When I was last in London, my cousin asked me if I wanted to have a meal at a gourmet hamburger restaurant. I never knew those words could ever be collocated: fine food, fast-food style, as a sit-down knife and fork meal? I was even more surprised to hear that it was inspired by New Zealanders; more Kiwi ingenuity (pronounced 'kayway enge-new-iri') I decided to pass on it, as I preferred to stuff myself on old-fashioned English cakes and cheap Asian food, which is still a novelty in Hania, although we now have two all-year round not-so-cheap Chinese diners serving the province.

Where does a BLT fit into the Mediterranean cuisine? My attempt to mediterraneanise it might be viewed as a desperate move to find something to cook that I haven't already presented in my blog (sorry, I forgot to celebrate my first bloggoversary), a sign of my rotationalised cuisine, with recipes based on local produce and regional recipes. Or it could be a way to say "I'm bored of cooking and eating the same food." In a culture where my female forbears followed a cyclical repertoire of culinary tradition - something like: Monday, beans; Tuesday, mince; Wednesday, horta; Thursday, fish; Friday, rice or pasta; Saturday, leftovers, culminating on Sunday with the traditional meat roast - which I am pretty much imitating, a moment of truth will emerge: I am cooking the same recipes over and over again, variation depending on the season, which explains why I don't present many new recipes any more. I've shown my readers pretty much all that we cook on a regular basis in our own house, recipes which are used and re-used for health reasons, for simple cooking, or because they have become a personal favorite in our household, although there are countless Greek dishes I have not presented; as one of my readers pointed out, why haven't I cooked youvarlakia yet?

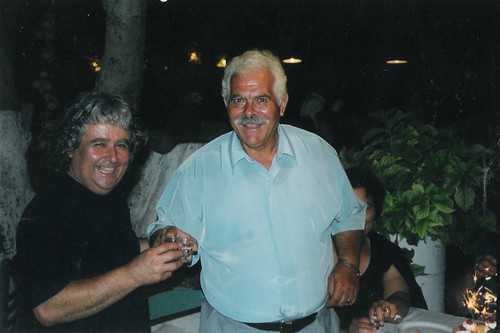

Am I bastardising Greek cuisine by passing off a BLT as a Mediterranean variety of sandwich? The ingredients I've used have all been produced locally. Some have even come from my own garden. Is a BLT just bacon, lettuce and tomato in a bread roll? Isn't it a kind of snack, and not a proper meal, despite the fact that BLT probably constitutes most Americans' lunch on a daily basis? If we're having junk food, we usually make it ourselves, which makes it less junky. Pizza and souvlaki are regular favorites of ours, while hamburgers with bifteki are a regular lunchbox filler when the children are at school. We all recognise a good burger when we see one. Darius has invented a sandwich-type burger that suits me to the tee: grown-up BLT. Here's how I remade his recipe to suit Mediterranean island tastes, replacing ingredients not available in Smallsville with ingredients based on the local produce in our garden, together with food that we now take for granted as a part of the realm of international cuisine.

Step 2 was much easier: oven-cook strips of bacon and glaze it with honey. Bacon and honey-glazed meat aren't really part of the Cretan cuisine. Bacon resembles the Italian pancetta, but if you go to a Greek supermarket, beware: what the Greeks call pancetta is something completely different. Pancetta in Greece refers to a fatty cut of pork which looks like a pork chop, but it is much cheaper (due to the excess fat on it). Bacon is made in Greece from locally-bred pigs, although I hardly use it in our daily cuisine (usually as an addition to a quick pasta sauce). But there is plenty of it in the stores, especially at this time of year when tourists are demanding it, to make BLTs in their self-catering apartments. It is not sold by butchers (in Greece, they also sell sausages and other deli items containing meat), which clearly marks it out as a 'processed' or 'foreign' meat cut rather than a local product. As for honey, we go through a kilo of locally produced honey every month: thyme-flavoured, runny clear liquid which we buy from my beekeeper cousin, who's been refilling our recycled honey jars for the last six years.

Step 3 was my favorite: fried green tomatoes (I loved that movie). After making over 20 kilos of tomato sauce for winter, I was more than happy to use the tomatos before they ripened. They are not really a loss, as I think we'll be eating garden fresh tomatos until November, when the weather actually starts getting cold. Saying this, my thoughts go out to Keewee, whose tomatoes are probably going to stay green in her garden, because Washington weather will not let them ripen much more...

Step 4 involves toasting ciabatta rolls. In Hania these days, we can get a whole range of fresh bread rolls of every size, shape and colour. My family's personal favorite bakery is the MALEME bakery which distributes their delicious rolls, hamburger buns and baguette breads at all the INKA supermarkets. Pity they don't have a web page, which isn't surprising, given the state of the use of the internet in Greece. MALEME bakery uses yeastless sourdough. The loaves and rolls are made from white, brown or a mixture of flours. They are also baked with cheese or olives to make the buns more savoury, and they are shaped into loaves, rolls, burger buns, baguettes, mini-buns and ciabattas. I chose the classic white roll today, and rolled it around an oiled frying pan, just till it browned and soaked up the oil.

Lettuce is widely available throughout the year in Crete, but it's not a particular favorite of ours in summer, given the abundance of vlita for a hot salad, and tomatos for a cold salad. Today, I found some lollo at the supermarket, curly lettuce, a novelty for us in Crete, as the main lettuce grown on the island is Cos (Romaine) lettuce. Small lollo leaves make a perfect substitute for lettuce in the tight space that a filling takes up in a sandwich. As this BLT is going to be open gourmet-style, I spread some mizithra cheese on the roll (making the mayonnaise redundant - Darius used a slice of the all-American muenster) and a few black olives on the plate for a truly magnificent gourmet sandwich served under a Mediterranean sky.

BLT is probably something that can easily be copied from one cuisine to another. I challenge my Greek food bloggers, enthusiasts and readers alike to try recreating an authentic recipe from a culture completely foreign to the Greek one, using Greek-inspired ingredients, and vice versa. Globalisation does not have to mean that we eat, for example, Chinese sweet-sour pork in Greece only at Chinese restaurants, or that we need to buy a prepared sauce in a sachet or jar to make it at home. Let's look at our local products and try creating a meal that can equally be called Greek as much as it is international.

Thanks, Darius, for a wonderful snack, and a new way to view my local products, especially the tomatoes, which seem to be getting the better of me these days.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.