The word 'horta' is the plural form of 'horto', meaning 'grass' - not to be confused with the kind of grass that grows on a lawn, which is called 'grasidi'. The Greeks use the word 'horta' interchangeably for the unwanted grasses and weeds that grow in fields, as well as for the various edible leafy greens that grow seasonally throughout the year. These usually grow wild, and are picked fresh for eating within the same week. In the summer, various kinds of horta grow uncultivated in our garden, and we never run out of them until the end of the season. We are growing some stamnagathi (spiny chicory) in our garden in front of the artichoke borders, and are hoping that it seeds to produce more plants next year. We also grow spinach and carrots, parsley and radish, with an unavoidable intercrop of stinging nettles. Although it grows wild, spiny chicory is in short supply and only grows in unspoilt, slighly remote areas of the province. The greens that are sold in shops are the cultivated varieties of the same wild species. They are not as tasty as those found in the wild, but beggars can't be choosers. Whether they are cultivated or found in the wild, spare a thought for the pickers; it's hard work bent over a field in the middle of winter. No wonder they are so expensive; I bought 2 kilos of horta last Thursday, at E7.30 a kilo - more expensive than meat, you might be wondering. Imagine how poor Ivy, who lives in Athens, feels when she pays E12 a kilo for her stamnagathi (spiny chicory)! Low income earners can hardly afford them. I prefer to buy them once every fortnight. As fresh greens, they can be eaten raw like a salad; once cooked, they can be kept in the fridge for a week, and they are eaten as a main meal or a warm salad. They are a very important part of our daily diet, given that we eat vegetables or salad with every main meal.

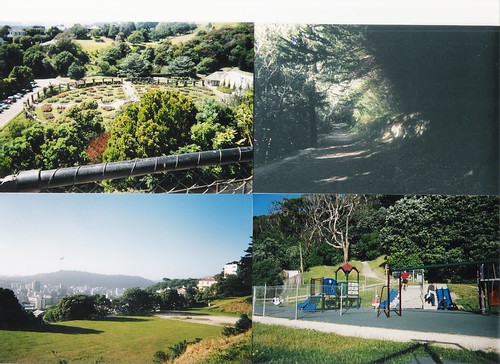

My absolute favorites are stamnagathi (spiny chicory; Cichorium spinosum), a low-lying shrub that grows amongst thorns in the hilly areas of Hania (foreground), often referred to spiny chicory in English. I also love maroulides, a kind of indigenous dandelion plant (background). My introduction to horta was in New Zealand when my immigrant Greek mother would take me and my sister to Pirie St Park, a few minutes walk away from where we lived in Mt Victoria, Wellington. We'd play on the swings, while she foraged among the low scrub and snapped the stems off bushes of amaranth, or dug up rooted grasses such as dandelion with a knife, which she gathered into a plastic supermarket carrier bag. Imagine how that would look in the days of political correctness: a 40-year-old woman brandishing a knife in a swing park! I had never tasted horta before I was 12; I found it too embarassing to even consider it. What would I tell my friends at Clyde Quay School when they asked me what we usually ate for tea (as the evening meal is called in NZ) at my house? "Grass? That's what sheep eat! Baa-baa! You have weeds for tea? Hey, everyone, Maria eats marijuana!"

My absolute favorites are stamnagathi (spiny chicory; Cichorium spinosum), a low-lying shrub that grows amongst thorns in the hilly areas of Hania (foreground), often referred to spiny chicory in English. I also love maroulides, a kind of indigenous dandelion plant (background). My introduction to horta was in New Zealand when my immigrant Greek mother would take me and my sister to Pirie St Park, a few minutes walk away from where we lived in Mt Victoria, Wellington. We'd play on the swings, while she foraged among the low scrub and snapped the stems off bushes of amaranth, or dug up rooted grasses such as dandelion with a knife, which she gathered into a plastic supermarket carrier bag. Imagine how that would look in the days of political correctness: a 40-year-old woman brandishing a knife in a swing park! I had never tasted horta before I was 12; I found it too embarassing to even consider it. What would I tell my friends at Clyde Quay School when they asked me what we usually ate for tea (as the evening meal is called in NZ) at my house? "Grass? That's what sheep eat! Baa-baa! You have weeds for tea? Hey, everyone, Maria eats marijuana!" This is just what some boys from Wellington College, a boy's high school close to our house, once jeered out to us (and then broke out into raucous laughter) when my mother (lady on the left in the photo) took me to their school grounds to collect some horta. It was after school hours on a fine day, probably a Monday, when my parents didn't open the fish shop (until the "kinezo", as my parents called him, opened up a takeaways shop 300 metres away from our own shop, cutting our profits and forcing us to become more competitive). I pretended that I was deaf, dumb, mute, some kind of alien, and I didn't understand what they were saying to us. Now that I think back on that day, we must have looked really queer holding a plastic bag full of roadside greens that had been removed from the carefully tended grounds of one of the most revered boys' schools in Wellington. My mother always used a blunt silver knife to prise the horta out of the ground if they were very well-rooted, another good reason for someone to stare at you wildly. The sad thing about this incident is that the boys weren't pale-faced Pakehas - I still hold an image of that day: they two of them were in school uniform, sitting on a high fence above some flower beds. They were wearing regulation grey shorts, so that their brown legs were highly visible. Maybe they were still in the school grounds for sports practice. They were Maori, and they had no idea that what these two grasscutters were doing was actually what some of their ancestors had been doing for many years before the white man came and 'taught' them to eat different food.

This is just what some boys from Wellington College, a boy's high school close to our house, once jeered out to us (and then broke out into raucous laughter) when my mother (lady on the left in the photo) took me to their school grounds to collect some horta. It was after school hours on a fine day, probably a Monday, when my parents didn't open the fish shop (until the "kinezo", as my parents called him, opened up a takeaways shop 300 metres away from our own shop, cutting our profits and forcing us to become more competitive). I pretended that I was deaf, dumb, mute, some kind of alien, and I didn't understand what they were saying to us. Now that I think back on that day, we must have looked really queer holding a plastic bag full of roadside greens that had been removed from the carefully tended grounds of one of the most revered boys' schools in Wellington. My mother always used a blunt silver knife to prise the horta out of the ground if they were very well-rooted, another good reason for someone to stare at you wildly. The sad thing about this incident is that the boys weren't pale-faced Pakehas - I still hold an image of that day: they two of them were in school uniform, sitting on a high fence above some flower beds. They were wearing regulation grey shorts, so that their brown legs were highly visible. Maybe they were still in the school grounds for sports practice. They were Maori, and they had no idea that what these two grasscutters were doing was actually what some of their ancestors had been doing for many years before the white man came and 'taught' them to eat different food.My mother probably got a tip-off from her sister about where to collect the greens; one of my aunt's neighbours seemed to know all the best places for collecting horta, but wouldn't tell anyone else, obviously to keep all the good places known to himself only. "I saw Pantelis coming out of his car with a bagful of horta - wonder where he picked them from..." But horta were everywhere: by the hill at the end of Elisabeth St, near the bowling greens at Pirie St, surrounding the Byrd Memorial at the Mt Victoria Lookout, the whole of Wellington was so green that everyone who owned a quarter-acre bungalow could pick enough horta straight from their own patch of garden. My aunt still manages to do this; rain has a definite advantage, something that is lacking in Crete.

Worse tidings awaited me when a teacher from the school explained to us that a particular plant called black nightshade was highly poisonous and we shouldn't touch it at all. "Oh, that," I said, "my mother picks and cooks it and we eat it." What did I say that for? The ahead-of-her-time, politically-correct, progressive-thinking teacher gave me a funny look, and said, "Oh, does she?" Wasn't that nice of her? When I went home that evening, I told my mother about what the teacher told us. "Only the berries are poisonous and we don't eat those," she told me, "and you always eat stifno together with vlita." The amount of stifno you eat with vlita should be in a smaller proportion to that of vlita, about 1:4 stifno:vlita.

Talking about grass-eaters in my youth was a definite no-no; the same applied to other 'foreign' foods, like snails (found those in the garden, too) and black olives (from the Italian grocer's close to the park). It was simply something you didn't talk about as a young child growing up in the NZ of the seventies. How different life is now, when any oddity concerning your cultural heritage is an aspect to be flaunted, with no shame attached. And if you can get a journalist to write an article about it, you'll get your fifteen minutes worth of fame.

At the time, I was too young and ignorant to understand the importance of leafy greens: the role they played in the good health of the rural poor, how they help to fight against diabetes and heart disease, their low calorie and high nutritious value. Unfortunately, the original eaters of these greens in NZ were also swayed away from their native diet with the arrival of the European, and they, too, forgot the important role of puha (as horta are known by the New Zealand Maori) in their daily diet. It does beg the question why my Greek immigrant parents went to such lengths to find the food they were used to eating in the poor Greek villages that they were brought up in, while the native-born of a country, where it rained half the week and there was never a shortage of foliage, had been tricked into forsaking their native diet, and had had it instilled in them to buy their food from shops. I am not advocating a method for reducing poverty levels by getting the poor to forage for their own food in public parks; if this was ever implemented, anyway, they would probably be charged a tax , something like a congestion charge, to compensate for injuries caused to living organisms. On my last visit to NZ, however, I noticed that puha (the Maori word for amaranth) was being sold as an upmarket salad vegetable, in small bunches, tied together like a posy. My mother's sister who still lives in Mt Victoria picks the same stuff from the comfort of her own home, right from her tiny patch of a garden, where pasrley, mint, dandelion and amaranth grow nearly all year round without being sown.

At the time, I was too young and ignorant to understand the importance of leafy greens: the role they played in the good health of the rural poor, how they help to fight against diabetes and heart disease, their low calorie and high nutritious value. Unfortunately, the original eaters of these greens in NZ were also swayed away from their native diet with the arrival of the European, and they, too, forgot the important role of puha (as horta are known by the New Zealand Maori) in their daily diet. It does beg the question why my Greek immigrant parents went to such lengths to find the food they were used to eating in the poor Greek villages that they were brought up in, while the native-born of a country, where it rained half the week and there was never a shortage of foliage, had been tricked into forsaking their native diet, and had had it instilled in them to buy their food from shops. I am not advocating a method for reducing poverty levels by getting the poor to forage for their own food in public parks; if this was ever implemented, anyway, they would probably be charged a tax , something like a congestion charge, to compensate for injuries caused to living organisms. On my last visit to NZ, however, I noticed that puha (the Maori word for amaranth) was being sold as an upmarket salad vegetable, in small bunches, tied together like a posy. My mother's sister who still lives in Mt Victoria picks the same stuff from the comfort of her own home, right from her tiny patch of a garden, where pasrley, mint, dandelion and amaranth grow nearly all year round without being sown. The main problem with freshly picked wild greens is that you don't know who (or what) was treading (or doing whatever else) on them before you picked them. So it's very, very important to wash and clean them well, whether they've been picked in the wild or bought from a store. Plug the sink and wash them in there, beating them about, draining the sink and filling it up again, until the water is not muddy and has a certain clarity you normally associate with water. You will use a lot of it in doing this job. This is not being wasteful; it should make you think about the less affluent, whose water supply is impure or non-existent. Count your blessings here. Once you've washed the horta well, remove the rotten leaves; they stick out a mile away by their brown colour, as opposed to the natural green of the horta. Trim the stems if they are too tough to eat, or contain woody parts. Dandelion roots will actually become very soft when boiled, and they are the most delicious part of the plant. Give the horta a final wash in the sink.

The main problem with freshly picked wild greens is that you don't know who (or what) was treading (or doing whatever else) on them before you picked them. So it's very, very important to wash and clean them well, whether they've been picked in the wild or bought from a store. Plug the sink and wash them in there, beating them about, draining the sink and filling it up again, until the water is not muddy and has a certain clarity you normally associate with water. You will use a lot of it in doing this job. This is not being wasteful; it should make you think about the less affluent, whose water supply is impure or non-existent. Count your blessings here. Once you've washed the horta well, remove the rotten leaves; they stick out a mile away by their brown colour, as opposed to the natural green of the horta. Trim the stems if they are too tough to eat, or contain woody parts. Dandelion roots will actually become very soft when boiled, and they are the most delicious part of the plant. Give the horta a final wash in the sink.At this point, you have to decide if you are going to eat them raw or cooked. Because they are a winter crop, we prefer to have them served hot. I believe that they could be used in the same way as spinach and vlita for kalitsounia and spanakopita, although I've never tried it (spinach being plentiful at this time of year). If you've decided to cook them, get your largest pot out of the cupboard and fill it with water which you've set to boil. Once the water starts bubbling, add enough washed horta to fill the pot to the top, and wait for them to shrink in size as they wilt in the heat of the water. Then add more horta, and turn them over using a ladle, or large slotted spoon to avoid burning yourself with the scalding water which may spill over the pot, so that the wilted greens are on top of the fresher ones. This is why we never add horta to a pot of cold water; it's also a waste of energy.

Once the pot is full, and it starts to boil, let the horta cook for about five minutes, and then drain away the water, and refill the pot with fresh water. Let the greens boil away again. I do this at least twice to remove all the impurities from the horta which weren't removed when I was cleaning them before cooking. It also removes the bitter taste of the greens, especially if they are cultivated and not grown in the wild. The water will have taken on a green colour, becoming lighter and more golden with every change of water. I left the horta boiling uncovered for an hour in their last change of water. This is a matter of taste. My family prefers them soft rather than crucnhy. In restaurants, they are served crunchier than in private homes. This is not just to skimp on cooking time and fuel consumption; in their less cooked form, they are bulkier, meaning that you can serve less of them on a plate. Coincidentally, restaurant owners also freeze parboiled (well-drained) individual servings of horta, and heat them up in boiling water when they are ordered by customers. I wouldn't do this myself, as horta are widely available in Crete throughout the year. I remember doing this once nearly 10 years ago when we had been allowed into a friend's field and told to dig up as many greens as we wanted to take away with us. We razed the field.

Once the pot is full, and it starts to boil, let the horta cook for about five minutes, and then drain away the water, and refill the pot with fresh water. Let the greens boil away again. I do this at least twice to remove all the impurities from the horta which weren't removed when I was cleaning them before cooking. It also removes the bitter taste of the greens, especially if they are cultivated and not grown in the wild. The water will have taken on a green colour, becoming lighter and more golden with every change of water. I left the horta boiling uncovered for an hour in their last change of water. This is a matter of taste. My family prefers them soft rather than crucnhy. In restaurants, they are served crunchier than in private homes. This is not just to skimp on cooking time and fuel consumption; in their less cooked form, they are bulkier, meaning that you can serve less of them on a plate. Coincidentally, restaurant owners also freeze parboiled (well-drained) individual servings of horta, and heat them up in boiling water when they are ordered by customers. I wouldn't do this myself, as horta are widely available in Crete throughout the year. I remember doing this once nearly 10 years ago when we had been allowed into a friend's field and told to dig up as many greens as we wanted to take away with us. We razed the field. The final product is served with the traditional Greek dressing: olive oil, salt and lemon juice. If they are not being served as a salad, they can be the main course, served with boiled potatoes, boiled eggs, gruyere or feta, and of course, thick slices of sourdough bread to mop up the liquid. We're having it today with some leftover soutzoukakia from yesterday's meal.

The final product is served with the traditional Greek dressing: olive oil, salt and lemon juice. If they are not being served as a salad, they can be the main course, served with boiled potatoes, boiled eggs, gruyere or feta, and of course, thick slices of sourdough bread to mop up the liquid. We're having it today with some leftover soutzoukakia from yesterday's meal.This post is dedicated to my late mother, Zambia.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

MORE WILD GREENS RECIPES:

Kalitsounia fried

Kalitsounia in the oven

Marathopites

Spiral pie

Hortopita (spanakopita)

Horta in summer

Sorrel

Swiss chard (silverbeet)

Eggs with mustard greens

Mountain tea

Octopus stew

Wild asparagus

MORE SALADS:

Cabbage salad

Lettuce salad

Salad advice

Greek village salad

Cretan salad

Summer horta

Beetroot salad

See also:

A day in the field

The rape of the countryside

A summer garden

A winter garden

An autumn garden

Table olives

I absolutely love wild horta of all kinds and gather them both in Alaska and Greece. In Greece, kafkalithra is my favorite - don't know if you have it in Crete. Wild horta make the best pita, in my opinion, especially if you have a mixture of different greens, some sweeter and others more bitter. I make hortopita whenever I can. Horta is also quite tasty in kalitsounia.

ReplyDeleteThis is a really great post, and I can visualize the entire scene with you and your mom in NZ. Great writing!

We love horta, we love them in pies, we love them as salad, we love them in kalitsounia.

ReplyDeleteI have already written about kalitsounia, summer and winter horta, and spanakopita, which is actually a kind of hortopita anyway

They are never missing from our deep freeze – try my post on ROAST CHICKEN to see why (more crazy Greek-NZ tales there too).

We also have kafkalithres in Crete, but because we have such an abundance of horta, they are not the most popular greens here.

Deep freezes are a miracle invention.

ReplyDeleteDo you realise you can freeze cleaned, washed, parboiled, drained horta in small batches? This is done by restaurant owners for the expensive types of horta, such as stamnagathi and askrolimbous (a rooty type). I've had it before in a taverna, and it tasted almost fresh.

ReplyDeleteYou mention the stinging nettle- did you know that it's edible too? It's very nutritious! It doesn't grow where I live, so I've never eaten it, but someday...

ReplyDeleteI loved reading here about your mother foraging. It was beautiful.

Oh, and I have a question: you seem to cook the greens for a loooooong time. Don't you worry about the nutrition being leached out of them with the water changes? I use a big pot for my greens, but only a small amount of water, & cook until tender- usually 10-20 minutes. If there's any water left to drain, I drink it!

Hi, Maria:

ReplyDeleteMy sister found your blog and sent me the link. Our yia yia and papou are from Kambi as well, and my yia yia's mother was named Zambia Gavrilakis. She married Mihali Pappadakis. My yia yia Maria married Vasilios Dimotakis (his mother was Elpitha Kourakis). I'm sure somehow we're cousins, with a village that teeny. My grandparents moved to the US in the late 1910s, and settled in central California.

Anyway -- HORTA! My whole family loves it, including my two kids (8 & 10). People can't believe the kids eat boiled greens. We were on a family trip to Chania in April and ate dinner at Apostolakis near the Agora, and had the thistley horta that you're talking about. It was our first time, and everyone LOVED it! The stems are to die for! I wish we could get it here at home, but haven't had any luck.

Love your blog!

coming from that kind of tiny village, we probably are cousins!

ReplyDeleteHello,

ReplyDeleteI'm looking long stamnagathi (Cichorium spinosum) spiny chicory, with roots or seed.

It is to grow in the south of france.

Who can send me several plants.

I offer good prices for shipping by mail in France.

Proposal to me by mail.

My E-mail: gitesdusud@gmail.com

Την καυκαλίθρα στην Κρήτη, την λένε μυρώνι...

ReplyDeleteΑυτό μόνο...

καλημέρα απο ΝΖ...

Poli omorpho post Maria!

ReplyDeleteBTW, In Eastern and Central Crete kafkalithra is eaten raw in salads or browned. In Cretan dialect its name is myridousa or mouskoulida. Its bot. name is Tordylium apulum, while myroni is Scandix (cretan: ahatzikas)