I recall a

moment when my way of thinking, being influenced by the people who

raised me, in combination with my lack of contact with the mainstream

community (due, I suppose, to my parents' avoiding it wherever possible), except as a school pupil/university student/shop assistant, made me get a low mark in a school assignment. I remember this incident with as much clarity as is

possible given that it took place over 30 years ago, in my first year of

being in a 'clever girls' class group at an academically-inclined

mainstream Kiwi high school in the early 1980s, where the subject called simply 'English' was compulsory for all

high school students. Generally speaking, I never did do very well in English throughout the three years that I had to take it at high school; my mother thought this to be an indication of my lack of essay writing skills (and I believed her).

In English, we studied a bit of grammar, some essay

writing, and quite a bit of English literature chosen among well known

British and American authors and titles (eg Shakespeare, To Kill a Mockingbird), as well as the young

but growing list of New Zealand works of literature. We read Katherine Mansfield's short stories of life in early New Zealand, some of whose works were set in Wellington near my school area (she was a WGC Old Girl). They show her highly developed people-observation skills depicting the relationships of a fledgling British colony which was establishing some kind of identity modelled on another country. The Doll's House is a good example of this. :

The God Boy by Ian Cross served to remind us that we are not to blame for who raised us. The story (published in 1957) was a rather sad one of a troubled youngster, but it had its funny moments too. Jimmy Sullivan went to a Catholic school, and one day when he didn't feel like participating class activities, he told a nun that he wasn't able to go swimming (I think - I cannot find an online copy of the book to verify this) because he had his period, something he had heard from his sister.

My first introduction to Maori stories was through Pounamu, Pounamu by Witi Ihimaera, whose works revolved around rural life in Maori families; as a child with an immigrant background, I could relate to these stories very well; Maori and Greeks were minority groups living among an Anglo-Saxon majority. Ihimaera wrote as a reaction against the belief that there were no Maori writers in New Zealand at the time, writing the stories he himself wanted to read, which were missing from the available literature. (Andrea Levy does the same thing - she is another of my favorite writers.) Pounamu, Pounamu is still described as something every Kiwi should read, even 40 years on. The stories naturally contain many references to racial prejudice, written from both the Maori and the pakeha point of view:

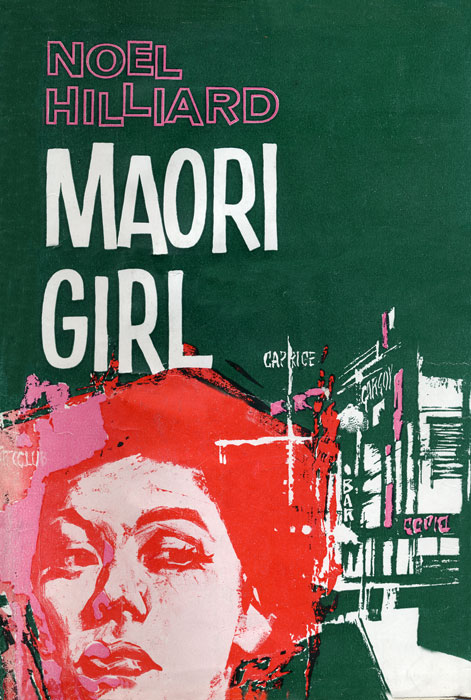

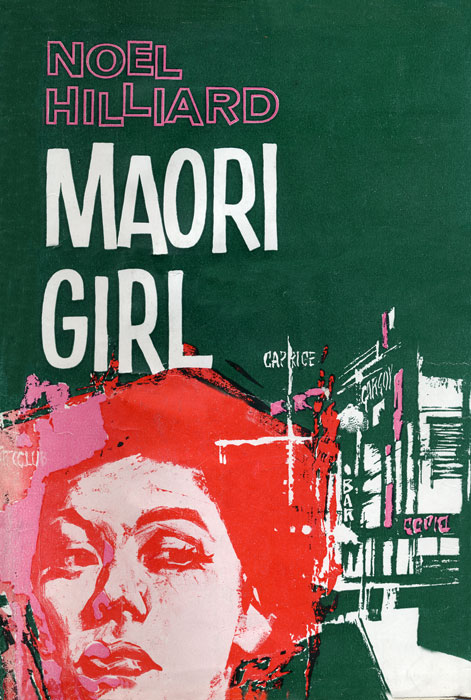

Maori Girl

by Noel Hilliard.is not a savoury novel. It shows us what happens when someone falls out of favour with their rural family, drifts into the city without any guidance and ends up in a state of moral and financial difficulty. In other words, it tells us a familiar story which arouses the mixed feelings of shame, guilt and compassion. Such stories rarely have a happy ending and they are dictated with a "preconceived conclusion" which ends up in predictable tragedy. The story is meant to highlight racial prejudice and social disintegration, but as it also depicts alcohol abuse and promiscuity, it serves as an illustration of corrupted morality.

Netta, a Maori girl, leaves her provincial home after quarrelling with her father who was against her doing pakeha things (she was seen with white men). She goes to Wellington, where she finds work as a cleaner in a boarding house. The company she keeps here led her to meeting the low-life pakeha Eric who moves in with her. After a bad relationship which also caused her to lose her job and home, she eventually meets pakeha Arthur after a casual night out. Arthur falls in love with Netta. Netta realises she's pregnant and Arthur makes arrangements for the baby's arrival. But he then realises that Netta was pregnant before he met her, and he breaks up with her, although he feels shame and guilt for what he does:

Netta, a Maori girl, leaves her provincial home after quarrelling with her father who was against her doing pakeha things (she was seen with white men). She goes to Wellington, where she finds work as a cleaner in a boarding house. The company she keeps here led her to meeting the low-life pakeha Eric who moves in with her. After a bad relationship which also caused her to lose her job and home, she eventually meets pakeha Arthur after a casual night out. Arthur falls in love with Netta. Netta realises she's pregnant and Arthur makes arrangements for the baby's arrival. But he then realises that Netta was pregnant before he met her, and he breaks up with her, although he feels shame and guilt for what he does:

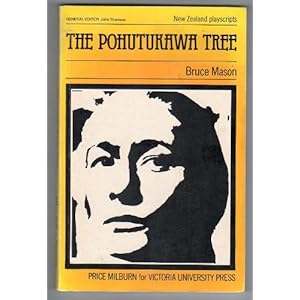

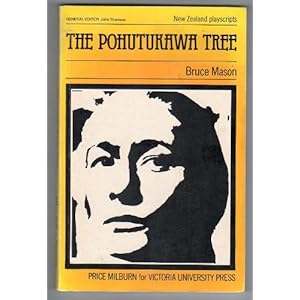

We also studied Bruce Mason's play The Pohutukawa Tree, published at about the same time as Maori Girl (1960), which also dealt with a Maori girl's pregnancy to a pakeha. In this case, Roy didn't want to marry Queenie, because she was Maori. Even though he liked her, he perceived that the differences between their cultures were too great. Queenie's mother dies from the grief she felt of the decline in Maori values of her children (her son had smashed up a church in a fit of rage).

We also studied Bruce Mason's play The Pohutukawa Tree, published at about the same time as Maori Girl (1960), which also dealt with a Maori girl's pregnancy to a pakeha. In this case, Roy didn't want to marry Queenie, because she was Maori. Even though he liked her, he perceived that the differences between their cultures were too great. Queenie's mother dies from the grief she felt of the decline in Maori values of her children (her son had smashed up a church in a fit of rage).

We read parts of Maori Girl and The Pohutukawa Tree in class and for homework, and the teacher also gave us an assignment to complete on them. Although I can't remember the exact wording of the questions, one was something to the likes of:

The assumption of right/wrong answers in a society that was made up of various cultures was not really a good one on the part of the teacher. The view of morality was from the side of the pakeha, but it was also the pakeha that created the situation that corrupted Netta and Queenie. My own Greekness in this case could be said to have been viewed indirectly by the teacher as simply a part of my adjustment process in multi-cultural New Zealand. In other words, it would only be a matter of time that I would start to see things in the more 'correct' manner.

But even though political correctness has come a long way in the western world, the way the world is now shaping itself shows that we still have a long way to go yet. Some ideas will never quite be politically correct because they are too enshrined in a non-liberal framework which work differently for different cultures. When we can't agree on how an issue must be handled, we have to agree that we are indeed different, and not the same at all.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

Iconic New Zealand literature

NZ-born Mansfield was educated in England, and eventually left NZ, preferring Europe where she eventually died after a rather eccentric and very troubled life.... the school the Burnell children went to was not at all the kind of place their parents would have chosen if there had been any choice. But there was none. It was the only school for miles. And the consequence was all the children in the neighborhood, the judge's little girls, the doctor's daughters, the store-keeper's children, the milkman's, were forced to mix together... But the line had to be drawn somewhere. It was drawn at the Kelveys. Many of the children, including the Burnells, were not allowed even to speak to them. They walked past the Kelveys with their heads in the air, and as they set the fashion in all matters of behaviour, the Kelveys were shunned by everybody. Even the teacher had a special voice for them, and a special smile for the other children when Lil Kelvey came up to her desk with a bunch of dreadfully common-looking flowers. They were the daughters of a spry, hardworking little washerwoman, who went about from house to house by the day. This was awful enough. But where was Mr. Kelvey? Nobody knew for certain. But everybody said he was in prison. So they were the daughters of a washerwoman and a gaolbird. Very nice company for other people's children!

The God Boy by Ian Cross served to remind us that we are not to blame for who raised us. The story (published in 1957) was a rather sad one of a troubled youngster, but it had its funny moments too. Jimmy Sullivan went to a Catholic school, and one day when he didn't feel like participating class activities, he told a nun that he wasn't able to go swimming (I think - I cannot find an online copy of the book to verify this) because he had his period, something he had heard from his sister.

My first introduction to Maori stories was through Pounamu, Pounamu by Witi Ihimaera, whose works revolved around rural life in Maori families; as a child with an immigrant background, I could relate to these stories very well; Maori and Greeks were minority groups living among an Anglo-Saxon majority. Ihimaera wrote as a reaction against the belief that there were no Maori writers in New Zealand at the time, writing the stories he himself wanted to read, which were missing from the available literature. (Andrea Levy does the same thing - she is another of my favorite writers.) Pounamu, Pounamu is still described as something every Kiwi should read, even 40 years on. The stories naturally contain many references to racial prejudice, written from both the Maori and the pakeha point of view:

Could the children have done it though? Could they have gone into the henhouse? No.... But you couldn't blame Jack for thinking that tehy had, could you? No, you couldn't .... Stil, he shouldn't have hit Henare. That was unforgiveable. What a mess, what an awful mess. Every conflict with the Heremaias has been a mess. Of suspicion, of doubt, of accusations proven or unproven. If only the Heremaias weren't so large, so obvious. They stick out like a sore thumb in the neighbourhood. they have not yet learnt the art of living with European people who may not understand their ways nor like them. They are essentially good people, but oh so tactless and troublesome at time... Is it any wonder that when some accident happens in the street the Heremaia children are blamed? They bring it upon themselves, really they do!

Netta, a Maori girl, leaves her provincial home after quarrelling with her father who was against her doing pakeha things (she was seen with white men). She goes to Wellington, where she finds work as a cleaner in a boarding house. The company she keeps here led her to meeting the low-life pakeha Eric who moves in with her. After a bad relationship which also caused her to lose her job and home, she eventually meets pakeha Arthur after a casual night out. Arthur falls in love with Netta. Netta realises she's pregnant and Arthur makes arrangements for the baby's arrival. But he then realises that Netta was pregnant before he met her, and he breaks up with her, although he feels shame and guilt for what he does:

Netta, a Maori girl, leaves her provincial home after quarrelling with her father who was against her doing pakeha things (she was seen with white men). She goes to Wellington, where she finds work as a cleaner in a boarding house. The company she keeps here led her to meeting the low-life pakeha Eric who moves in with her. After a bad relationship which also caused her to lose her job and home, she eventually meets pakeha Arthur after a casual night out. Arthur falls in love with Netta. Netta realises she's pregnant and Arthur makes arrangements for the baby's arrival. But he then realises that Netta was pregnant before he met her, and he breaks up with her, although he feels shame and guilt for what he does: ... the point of Arthur's guilt and dissatisfaction is to pass on to the pakeha reader the guilt and dissatisfaction he should feel at what his society has done to Netta..., and any one of dozens of other Maori girls.

We also studied Bruce Mason's play The Pohutukawa Tree, published at about the same time as Maori Girl (1960), which also dealt with a Maori girl's pregnancy to a pakeha. In this case, Roy didn't want to marry Queenie, because she was Maori. Even though he liked her, he perceived that the differences between their cultures were too great. Queenie's mother dies from the grief she felt of the decline in Maori values of her children (her son had smashed up a church in a fit of rage).

We also studied Bruce Mason's play The Pohutukawa Tree, published at about the same time as Maori Girl (1960), which also dealt with a Maori girl's pregnancy to a pakeha. In this case, Roy didn't want to marry Queenie, because she was Maori. Even though he liked her, he perceived that the differences between their cultures were too great. Queenie's mother dies from the grief she felt of the decline in Maori values of her children (her son had smashed up a church in a fit of rage). We read parts of Maori Girl and The Pohutukawa Tree in class and for homework, and the teacher also gave us an assignment to complete on them. Although I can't remember the exact wording of the questions, one was something to the likes of:

How do you feel about Arthur's/Roy's behaviour at the end of his relationship with Netta/Queenie? Was he justified in breaking up with Netta/Queenie?If you're a Greek girl and you've been raised by Greek parents in a non-Greek environment, you'll know that both Arthur's and Roy's behaviour was hardly surprising and that they would both dump their girlfriends (because they weren't very stable characters. Your mother would have warned you about them too. You'd feel sorry for Netta/Queenie, but you would also know that the pressure she would be facing in this situation would not allow for greater leniency to be shown towards her. Netta and Queenie had in a way made the bed they were lying on (at the age of 15, you'd be influenced by your mother on this one). Arthur and Roy left a relationship as freely as they had entered it, so they could never have been that reliable in a relationship which carried responsibility. ("Good Greek boys don't just turn up out of nowhere", I can imagine my mother saying.) Arthur also felt lied to, while Roy had to face the pressures of his own family's beliefs. Maybe it's ultimately the way Netta's parents would have felt too had they known about their daughter's pregnancy; Queenie's mother in fact did want her daughter to have a wedding (but not a white one, with the knowledge that she was already pregnant):

"It is in fact the commonest failing in the attitude of people who claim to be sympathetic to Maoris that they will not appreciate that there are differences in the traditions, the outlook and the aspirations of Maoris, and further, that many of these differences are an advantage in that they enable Maoris to cope with the changes that social, economic and policy pressures are forcing on them. Many socialists, like many other pakehas, assume that such differences are inferiorities; and one is likely to be called a racialist if one insists on them."The above quote comes from a review of Maori Girl, written a year after the book appeared (1960). It helps that I read this now as I try to justify my own opinions back then. We mainly remember the surface details of such sad stories:

... it is the subsequent and much simpler sequence of events that most pakeha readers will remember: and socialists should be careful not to fall for the temptation to take this as simply an indictment of landladies and restaurateurs who either discriminate against Maori girls or exploit them: the contemplation of such practices, because one condemns them, can give one a very smug conscience. For this section of the book is an accusation against pakeha society itself, the assumptions of which are shared by a great number of those who condemn racial discrimination.I didn't have this review on hand to show my English teacher, and it is indeed interesting to see the book being discussed in this way as early as 1961, when political correctness was not even a concept then. I completed the assignment, writing as honestly as I thought I should, from my own experiences, without asking my parents (who would have been astounded to think that this kind of reading material was being used with 15-year-olds) or getting any other help. But in my liberal-minded mainstream (and at the time predominantly pakeha) New Zealand high school, socialist ideals, liberal thinking and compassionate protestantism were being drummed into our minds, and my kind of answer just happened to be 'wrong'. I recall the teacher's remarks: something about taking Netta's predicament into more consideration and the fact that Arthur was actually in love with her, so he could have been a father to her baby, even if it wasn't his. Roy too was in love with Queenie, and the racial issue should not have been considered before others.

The assumption of right/wrong answers in a society that was made up of various cultures was not really a good one on the part of the teacher. The view of morality was from the side of the pakeha, but it was also the pakeha that created the situation that corrupted Netta and Queenie. My own Greekness in this case could be said to have been viewed indirectly by the teacher as simply a part of my adjustment process in multi-cultural New Zealand. In other words, it would only be a matter of time that I would start to see things in the more 'correct' manner.

But even though political correctness has come a long way in the western world, the way the world is now shaping itself shows that we still have a long way to go yet. Some ideas will never quite be politically correct because they are too enshrined in a non-liberal framework which work differently for different cultures. When we can't agree on how an issue must be handled, we have to agree that we are indeed different, and not the same at all.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

I remember reading "The Dollhouse" in 10th grade English class...all I remember is something about cold mutton sandwiches.

ReplyDelete