Every year my children's primary school organises a school trip for the whole school. It's usually based on entertainment value (eg a trip to

Paleohora for the sun, sea and sand, with a taverna and cafe thrown in), but this year, thanks largely to a new headmaster, the outing took on a more educational approach. We visited

Knossos, a small village located 1 kilometre away from the hospital where my daughter spent the first four weeks of her life as a premature baby, just out of

Iraklio (two hours away from

Hania), the largest town in Crete, or should I say, the

fifth largest town in the whole of Greece.

The ominous black clouds above the school building and the few drops of rain that fell on our heads did not deter us in our excitement over the annual school trip. Greek schoolchildren lining up for assembly before boarding the buses; this village school has a small roll.

Kindergarten and 1st graders had to be accompanied by a parent or guardian, but this isn't the reason I went along on the trip. There would have to be a very good reason for me to turn down a visit to the

first civilisation known to man in the whole of Europe. Knossos, headed by

King Minos, existed 12 centuries before the

Acropolis; the legacy left behind by

Pericles does not toll as loudly as that of King Minos.

The word 'Knossos' brings to mind not a modern Cretan village, but the remains of an organised ancient city centred around a palace state, which was flourishing 4000 years ago, with colourful frescoes on the walls, columns made from cypress trees, storage cellars for oil and wine, and

even flushing toilets for the royalty.

The palatial site at Knossos was rebuilt many times over the centuries after being destroyed by fire and earthquakes, and continued to be

used for more than 500 years (1900-1350 BC), an awesome fact if compared with the modern trend to knock down buildings that seem useless to us, another example of our throwaway culture.

*** *** ***

Because the actual journey was a long one, we had our first pit-stop (supposedly a 10-minute toilet stop) at a coach station. This gave me just enough time to witness the horrors of

the junk food culture that has overtaken the land that gave us the Mediterranean diet. Of course, you can't expect anything other than junk food and exorbitant prices in such an outlet. Most of the older children were unaccompanied and hence were given an allowance to cover such expenses, just like my children will be given some time in the future, and they will probably make junky choices like the ones the other kids made. There is little likelihood that my 'organically cooked' children will make sound food choices when they are given the opportunity to make up their own mind about what to buy from such refreshment kiosks.

The coach station was a good opportunity to watch how some parents try to kill their children. The (obese) mother in the right is helping her (fat) child to have just enough fizzy drink to make him feel queasy when he gets back on the bus (and vomit along the windy road to Iraklio, I suppose), while his (fat) brother ponders over how he will manage to eat his way through a whole chocolate bar, a large ham and cheese sandwich and a fizzy drink before he gets back on the bus; the driver specifically stated: "No eating or drinking except water."

Needless to say, I bought along some home-made cake and two bottles of water. We sat communally with other parents and children, watching them all devouring crap. My daughter threw a tantrum. "Cake, cake, always cake, can't we just

buy something?" She began to cry in that way that children do, when they think there is some hope that their parents will become embarrassed and then succumb to their whims and fancies.

Life sucks when your mother's in charge.

We had all had a decent breakfast before leaving the house. The bus was air-conditioned, and we were seated for over two hours. How much energy does one expend under such conditions? And where the hell is the Mediterranean diet anyway, and

the traditional Greek mother who'd spent the previous night cooking up a whole picnic to feed an army?

*** *** ***

The last stretch to Iraklio (Knossos lies 3 kilometres out of the centre of the town) is on a curvy hilly road. It isn't the most scenic route, but you get an idea of how different Iraklio is to Hania, and how unlike an island Crete actually is. Iraklio is overpopulated for the surface area it covers. It is bordered by the sea in the north, while high mountains border the prerimeter of the city to the south. Apartment blocks have even been built in the midst of mountain forests (possibly not legally); Iraklio lacks residential space. Despite its random building projects which give it a haphazard Athenian neighbourhood look with tall aesthetically-lacking apartment blocks, Iraklio is an important centre in Crete and has a lot of clout politically and economically.

As you enter or drive through Iraklio, you can't help wondering if you've lost your way and gone to Athens instead; it lacks any of the charms associated with a Greek island

As you enter or drive through Iraklio, you can't help wondering if you've lost your way and gone to Athens instead; it lacks any of the charms associated with a Greek island.

Hania may be a more beautiful part of the island, but Iraklio is more organised, more judicious and more hard-working than the other prefectures of Crete (personal experience). There is a certain amount of

friendly rivlary felt between the Haniotes and the Irakliotes, and not without reason (

Hania lost its capital city status to Iraklio in 1971), but Iraklio is still the city and prefecture that attracts people from all over the country, being located right in the middle of the northern coastline of the island. It's been the largest urban centre in Crete since Minoan times.

If you know what there is to see, you will look out for Mount Youktas, where the leader of the Greek gods is buried (you can see his face in the outline of the moutain). Zeus was a Cretan, born either in or in Dikteon Andron in the Lassithi plateau, who ruled in Mount Olympus, and died in Crete, despite being immortal. After a 2 1/2 hour bus trip, we found ourselves outside Knossos at the commercial part of the site, where the cafes and souvenir shops are located.

Parents were given a choice of accompanying their children for half the price of the full 6-euro ticket (children on school trips enter for free with their teachers), or wait outside the entrance to the site until the children finished the (

guided!) tour. It is embarrassing to confess that most of them preferred to remain as educated as they were before they left their homes that day ("

I came here on a school trip when I was a kid, I've already seen this before!").

Some parents headed off to the nearest cafe; I picked up the official guidebook from the site (6 euro, available in many foreign languages). The souvenirs are good value if you are into ornamental reproductions. Our mellifluous guide carried a blue umbrella high above her head as we walked with her; our school was not the only visiting Knossos on that day!

Some parents headed off to the nearest cafe; I picked up the official guidebook from the site (6 euro, available in many foreign languages). The souvenirs are good value if you are into ornamental reproductions. Our mellifluous guide carried a blue umbrella high above her head as we walked with her; our school was not the only visiting Knossos on that day! They decided not to enter the site (which would have cost them only 3 euro); they probably amused themselves instead by hanging out at the cafe bars that were dotted around the area, drinking

frappe coffee, eating more junk food, and buying some more sugary drinks for their kids just before they began their tour (the teachers kept reminding them that they were on a no-food-allowed site).

With our water, hats, sunscreen and sunglasses (Knossos is very exposed to the burning sun), we entered the ruins of the palace of Knossos, which itself is surrounded by the remains of the houses of Minos’ subjects, who lived outside and around the palace grounds, which is why taking

just one little step in the area means that you are walking on some more of the hidden ancient antiquities that the world is simply waiting to be brought to light...

*** *** ***

The earliest evidence of human activity in Crete comes from

6100 BC, in what is known as the Pre-Pottery period. No findings from the Paleolithic age (paleo - old; lithic - stone; the Old Stone Age) have been determined yet in Crete (although they exist in other parts of Greece), but this could happen in the future; the Paleolithic Y-haplogroup heritage predominates in the gene pool, as found in a Cretan highland plateau. Remains of wheat, barley and lentils, as well as the bones of domesticated animals (goats, sheep and pigs) indicate that this group of people were not nomadic. Between

5700-2800 BC during the

Neolithic Age (neo - new; lithic - stone), people were living both in both caves and houses constructed of rough clay bricks, stone and wood . The population of Crete at this time was composed of

different nationalities,

most likely from the west rather than the east Mediterranean.

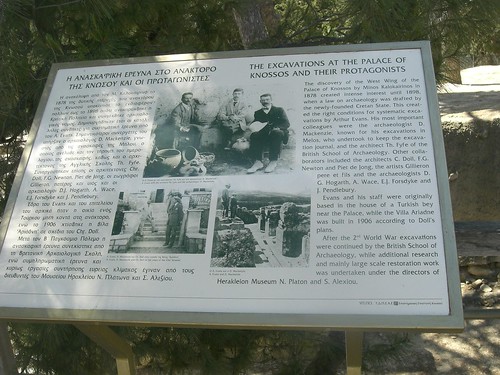

For many years, the palace at Knossos remained under the ground, most likely due to

a volcanic eruption in Santorini, which created such a large tsunami that it covered the coastal areas of Crete. But stories of its legendary status and the ruling King Minos remained; even in those dark days, villagers who dug up their land for a range of purposes found various bits and pieces of items dating back to the days of antiquity. In 1878,

a young Iraklioti (ie he came from the city of Iraklio), appropriately named Minos (

even the name of the king lived on!) unearthed a part of the storage areas of the palace...

... but the Ottoman (Turkish) rulers of

Crete of the time didn't let him to do any further work in the area.

Heinrich Schliemann (who had already helped unearth the treasures of

Troy and

Mycenae) heard about Minos' lucky finds, but wasn't able to raise the funds needed to buy the site from the Turkish landowners, leaving the site exposed to

Elginism, which thankfully did not happen.

In 1900, mainly due to luck, just a few years after the Ottomans were ousted from their official ruling role in Crete, the site of Knossos fell in the hands of the kindly

Englishman Arthur Evans, who the town of Iraklio now thanks for helping unearth the treasures of Knossos with a well-deserved statue of Sir Arthur at the entrance of the ancient site. He excavated most of what we see nowadays of

Knossos (and

controversially rebuilt some parts of the destroyed palace) and gave the name 'Minoan' to this time period, which lasted over 1500 years (2600-1000 BC).

*** *** ***

It is difficult not to feel a sense of awe when you find yourself in the heart of the Mediterranean under its clear blue sunny sky at one of the most ancient sites of

Europe, in the company of a beautiful guide who began relating stories to us about King Minos and his palace in a sing-song fairy-tale fashion.

The Minoans were surrounded by beautiful scenery - low undulating hills, the bright green foliage of the trees and the clear blue sky.

The Minoans were surrounded by beautiful scenery - low undulating hills, the bright green foliage of the trees and the clear blue sky.This tour was intended for the lower primary school grades, which made those stories sound even more thrilling; the adults simply have to read between the lines as they hear about the antics of the Greek gods to turn this amazing story into one of sexual fantasy and intrigue:

"One day, Zeus spotted Europe as she was playing in the fields, and he thought she was the most beautiful girl among all her frolicking friends. So he transformed himself into a gentle bull and lured her away from her native land, taking her to the shores of Crete, Zeus' birthplace (and where Zeus is believed to have been laid to rest) where he finally revealed himself.

The Greek 2-euro coin depicts Europa riding on a bull (Zeus), making her way to Crete.

She had three children with him, one of which was Minos, who became a King and married Pasiphae; the palace of Knossos was built for his family and servants by a clever man called Daidalus.

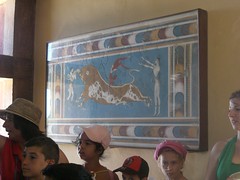

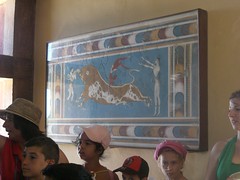

The reconstructed frescoes give us an idea of what the Minoans looked like 3000 years ago: they were short (in our terms), with a tanned skin, dark eyes and dark hair. Males (always depicted in red) and females (always painted white) had similar hairstyles and clothing. The symbol of the bull features throughout their culture: the birth of King Minos, the Minotaur, and the Bull Games (Ταυροκαθάψια - tavrokathapsia).

Minos was such a powerful king that when Aegeus, king of Athens, killed Minos' son Androgeus, Minos had the Athenians send him the 7 most handsome boys and the 7 most beautiful girls from the mainland, whom he threw into the darkness of his labyrinthian palace which had many rooms and was difficult to get out of once you got in. These young people got lost in the maze, where they were eventually eaten up by the hungry Minotaur, a half-bull half-human creature (the creation of Minos' wife Pasiphae, after she had an affair with - you guessed it - a bull) who lived in the centre of the labyrinth.

The myriads of rooms found side-by-side, one on top of another, remind you of a labyrinth.

The myriads of rooms found side-by-side, one on top of another, remind you of a labyrinth.

The Minotaur was eventually killed off by one of those young people, Theseus, who was also able to find his way out of the palace with the help of Minos' daughter Ariadne, who gave him a ball of string which he tied to the entrance of the labyrinth that showed him the way out as he twined it back into a ball.

"Minos was a bit more than a tad angry when he realised what had happened, especially since Ariadne took off with Theseus to Athens. Theseus was having such a good time celebrating his many successes in Crete that he forgot to change the sails on his boat, so that when his father sighted his son's ship bearing black instead of white sails, he thought that Theseus was dead, so he threw himself into the sea and drowned (which is how the Aegean Sea got its name).

Undoubtedly, these images are the most famous from Knossos, known all over the world: top - the Queen's room; left - a reconstruction of part of the palace; right - the throne room; bottom - close up of the reconstruction.

Minos knew that Ariadne must have got help from someone cleverer than herself, so as to be able to help Theseus; he laid the blame on the designer of the palace, Daidalus, who realised that if he wanted to escape the palace and Minos' scrutiny, he would have to find a route other than by land or sea, as Minos controlled these two pathways. He chose to fly out with his son, Icarus, with the help of a set of wings he made for each of them using bird feathers that fell in the palace grounds and beeswax.

The Minoan civilisation is the first known literate civilisation in Europe. The Minoans were very advanced for their times: they had invented intricate sewerage systems that even included flushing toilets. This amphitheatre pre-dates Hellenistic ones: they were square and people always stood up. Maybe the local council convened here and discussed things like smelly sewerage... Interestingly, no weapons have been found at the site, which leads one to believe that the Minoans were a peaceful race, but this also left them vulnerable to attacks.

The Minoan civilisation is the first known literate civilisation in Europe. The Minoans were very advanced for their times: they had invented intricate sewerage systems that even included flushing toilets. This amphitheatre pre-dates Hellenistic ones: they were square and people always stood up. Maybe the local council convened here and discussed things like smelly sewerage... Interestingly, no weapons have been found at the site, which leads one to believe that the Minoans were a peaceful race, but this also left them vulnerable to attacks.

He warned Icarus not to fly too close to the sun, because the wax would melt and the feathers would come loose, and he'd lose his wings and fall to his death. But Icarus did what all children even in modern times do - he disobeyed his father, flew too close to the sun, and eventually lost his wings. The sea where he fell was named after him (Ikarios), from which the name of the nearby island is also derived (Ikaria).

"His father survived and ended up in Sicily, where Minos decided to hunt him down. As he sat at the Sicilian King Kokalus' palace, Minos asked him to solve a riddle for him. King Kokalus searched out Daidalus to tell him the answer (there's always a clever person behind a successful one) to the riddle, which gave away the whereabouts of Daidalus. Minos then demanded that Kokalus release Daidalus to him. Kokalus agreed, but while Minos was having a bath just before leaving Sicily with Daidalus, he was killed by one of Kokalus' daughters."And that was the end of King Minos, but not his splendid palace and the civilisation that he created. The Minoan civilization became vulnerable to attacks by mainland Greeks after 1450 BC, which was approximately the time of a volcanic eruption in Santorini that created a tidal wave that reached Crete and possibl covered Knossos with ash. The Minoans were conquered by the

Mycenaeans who gave Crete the many Peloponesian-sounding placenames that are still in use today, but after the fall of

Troy, the Mycenaeans were also conquered in

Crete by the powerful and destructive Hellenistic

Dorians.

Crete's two main export products: tourism and agricultural products, mainly olive oil, usually found side-by-side all over the island.

Crete's two main export products: tourism and agricultural products, mainly olive oil, usually found side-by-side all over the island.That's when Crete started to take on a Greek look; the

Eteocretans (the real Cretans, as Homer called the original Cretans before the invasion of conquerors) eventually turned into Greeks, so that,

by the ninth century BC, Crete had become totally Greek.

*** *** ***

After the guided tour which lasted 1 1/2 hours, we left the palace grounds, and entered the fast modern world that we had left behind just before we started our journey. We were all a little thirsty, so I looked round the commercial part of the

Knossos site to buy some cold juices. There was a very upmarket looking café located across from the entrance to the site, with mounds of oranges lining its boundary walls.

I ordered two cups of freshly squeezed orange juice, and nearly fainted when I heard the price: 4 euro a cup. I felt relieved that

we haven’t been selling our orange crops for the last two years (

due to the low prices offered to producers of agricultural products and the difficulty of finding a wholesaler willing to organize the labour), because Iraklio imports from our region – it is not an orange-producing area; Iraklio is known for its olive oil and grape wine. At least I wasn’t paying to drink my own product (although it

was absolutely delicious and perfectly refreshing).

My kids ate all the chips but left the souvlaki; I couldn't blame them. I succumbed to letting them have one ice-cream for the day.

My kids ate all the chips but left the souvlaki; I couldn't blame them. I succumbed to letting them have one ice-cream for the day.

We were then taken to our lunch spot, a children’s campsite called

The Land of the Lotus Eaters. The meals provided to the children were an absolute abomination – two dry souvlakia (kebabs on sticks) with a blob of yogurt, and a double serving of McDonalds-style pre-cut pre-fried French fries.

At least they were kept active before and after the meal. Hersonissos is in the distance, a few kilometres out of Iraklio city.

At least they were kept active before and after the meal. Hersonissos is in the distance, a few kilometres out of Iraklio city.

None of the children chose the healthier option of

youvetsi which was cooked to perfection and very tasty. Ice-creams and fizzy drinks were provided at a cost, and there’s no need to tell you that everyone (except us) was downing them by the dozen. What the Eteocretans or the Minoans would have thought of us if they were watching us at that moment remains a mystery. A year ago, I was bragging, boasting and pumping my head off that the

Mediterranean diet is alive and well and living in my children's school; a year on, it seems that it's almost dead and buried, living only as a fading memory.

This post is dedicated to Laurene, who knows more than I do about Knossos.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

.

.