - at Stavros' house. "Apartments aren't for me,

koumbare," he explained to Achileas. "I want to run like a goat, I need my space. I'd be hitting my head against one of the the walls if I was ever cooped up inside one." Stavros folded his arms under his armpits and moved them up and down like chickens' wings. "Dunno how you manage it yourself,

koumbare," he would tell him every time they met.

A favorite pastime of Maria and Dionisis when they visited the village was to check out the animals with the youngest of Stavros' three sons, Yiannis, who was the same age as Dionisis. Achileas was thankful for the contact his children had in this way with nature, but there was also the other side of the coin. The last time they had visited Stavros was at Easter, just when he had killed a sheep and had left it hanging to dry under the grapevine. He had felt a slight revulsion on first sight, as it had been a long time since he last remembered his father bringing home freshly salughtered meat. He knew his mother handled the chickens, but she had never let him watch her kill one, her way of protecting her one and only from all the bad on the world. His children did not seem perturbed in the slightest; perhaps it was Yiannis' mock taunting of the carcass that negated the psychological effects of such a sight and turned it into a game. In any case, he felt a slight sense of relief that he did not have to explain the process himself to his offspring.

Some time in the summer, just as they were ready to leave Stavros' house, Stavroula came out with a plastic supermarket bag containing a freshly slaughtered hen. She smiled as she held out the bag; she was a woman of few words. Achileas was used to his wife's dominating voice and he wondered, as he watched Stavroula, whether this simple woman who had never been to high school would have been a suitable companion for him; would it suffice to have food on the table and a clean house, as this was the whole of Stavroula's world. She did not work outside the home, she did not drive, nor did she accompany the children around to and from their schools and extra-curricular activities. Could the comfort and solace she offered replace Korina's organised mind? "Here," she said to Achileas, and gave him the bag. Then she disappeared into the kitchen, as if she had a good excuse to escape the farewell formalities.

Just at that moment, a shot was heard being fired, and there was a quick movement in amongst the vlita bushes in the garden. Maria started screaming and crying. As he tried to comfort her, Stavros walked by carrying a shotgun. Moments before, he had seen a cat entering the garden and had surreptitiously gone into the storeroom without anyone catching on to what he was doing. "Their blasted piss spoils the taste," he spat out as he made his way tot he storeroom to put the gun back in its place. He kept his rifle loaded at all times. "You never know who's lurking,

koumbare; one day it's an Albanian, the next, it might be a Turk." He sounded serious, as though he really believed what he said.

*** *** ***

In mid-September, Achileas found himself at the village once again, uninvited this time. It was Stavros' - and Stavroula's - nameday, and it is common practice never to invite guests to lunch. if they couldn't come, it was up to them to inform the celebrant. If their nameday fell during the week, Achileas would have called them and apologised for not being able to visit, citing the usual school-work-homework excuse. But today was Sunday. His wife happened to be working all day at the emergency pharmacy, so she would not be able to accompany him to the village. he would have to go alone; there was no excuse not to turn up. Korina had laid out the children's clothes for him so that he would not have to rummage around the wardrobes and drawers to find them himself, and had reminded him via an SMS to buy some cakes and to give Manousos some money ("

fakelakia top right-hand drawer of dresser") in lieu of a new-school-year present; now that Manousos had entered high school, it was difficult to choose a present for him anyway.

On leaving the motorway, they passed the greener lower-lying villages with their tree-lined streets and fountains surrounded by cafeterias, where some tourists were having a pit-stop as their coach was parked on the side of the rather inadequate road, given the increase in its traffic. Achileas pulled up near the coach to buy some sweets from the

zaharoplasteio in the area.

"I wish this was the village," Maria said. In some ways, so did Achileas, but he knew how cold and damp it could feel in the winter. Stavros' village - and Achileas' too, if only he could convince himself that he was no different from Stavros as they both shared the same family lineage - was located on a steep incline, which meant that flooding and damp conditions were not a worry to him. The main problem was the remote access; few people ventured up the narrow windy road that led to the village, and the residents there were all old, mainly women, one decrepit black-attired wrinkled bag of bones per five houses. Stavros had been very bold to renovate his parents' house and live here with his family.

"It's only half an hour from the town," Stavros would say to anyone who complained about the time he spent on the road. He dropped the children off to school on his way to work, and picked them up at the end of the day. He was a state employee, having gotten a position as an orderly in the hospital, and he had enough pull to bend the rules so that he could work the hours that suited him.

Achileas entertained the children by telling them stories about how he remembered the road when he was young.

"It was much narrower, and the bridge was very badly in need of repair, because it was constantly being destroyed when it rained," he was telling them.

"But it doesn't rain much in Hania," Maria said.

"It used to rain much more when I was young, dear."

"But if it rained a lot," his son was now talking, "why aren't there more trees on the mountains?"

"Climate change, I suppose, son."

"Oh," said Dionisis, as though he understood the expression; no doubt, it was something that had been discussed in shcool. Children were much more environmentally aware now than they were at Dionisis' age in Achileas' time. Being an only child, Achileas could not get enough of talking to his children. He had become a father much later than his peers and he felt grateful that he could offer his wisdom to them at an early age. He felt his mortality when he realised the age difference between him and his children. Like his parents who left the world before their time was due, he wondered if he would ever become a grandfather.

"What's this, Baba?"

A rocket-like instrument was lying on the ground next to what looked like a crater in the mountainside. Achileas explained to the children that in the past, the mountain, which was made of a grantite rock-like substance, was exploited for its use as a source for raw building materials. The hill next to the road was broken and the extracted rock was broken up into smaller pieces. It looked like a desecration of the countryside had taken place rather than any other useful exercise; the area had become an eyesore, and cretaed a ghoulish landscape where there should have been cypress trees, eucalyptus and mulberries.

*** *** ***

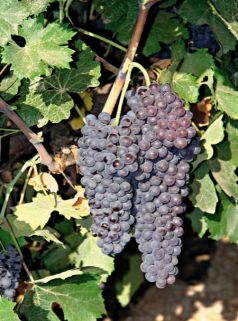

As they ascended into the thickness of the Apokoronas region, Achileas noticed a hive of activity in the fields. People were loading sacks onto 4x4 pick-up trucks. It was grape harvest time. At this point, he braked hard and the car came to a sudden halt. The children were admonishing him for making them crash into each other, but he wasn't listening to them. As he watched the workers haul up the sacks, he remembered his father bringing home the juice of the first pressing of the grapes of the season, and asking him, first, to put a glass of it to his ear to hear the fermentation process, then to smell it, and finally to taste it. He loved to drink it fresh with a couple of ice-cubes to cool it down, as it was always still very hot at that time of year, even though autumn was supposed to be setting in.

"What's wrong, Baba?" Dionisis was talking to him. He had been wrapped up in his own thoughts.

"Nothing son," he replied, as he set off again.

When they arrived at Stavros' house, all seemed quiet. Stavroula and her mother-in-law were sitting in the yard, which meant that Stavros and his sons were away at the fields, where he always spent his free time at the weekends, unless he was working one of the rare night shifts. He had converted an old store room in the house into a bedroom with an outhouse for his eighty-year-old mother; "two women can't cook in the same kitchen", he had once told Achileas.

"Χρόνια πολλά, κουμπάρα," he said to Stavroula as he gave her the box of sweets. "And here's something for Manousos," he added as he gave her 50 euro.

"Δεν έπρεπε, you really shouldn't," she insisted, even though they both knew that this was part of the custom of being a godfather.

"Come, come," Stavroula beckoned to them to sit down on one of the rickety woven chairs or the dried up cracked plastic ones in the yard. "Korina's at work, isn't she?" she asked, out of politeness perhaps. She could not understand why any woman would want to work, especially at weeekends. Her mother-in-law smiled and nodded her head. She was dressed head-to-toe in black, her grey hair swept into an untidy bun, a slight woman whose appearance had the look of weariness. Her fingers were short and knuckled, her cheeks bright red. She was wearing plastic slip on shoes over black nylon stockings, even though it was 30 degrees Celsius, and that was in the shade. She reminded Stavros of his own grandmothers. They had both died in the space of three years, the second one passing away only six months before his parents. "Better to bury your parents than your children," many people had said to him at the funeral in empathy.

"Stavros' at the

trigo," Stavroula informed Achileas. He had gathered that that was what he was doing, as there was a can of grape must (used to make grape syrup) boiling away over a makeshift outdoor fireplace in the middle of the yard. It added to the heat of the day, creating a stifling atmosphere. There was plenty of shade, though; Stavros carefully tended the vine above the yard simply for that purpose. Stavroula had disappeared into the kitchen for a minute and returned carrying a serving tray with a bottle of tsikoudia and some shot glasses. She had also arranged the

pastes Achileas had brought on a plate for everyone to help themselves.

The time passed slowly before Stavros' return. Achileas let the children run around in the yard, all the while worrying what Korina might say when she discovered that their clothes were dirty. Had she been here, she would have chastised them with her constant nagging; she was a cleansiness fanatic. Achileas was softer than his wife on the children. Being an only child, he had missed having company his own age when he was young, and this was why he wanted children - not just a child - as soon as ha and Korina married. They had decided that if their first born was a boy, he would choose the name, and if it was a girl, Korina would choose it. As it turned out, Dionisis was named after his paternal grandfather, as tradition dictates, while Maria was given her maternal grandmother's name.

Stavros and his sons - they had become fine strapping lads, all height and muscle - returned to the house after two hours. Yiannis was thrilled to see Maria and Dionisis. They scrambled off to the bedrooms - Achileas had forbidden them to go there in the absence of the occupants - to play with his toys.

"Ιντα κάνεις, κουμπάρε, σε χάσαμε!" Stavros greeted Achileas as if he hadn't seen him in years. He was sweating profusely, and there was still work to be done; Achileas helped him unload the truck with the sacks of grapes, ready to be poured into the wine press that he housed in a corner of his yard.

"

Kopelakia!" Stavros cried out to the children. "

Elate ne mpeite!" The five children trotted out into the yard, Achileas' children at first crious to see what was in store for them. He placed a white plastic chair near the tub and told them all to take off their shoes and socks. "Come and wash your feet before you get in," he instructed them as he carried a hosepipe to the chair and turned on the tap.

"Can we get in too?" Maria asked her father.

"Of course, honey, I'm going to get in myself!" Achileas rolled up his trousers, ignoring Korina's ranting face that was being played in fast forward motion in his mind. He helped the children out of their trousers and washed their feet. It was the middle of the day and boiling hot. This would end up being the best way to cool down in the sweltering

mesimeri. Everyone stomped and stomped until the grapes had become slush. Maria jumped up and down as if she were on a trampoline; her brother was not all that keen on getting dirty, but Achileas insisted that he had to stay in the tub until all the other children got out.

When the pressing was over, Achileas helped to rake up the remnants of the stalks and squashed grapes and place them in separate containers, to be used later in the month to make tsikoudia. When he had finished, he looked around to find his daughter. She had gone to the tap on the other side of the vat from where the must was slowly dripping out, and sat under it with her mouth open.

"

Kalo?" her father asked her. He had taken her by surprise. She spun round and looked at him, waiting for his approval. They burst out laughing together.

Stavroula in the meantime was preparing a feast. Achileas was not as carnivorous as Stavros' family was, but today he had worked up an appetite. After everyone had cleaned up and the must was poured into the various containers that Stavros had set out for this purpose, the yard was cleaned up and everyone helped to set up the tables and chairs. Stavros' second son, Yiorgos, lay the table. Manousos brought out all the dishes laden with food:

pilafi made with rooster, pork steaks,

garden fresh salad,

graviera produced from their own sheep's milk, and of course, a 5-litre

bottilia full of last year's wine to help the food go down.

Achileas started to feel the tiredness of the day wash over his body; he expected that Stavros and his family were probably also feeling very tired themselves, as they had put in a great deal of effort into turning this day into a succes

sful one. They farewelled each other and thanked one another for the company. Stavroula came out of the kitchen at this point, just like she two months ago when Achileas was last here, with a supermarket bag containing four bottles of grape must. She smiled as she passed the bag to Achileas.

"

Mousto?" He wasn't sure what Korina would think when he showed her the bottles.

"For making

moustalevria," she replied. Korina wasn't going to like the sound of this. Achileas realised that he was going to have to make the

moustalevria himself.

*** *** ***

Wine production in Hania is limited to self-consumption, despite the fact that the earliest evidence of wine production in Greece has been found on the island of Crete. There are cooperatives that collect wine must and turn it into a type of house wine that can be brought directly from them, but most wine production in Crete takes place in the region of Iraklio where there are also large companies that bottle and export wine to various parts of Greece, Europe and America. There are some vineyards in Hania that are involved in wine production on a larger scale, and there is some evidence that they will prosper, but that remains to be seen. It is generally the case that consumers are unaware of the wine production of Crete. The regions of Hania that do produce a lot of home made wine offer it for sale to tavernas and restaurants, as well as specialty stores for the general public. Apokoronas and Kastelli produce more wine than other regions in Hania, but it is possible to plant vines all over the island. Most of the houses in traditional wine-producing regions will have their own wine press tucked away in the yard, a vat-like tub made of cement; this is a sure sign that you will be able to find tasty barrel-aged wine (as well as tsikoudia) in that area.

There is no magic in making grape must, the first stage in making wine; it is a simple process seeped in ancient customs. Moustalevria dessert made from grape must is probably one of the most ancient cooked desserts known in Greece. It is made with two main ingredients: grape must and flour. The addition of nuts, sesame seeds and cinnamon came along over time, making a more attractive sweet. This sweet was very important in ancient times, as it is a sweet produced at the end of summer, and can be eaten freshly cooked, or sun-dried and stored appropriately as a dry sweet (like a hard jelly) for the winter. It is still made according to the original ancient recipe, which is an extremely simple one (there are

plenty of web sites featuring moustalevria).

Depending on the colour of the grapes used, moustalevria turns out in different shades of brown; green grapes produce lighter must than purple grapes, which in turn, produces lighter moustalevria. In all cases, the grape juice must be cleared of its residue. This was once done by throwing some wood ash into the mixture while it was boiling, or using

asprohoma (white earth). Although these are strained out of the must, modern day cooks may not wish to use (or may have difficulty in finding) either of these substances. In this case, careful straining of the liquid is advised, and you can still make an excellent moustalevria (I skimmed it many times while it was boiling, finally straining it into another vessel once it had cooled down). Just make sure you have fresh grape must, which you can even make yourself with just a few bunches of grapes, pressed into a large bowl. Some modern cooks prefer to use semolina instead of flour (I used a half-half mixture) because it does not go lumpy, which makes it easier to deal with, especially among people who do not have the luxury of extra time on their hands.

Fresh moustalevria is a jelly-like sweet that hardens a little over time. It does not keep well; the fermentation process becomes evident on its surface if it is not kept in appropriate conditions. But when it is left in the sun, cut up in small pieces, it goes as hard as a caramel. In this case, it does not grow mould, and can be kept in sealed jars and eaten as a sweet with tea or coffee. It looks quite unusual as a sweet; once you taste it, you can't stop yourself from eating too much. It is laden with the nutritious anti-oxidant properties of grapes, but it is also calorie-loaded...

Grape must is also used in making moustokouloura, large soft biscuits, good for dunking in tea or coffee. Moustalevria and moustokouloura are very important during fasting periods in the Greek Orthodox church, as they are made without butter, eggs and milk; they are some of the few sweets that can be eaten during this period, along with halva.

This is my entry for

Kalyn's

Weekend Herb Blogging hosted this week by Zorra from Kochtopf.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

The reason why the brothers do not harvest their grapes and make must together is manifold. For a start, the volume and quality from their share may be different, depending on the work put into the vineyard by each respective owner. But just as importantly, the must-making session involves the stage of congregation - each brother invites his own friends and relatives (which include their wives' families, work colleagues, koumbari) to join in the gathering, which is nothing short of a celebration, since all such events finish with a communal meal cooked by the hosts.

The reason why the brothers do not harvest their grapes and make must together is manifold. For a start, the volume and quality from their share may be different, depending on the work put into the vineyard by each respective owner. But just as importantly, the must-making session involves the stage of congregation - each brother invites his own friends and relatives (which include their wives' families, work colleagues, koumbari) to join in the gathering, which is nothing short of a celebration, since all such events finish with a communal meal cooked by the hosts. These seasonal events take such a hold over the participants, that they shut off any other worries or thoughts that may be gnawing away in their minds at the time, and they focus on the task at hand. Throughout the must-making event, there will be a lot of laughing, cheering and joke-making.

These seasonal events take such a hold over the participants, that they shut off any other worries or thoughts that may be gnawing away in their minds at the time, and they focus on the task at hand. Throughout the must-making event, there will be a lot of laughing, cheering and joke-making. That is, in fact, how the grape harvest we were invited to was played out. Only when it started raining did we remember the real world. The rain started falling while we were mid-way through our open-air meal. A λινάτσα was fastened under the grapevine that shaded us while we were eating, but that was placed there mainly to stop drying leaves, grape juices and insects from falling onto the table. When the rain came, it slowly seeped through the cloth, with the thick heavy droplets falling onto our plates and heads. The water gradually dampened our conviviality as we began to move the platters and glasses and wine (2x1.5L PET bottles, produced last year from the previous grape harvest) indoors.

That is, in fact, how the grape harvest we were invited to was played out. Only when it started raining did we remember the real world. The rain started falling while we were mid-way through our open-air meal. A λινάτσα was fastened under the grapevine that shaded us while we were eating, but that was placed there mainly to stop drying leaves, grape juices and insects from falling onto the table. When the rain came, it slowly seeped through the cloth, with the thick heavy droplets falling onto our plates and heads. The water gradually dampened our conviviality as we began to move the platters and glasses and wine (2x1.5L PET bottles, produced last year from the previous grape harvest) indoors. But the rain had done more damage than just to spoil the open-air meal - it subdued both our hunger and our thirst. We sat indoors glumly, listening to the pipes draining, and hoping that it would end soon. Even when it did, we did not continue to eat. The moans and groans took hold: "It wasn't supposed to come now, not today!" The children became edgy: "When are we going home?" The women thought of their chores: "I left a load of washing out - I wonder if it's raining in Hania." The men remembered that the final phase of the grape harvest was not finished yet: "The barrel is open! Cover it so that the rain doesn't seep into the must!" There is always a Plan B for when things don't go to plan, so that the ritual's offering is not wasted.

But the rain had done more damage than just to spoil the open-air meal - it subdued both our hunger and our thirst. We sat indoors glumly, listening to the pipes draining, and hoping that it would end soon. Even when it did, we did not continue to eat. The moans and groans took hold: "It wasn't supposed to come now, not today!" The children became edgy: "When are we going home?" The women thought of their chores: "I left a load of washing out - I wonder if it's raining in Hania." The men remembered that the final phase of the grape harvest was not finished yet: "The barrel is open! Cover it so that the rain doesn't seep into the must!" There is always a Plan B for when things don't go to plan, so that the ritual's offering is not wasted. The event finished a little earlier than had been hoped, but not before the job at the patitiri was finished. The continuation of the tradition took place in my house. I took home 3x4L plastic canisters of grape must and turned into seasonal offerings. Must has multiple uses before it is made into wine. Greeks use it to make a dessert with the addition of flour and nuts (moustalevria); they also make biscuits out of it (moustokouloura) and grape syrup (petimezi). The latter is considered a wonder cure for coughs and colds, and a preventive for winter ailments, as well as a vitamin supplement for the young, old and infirm. It can also be added to foods for flavour, to give them a sweet-sour taste. Grape must can also be used to make vinegar.

The event finished a little earlier than had been hoped, but not before the job at the patitiri was finished. The continuation of the tradition took place in my house. I took home 3x4L plastic canisters of grape must and turned into seasonal offerings. Must has multiple uses before it is made into wine. Greeks use it to make a dessert with the addition of flour and nuts (moustalevria); they also make biscuits out of it (moustokouloura) and grape syrup (petimezi). The latter is considered a wonder cure for coughs and colds, and a preventive for winter ailments, as well as a vitamin supplement for the young, old and infirm. It can also be added to foods for flavour, to give them a sweet-sour taste. Grape must can also be used to make vinegar.