Dear Ms Verivaki,

I must congratulate you on your magnificent prose and excellent cooking skills. I am a regular follower of your Hania blogs (I read them both every day), and there has never been a moment that I have been disappointed by the food you present and the stories you write. I have fond memories of spending summers in my youth in Crete, and I feel as though I am right there with you when you describe village life, the beach, the weather, and daily life in that splendid Mediterranean town where you live.

Over the past year that I have been following your blog, I notice you have been cooking everything the way my dearly departed grandmother cooked (she was from Kambi); the same meals, the same ingredients, the same method. Your family must revere you for the feasts you conjure up in your kitchen. The photos seem to jump out of the screen, screaming "That's my grandmama!" to me.

There is one recipe that I haven't yet seen on your blog, and that's youvarlakia. It's my favorite Greek dish, the one that my mother makes for me and sends it from California via courier to my apartment in Connecticut where I'm studying IT, in a tupperware container which she has frozen. When I receive it, I simply warm it up in the microwave and eat it on the same night that I received the packet, saving one serving for the next day. It tastes so good, and it always makes me feel homesick.

Here is my mom's yourvalakia recipe. It took me a few times making it before I turned out a batch that I was even satisfied with. In my mind, my mom's yourvalakia are always smaller and lighter than mine, and the avgolemono is always fluffier and more nicely balanced in flavor, but I continue to practice, and some day I hope that it'll be good enough that I can serve it to my mom and she'll be proud of it.

I thought that it would eventually turn up in your recipe list, but it's been over a year, and I understand that you cook according to a strict cyclical repertoire of recipes. Maybe your family doesn't like youvarlakia? Well, all people are different, aren't they?

I have never felt closer to my second home than through your stories. I'm looking forward to being comforted by more of them this winter.

Your loyal reader...

*** *** ***

.

Kambi, 1919

Nikolas had heard the word 'Ameriki' mentioned many times in the village. Ameriki was the land of a poor man's wildest dream, something akin to utopia, where everyone is happy, employed and rich, like his brother, who sent one single postcard to his family since he left Kambi.

When Nikolas' older brother Grigori returned to the village from Ameriki, he had enough money on him to buy 90 acres of land in the village, and live happily ever after. After working in the restaurant trade for five years in New York, being the patriot that he was, Grigori decided to return to the mother country to buy the land his family could not afford to give him and to complete his Greek military service, at a time when Greece was under attack from an enemy.

"In Ameriki, people are prepared to fight for their freedom. How can I stand and watch when my country is in danger?" he replied to his family when they pleaded with him not to leave so soon after his arrival. His betrothal to a blooming village girl arranged (as befitted his financial position), he had no sooner invested his money in buying land than he left again, this time to Thesaloniki where his knowledge of English earned him the rank of officer. He managed to survive the Battle of Skra, only to die from malaria two months before the end of the campaign, having never set foot on the land that he had worked five years on foreign soil to buy. It was shared unevenly among his siblings: his four sisters received a large share each as a dowry, making them attractively eligible for marriage, while Grigori's brother ended up with the remainder, a mere pittance of the original amount.

Nikolas received 10 acres of the land that had been bought with his brother's money from Ameriki, along with the beautiful bride his brother never married. He married her out of pity; even though her engagement did not constitute a marriage (there was no marriage to consummate in the first place), she would have a hard time finding another husband after being betrothed once already. Word would have spread that she was engaged to be married; her fate had already been decided. Who knows when the next offer would come? Nikolas also felt that she had partly inherited his brother's fortune, so that she deserved to be in on his good fortune.

Aggeliki, for all her outward qualities, was not the most useful woman around the house. She had been raised in the 'mimou aptou' way, as if her beauty did not permit her to cook, wash and clean the way a less attractive woman might conduct herself with respect to these duties, lest by applying herself to such tasks, her beauty may deteriorate, fade away, disappear, as if age could never play a part in this demeaning process, and it was all to do with how often one's hands touched the soil on the ground or how much sunlight shone on a woman's face.

Nikolas' land was fruitful, especially once he had cleared most of it from the thyme and dictamo bushes, after which he set about planting it with olive trees. He hunted hares and wild birds, plentiful in his own fields, but the cook was wonting in culinary skills; the rumour spread all over the village, with its population of 500, that Aggeliki was a hopeless cook. Nikolas didn't know who to feel sorry for more: himself for earning such fate, or the oven-charred or water-sodden carcasses that came out of the kitchen, sometimes sporting their fur or plumage. When he sat at the kafeneio with other men from the village, and listened to their chatter about how their own wives conducted themselves at home, his gut tightened.

"Give her time, Nikola, you're not even into a year of married life," the others would comfort him. But he neglected to tell them that Aggeliki entered the marriage in this way right from the start, and that his clothing was now almost ragged and Aggeliki showed no sign of replacing them for him before they had become tatters. He felt that the land - and possibly Angela's inviting appearance - had cursed him into the misfortune of a loveless marriage.

*** *** ***

When Aggeliki became engaged to Grigori, she had hopes of leaving the village for good. She knew that Grigori had made a lot of money, but she didn't realise that he had invested it in the mountainous territory that made up the village of Kambi. She expected that, once he had finished his military duty, he would move to lower ground - as most villagers who prospered did - and build a suitable dwelling for them to live in. After all, this is what he must have been accustomed to living in in Ameriki; everyone there apparently lived in fully furnished houses and had their clothes made for them by tailors and seamstresses. They did not need to shear sheep, spin yarn, or weave cloth on the argalio, which would eventually be turned into bedsheets and men's shirts; like cooking, sewing was not Aggeliki's forte. So it was to her greatest disappointment that Grigori did not return from Thesaloniki. She knew what fate had in store for her.

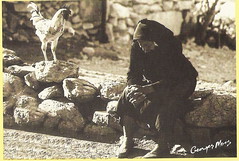

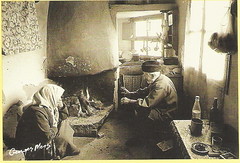

(Crete in the 1960s, four decades after Aggeliki and Nikolas emigrated; the photos come from CRETE 1960, by John Donat, Crete University Press)

Aggeliki had not wanted to marry her fiance's brother, but there was no question of that now that Grigori was dead. Had she been married to Grigori before he had left for Thesaloniki, she would have inherited his land, a mixed blessing if ever there was one. She would have become a rich woman, highly ineligible for marriage; what man in the village would have been able to match her wealth? As it was, she suffered the cruel fate of being labelled a widow after Grigori's death anyway, even though she had never married; such was the nature of life in the impenetrable snow-capped mountains of Kambi, at the foothills of the Lefka Ori.

She looked around the house Grigori had built in roughshod style a short while before they were married: two simple stone-built rooms with openings for windows, blocked by wooden shutters to stop the winter cold from entering. There was an outhouse a little way from the house and an earth oven built next to one of them rooms. This was not the Ameriki she had dreamed of, nor was it the town of Hania that she had hoped to move to after her marriage. It was true that she had never known better than the village life she was born into, but no one could stop her from dreaming, which is what she did most of the day when Nikolas was away, clearing scrubland, planting olive trees, hunting hares and grazing sheep.

*** *** ***

Kambi, 1921

Nikolas was sitting at the kafeneio. He usually sat on his own these days, as he had little to share with the locals. It was almost three years since he married Aggeliki and still no children. He had by now grown accustomed to the way the kafeneio chatter died down when he entered the shop, and the compassionate smiles of the other men sitting in groups around the tables. He picked up one of the newspapers that had been left on the fireplace, to be used for kindling a flame. Although he had not finished primary school, his reading was at a reasonable level. He did not write anything apart from his name; there was no one to write to, in any case, and no one interested in reading anything that he wrote.

He had not grown tired of working the village land. What tired him most of all - and he seemed to have aged a decade since his wedding day - was that he was working with no future in mind. So what if he had thousands of olive trees; so what if his coffers were filled with olive oil. There was no one to eat it, and no one to sell it to; people were too poor in the village to buy more as their own stocks ran out, so they simply used it more sparingly. The economy of the country was still engaged in a new war effort; there was no interest in trading olive oil. So much effort for very little reward; produce-rich but lacking currency.

Every morning started off the same, as every evening finished. Routine after routine, with very little variation. Nikolas saddled the donkey, which lived in a makeshift shelter next to the main house, along with a group of six goats and sheep which Aggeliki milked each morning, and left for the hills. The land he had inherited had never before been touched by human hands. He worked most of the day with some paid labourers clearing the land of the scrub wood and rocks, digging it up, tilling it, and planting it with olive trees. Aggeliki had filled a woven bag with bread, some olives, a chunk of graviera and a carafe of wine for Nikolas to curb his hunger, before he came back home at midday. It was usually too hot to work after that; the sun did not rest even in winter. The midday meal was a very silent affair, one that always heightened the void between the couple. They could not fill the space between them with their presence. They had little to say to each other; their world had become static. Without offspring, there was no one to work for but himself, and his wife, of course, who, at times, seemed to live in her own reticent world. Apart from his requests for better food and clean clothes to wear, he had very little to say to her. Yesterday, she had cooked youvarlakia in a tomato sauce, using the anidres tomatoes he had hung on the rafters of the house to dry for the winter, while the lemon tree was bulging from its own weight, laden with fruit. Hadn't she ever had youvarlakia? Didn't she know how to make an avgolemono sauce?

"What were you thinking, using the tomatoes I was saving for the winter? Where are we going to find them when we need them, woman!" He could hear the rumble in his own voice as he shouted at her. Usually the house was so quiet. He wasn't used to hearing himself speak like this. He left the house feeling more angry with himself than his wife.

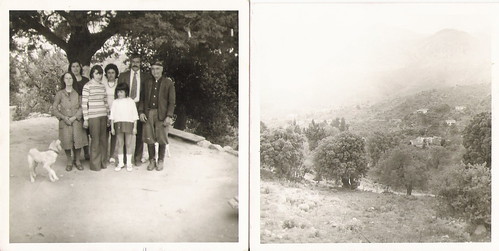

(Kambi village, 1974)

Things were not looking good in Smyrna: according to the front page, war was imminent. His mind immediately conjured up the image of his brother leaving the village to fight against the Bulgarians. What was it that his brother had said? "In Ameriki, people are prepared to fight for their freedom. How can I stand and watch when my country is in danger?" Did he understand what he was fighting for? Had he thought about whether the cause was worth fighting for? Did he know how close the war was to the end when he lay sick and dying? Nikolas did not share his brother's patriotism. He did not want to fight a war that he hadn't started. He did not wish to be one of the victims of war like his brother. Now seemed a good time to leave the village, maybe even the island, and why not the country if it got to that stage. The shame of childlessness could be avoided if he simply lived elsewhere, far away from anyone who knew him. Nikolas put it in his mind to seek a passage to Ameriki.

(The kind of Crete Nikolas and Aggeliki left when they decided to emigrate to Ameriki; these photos are more recent than the first set above. The photographs are works by George Meis, taken from a souvenir calendar of Crete)

(END OF PART ONE)

*** *** ***

Aggeliki may not have been too far wrong when she made youvarlakia with a tomato-based sauce. (In any case, her cooking improved once she went to Ameriki.) Youvarlakia is a meatball dish, in which the meatballs are made with rice, and cooked in an egg-and-lemon sauce, which turns them into a light main meal. My aunt in New Zealand used to make them, but not my mum; they simply didn't become a favorite in our house, along with, funnily enough, pastitsio, an all-time favorite Greek pasta dish.

The next time I had youvarlakia was in a hospital in Iraklio where my new-born son was under observation for an extremely rare blood disorder: at the age of two months, we discovered that he wasn't producing enough blood to supply his body with, which did thankfully clear up on its own when he was ten months old. He had six blood tranfusions in between this period. The hospital youvarlakia were cooked in the tradtional egg-and-lemon sauce, which my husband was never a great fan of. I enjoyed them, despite the hospital atmosphere.

My husband laughed them off : "They forgot the tomato," he said.

"But youvarlakia aren't cooked in tomato," I replied.

"Yes, they are," he said as we looked at each other wondering whether we were from different planets.

When life became a little more normal in our house after the hospital episodes, I cooked youvarlakia with the tomato sauce my husband liked, which, of course, was the way he had been brought up to eat them. I didn't really like them, but then I've never been a fan of tomato-based sauces. I'd rather eat garbanzo beans (chickpeas) than fasolada; I prefer a carbonara to a makaronada; give me a lettuce salad rather than the traditional Greek horiatiki. This is the reason why I prefer an avgolemono meat dish to my regular tomato-stew meat dishes, and believe me, youvarlakia in avgolemono are delicious. I have found one recipe (in Chrissa Paradissis' Greek Cookery, 1983 edition) that insists on using tomato AND egg-and-lemon sauce together to make youvarlakia, but mixing tomato and lemon is a rarity.

Aggeliki's cooking probably got better once she went to Ameriki, because life simply became less mundane and the tasks she performed in Crete on a daily basis probably became automated in Ameriki. Her kitchen would have been more well-fitted, her food did not have to be sourced straight from the fields, her house probably never resembled a mud-hut. And Nikolas was probably a happier man once he moved to Ameriki, because he would have found better working conditions and an appropriate salary. But the food they ate together wherever they set up home would still have been traditional Greek food, even if the ingredients weren't easily available.

(The video shows how Cretan families from Kambi were living in California in 1948; Crete at that time was extremely poor, while Greece was in the midst of a civil war. To the average Cretan, this picture would have seemed like a scene from paradise; poverty remains the main reason why, up to the late 1970s, Greek people emigrated to the New Worlds.)

Galatia in California makes her youvarlakia in the traditional Greek way. I got the recipe straight from her son Nick, who could well have been Nikolas' grandson. The recipe is exactly as he related it to me, with a couple of exceptions. I added a large onion (I am a great fan of all Allium species: onion, garlic, and leek), I used only two eggs, and I added olive oil to the pot after cooking the recipe according to Nick's instructions. The reason why is a simple Cretan one: we cannot do without our olive oil. It may add to the calories, but it will also add to the flavour; it also removes the eggy taste that my family isn't used to in their sauces. The original recipe before adding the olive oil - Galatia's youvarlakia are just so good with that extra dose of garlic - reminded me of the way my mother cooked Greek food in New Zealand. When you don't have access to cheap, high-quality olive oil (as we do in Crete), you go without. Tough luck.

Since we don't eat youvarlakia often, you may be wondering if my fussy eaters actually ate this. As it was the first time I made this meal, I decided to soften it a little with a side dish of fried potatoes. I called the youvarlakia by another familiar name for mince balls, biftekia, which use the same ingredients, except that the rice is replaced with breadcrumbs. Next time I serve it, it won't be with potatoes, but with extra sauce to mop up with bread. After that, I might even call them by their real name, youvarlakia, and turn the sauce into a soup like Peter's. Evelyn also added a few chunky vegetables to it and turned it into a hearty meal for a cold day.

I know that, like leek and potato potage, first introduced to me by Ioanna, youvarlakia are going to become a firm family favorite. When I served up the youvarlakia for lunch, I had left the pot on the table. My husband asked me to take it away because "I could eat right out of it and not stop till I get to the bottom of the pan."

For the meatballs, you need:

1 pound of ground beef (about 450-500 grams)

1/2 onion, grated

4 to 5 garlic cloves (minced or grated)

1/2 cup rice (we use "Barba Ben's" long-grain)

1 egg

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

salt & pepper to taste

a little olive oil

For the sauce, you need: some butter, 3 eggs and 1/2 cup lemon juice

Mix the meatballs ingredients together well, and then make into small balls (about the size of walnuts). The one thing I always keep in mind is to keep the meatballs themselves small, more of a walnut size than a golfball. It took me a while to remember that the rice will cook and puff up in size.

Melt the butter in a large pot and place the meatballs in a single layer on the bottom (if you've made more meatballs than can fit in your pot, you can stack up a second layer). Cover the meatballs with water, going about 1/2 inch above the top layer of meatballs. Bring to a boil and let them cook at a low boil/high simmer for 20 to 25 minutes (until the rice has cooked, but keeping careful not to let all the water evaporate - you need the cooking liquid for the avgolemono).

Mix the eggs with 1/2 cup lemon juice and beat until frothy. Slowly add in the liquid from the meatballs and continue beating. Pour the avgolemono mixture back on top of the meatballs. If the avgolemono is too runny, or if the meatballs have sat around for a while (which is fine, and I should add that the meatballs, even without the avgolemono, are delicious) you can heat the whole mixture back on the stovetop, either to thicken the avgolemono, or to bring it back to a warm temperature, or both.

This post is dedicated to all the Cretans from Kambi, my mother's village, living in Modesto and Manteca, California, where very many of them congregated. It doesn't matter where they were born, whether it was in Crete or America, or whether they continue to speak Greek or not; they are still Greek at heart, and they know it. Thanks are due to Galatia Aretakis and her son Nick, because without their participation in this post, I would never have made youvarlakia.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

The next time I had youvarlakia was in a hospital in Iraklio where my new-born son was under observation for an extremely rare blood disorder: at the age of two months, we discovered that he wasn't producing enough blood to supply his body with, which did thankfully clear up on its own when he was ten months old. He had six blood tranfusions in between this period. The hospital youvarlakia were cooked in the tradtional egg-and-lemon sauce, which my husband was never a great fan of. I enjoyed them, despite the hospital atmosphere.

My husband laughed them off : "They forgot the tomato," he said.

"But youvarlakia aren't cooked in tomato," I replied.

"Yes, they are," he said as we looked at each other wondering whether we were from different planets.

When life became a little more normal in our house after the hospital episodes, I cooked youvarlakia with the tomato sauce my husband liked, which, of course, was the way he had been brought up to eat them. I didn't really like them, but then I've never been a fan of tomato-based sauces. I'd rather eat garbanzo beans (chickpeas) than fasolada; I prefer a carbonara to a makaronada; give me a lettuce salad rather than the traditional Greek horiatiki. This is the reason why I prefer an avgolemono meat dish to my regular tomato-stew meat dishes, and believe me, youvarlakia in avgolemono are delicious. I have found one recipe (in Chrissa Paradissis' Greek Cookery, 1983 edition) that insists on using tomato AND egg-and-lemon sauce together to make youvarlakia, but mixing tomato and lemon is a rarity.

Aggeliki's cooking probably got better once she went to Ameriki, because life simply became less mundane and the tasks she performed in Crete on a daily basis probably became automated in Ameriki. Her kitchen would have been more well-fitted, her food did not have to be sourced straight from the fields, her house probably never resembled a mud-hut. And Nikolas was probably a happier man once he moved to Ameriki, because he would have found better working conditions and an appropriate salary. But the food they ate together wherever they set up home would still have been traditional Greek food, even if the ingredients weren't easily available.

(The video shows how Cretan families from Kambi were living in California in 1948; Crete at that time was extremely poor, while Greece was in the midst of a civil war. To the average Cretan, this picture would have seemed like a scene from paradise; poverty remains the main reason why, up to the late 1970s, Greek people emigrated to the New Worlds.)

Galatia in California makes her youvarlakia in the traditional Greek way. I got the recipe straight from her son Nick, who could well have been Nikolas' grandson. The recipe is exactly as he related it to me, with a couple of exceptions. I added a large onion (I am a great fan of all Allium species: onion, garlic, and leek), I used only two eggs, and I added olive oil to the pot after cooking the recipe according to Nick's instructions. The reason why is a simple Cretan one: we cannot do without our olive oil. It may add to the calories, but it will also add to the flavour; it also removes the eggy taste that my family isn't used to in their sauces. The original recipe before adding the olive oil - Galatia's youvarlakia are just so good with that extra dose of garlic - reminded me of the way my mother cooked Greek food in New Zealand. When you don't have access to cheap, high-quality olive oil (as we do in Crete), you go without. Tough luck.

Since we don't eat youvarlakia often, you may be wondering if my fussy eaters actually ate this. As it was the first time I made this meal, I decided to soften it a little with a side dish of fried potatoes. I called the youvarlakia by another familiar name for mince balls, biftekia, which use the same ingredients, except that the rice is replaced with breadcrumbs. Next time I serve it, it won't be with potatoes, but with extra sauce to mop up with bread. After that, I might even call them by their real name, youvarlakia, and turn the sauce into a soup like Peter's. Evelyn also added a few chunky vegetables to it and turned it into a hearty meal for a cold day.

I know that, like leek and potato potage, first introduced to me by Ioanna, youvarlakia are going to become a firm family favorite. When I served up the youvarlakia for lunch, I had left the pot on the table. My husband asked me to take it away because "I could eat right out of it and not stop till I get to the bottom of the pan."

For the meatballs, you need:

1 pound of ground beef (about 450-500 grams)

1/2 onion, grated

4 to 5 garlic cloves (minced or grated)

1/2 cup rice (we use "Barba Ben's" long-grain)

1 egg

2 tablespoons chopped parsley

salt & pepper to taste

a little olive oil

For the sauce, you need: some butter, 3 eggs and 1/2 cup lemon juice

Mix the meatballs ingredients together well, and then make into small balls (about the size of walnuts). The one thing I always keep in mind is to keep the meatballs themselves small, more of a walnut size than a golfball. It took me a while to remember that the rice will cook and puff up in size.

Melt the butter in a large pot and place the meatballs in a single layer on the bottom (if you've made more meatballs than can fit in your pot, you can stack up a second layer). Cover the meatballs with water, going about 1/2 inch above the top layer of meatballs. Bring to a boil and let them cook at a low boil/high simmer for 20 to 25 minutes (until the rice has cooked, but keeping careful not to let all the water evaporate - you need the cooking liquid for the avgolemono).

Mix the eggs with 1/2 cup lemon juice and beat until frothy. Slowly add in the liquid from the meatballs and continue beating. Pour the avgolemono mixture back on top of the meatballs. If the avgolemono is too runny, or if the meatballs have sat around for a while (which is fine, and I should add that the meatballs, even without the avgolemono, are delicious) you can heat the whole mixture back on the stovetop, either to thicken the avgolemono, or to bring it back to a warm temperature, or both.

This post is dedicated to all the Cretans from Kambi, my mother's village, living in Modesto and Manteca, California, where very many of them congregated. It doesn't matter where they were born, whether it was in Crete or America, or whether they continue to speak Greek or not; they are still Greek at heart, and they know it. Thanks are due to Galatia Aretakis and her son Nick, because without their participation in this post, I would never have made youvarlakia.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

I was wondering where that story was going...To me, giouvarlakia are the ultimate comfort food...the best. Like your husband, I could easily consume a pot in one sitting! Personally, I've never seen or tasted a tomato version...and another thing, Cretans aren't the only ones who add oil to the pot. The Spartans do it too!

ReplyDeleteMy mother used to make them so often I got sick of them. I still don't like them. Strangely enough I like courgettes avgolemono, which is basically the same recipe plus the courgettes! Anyway, my mom used to add a tiny bit of tomato pelte to turn the sauce pink! I loved the story. All this emigration was very painful for Greece.

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing these stories with us. These are the authentic recipes I love to recreate. I found a web site where they make Greek dishes as the ancients did with ground sesame seeds in the dough , poppy seeds in the multi nut filling. I want to try that one of these days as well:D

ReplyDeleteThese sound a lot like what my Yiayia made, she called them Dolomathes without the grape leaves. I think she used to make these when she didn't have time to wrap! Her Dolomathes were always made avgokomeno. She made at least a hundred at a time, because three families would stop by on our way home from school and pick-up a pot full for dinner. It wasn't until I was much older that I had what I call the deli-style of Dolomathes, sold today.

ReplyDeleteMy mom makes Lamb with Celery, avgokomeno. There are tomatoes in that prior to the sauce being added. When foodjunkie mentioned the pink sauce I got a flashback to the one thing my mom made with a pink sauce! Odd looking for sure, but tasted pretty good.

What a grear, great post Maria. Congratulations!

ReplyDeletea fascinating story. :O and such beautiful images to go with it.

ReplyDeleteI love Yiouverlakia and I feel like a kid each time I eat a big bowl of it..glad you added it to your recipe listing (thank you for the link).

ReplyDeleteLetters from readers like this one are so wonderful, fuel for future blog posts and an inspiration.

Oh Maria, how wonderful that you received such a lovely letter from one of your readers!

ReplyDeleteI enjoyed the bitter sweet story of Nikolas and Aggeliki. Even more, I enjoyed reading about this lovely meatball dish. Your meatball recipe is one that I've enjoyed, but I've never had that sauce. You know, of course, that I want to try it now! I smiled at your addition of Olive oil! We Italians love that lovely oil, too! Love that close up shot.

And, your children are ADORABLE! Look at your daughter's lovely eyes! And your son looks so handsome! How scary that must have been when was hospitalized when he was a baby. I'm so glad that that is behind all of you.

GREAT post!

Nice story.

ReplyDeleteAs it happens my wife (who is not Greek) made this for us this weekend!

It is a great dish, very filling, and fairly inexpensive to make too. I'm surprised you have not posted it before.

I enjoyed reading through some of your blog posts and learning so much history and look forward to future posts.

ReplyDeleteRegarding your comment about the foodie book club, we are somewhat relying on Johanna of Food Junkie to let us know which books are readily available in Europe for our book picks (we canceled our initial selection by Karen Allison "How I Gave My My Heart to the Restaurant Business" when she found it was too scarce and swapped in "La Cucina").

The reading lists mentioned in our Cook the Books book club are just meant to offer people ideas for picking the next reading selection, so I would love to hear your input. By no means did we want to have people purchase all of them.

We're planning to have more lead time for our readers to purchase or borrow the upcoming Cook the Books selections, maybe three picks ahead of time, so look for that.

In the meantime, I would be happy to send you my copy of "La Cucina" if you are having trouble getting one in Crete. Just leave me a comment at the Crispy Cook.

Indeed, Maria, the history of Greek emigration is dotted with tragedies, sacrifices, exploitation and the drama of thousands of men, women, children, forced to eradicate from their own country in order to find better opportunities abroad.

ReplyDeleteThe version of youvarlakia in tomato sauce is characteristic of southern Greece. Both versions are mentioned in the cookbooks from late 19th- early 20th century. The combination of tomato sauce with eggs and lemon is familiar to Western Greece.

As am American, married to a Greek from Greece, for 37 years, I find your site, and your recipes really fun.

ReplyDeleteI have been to Crete once. My husband was stationed there in the Coast Guard in 1969 (?)

I made gouvoulrakia for my family often. It was a winter standby for us. I think it is 2 out for 3 kids favorites!! They used to ask for it on their birthday!!

My husband is from Ios, which is on the way to Crete!!

Ha! That's my mom,susan, who posted about 2 out of 3 of us loving this! I am one of the two. this is my all time favorite food, i will have to try this recipe.

ReplyDeleteThanks!

christina

Well I'm a vegetarian so won't be trying it, but I still relished the pictures and your writing :)

ReplyDeletemy mom made almost the exact receipe and she made it at times with tomato and other times with avgolemono. she was from smryna and a great cook! we just lost her.

ReplyDeleteit's a great meal, and it'll be a great way to remember your mum when you make it

ReplyDelete