I suppose I could do a million things on New Year's Eve, like book a table at a restaurant (too expensive), go to a party (I haven't been invited), stage a party (everyone's going to other parties), or go to the town centre (and stand in the cold and rainy weather outside the Agora till the New Year rings in), but I prefer to spend it at my comfortable warm home, in my peace and quiet, being silly with my family. It's what comes from having a small family with few relatives at the same stage in life as we are in. Nearly all our friends keep things in the family, as do most people living in Crete, once they settle down with families of their own.

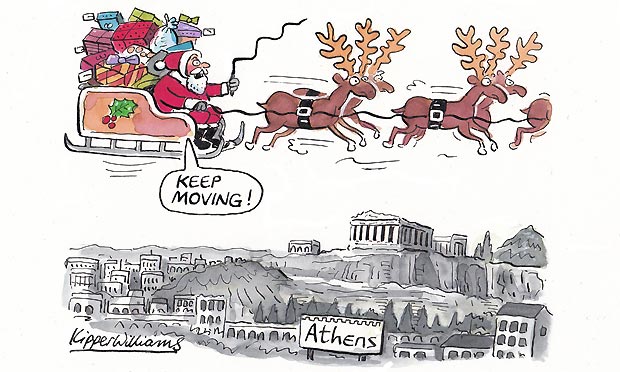

Card-playing is common on this night as a Greek New Year's Eve tradition, as we wait for St Basil to come tomorrow, some time after we go to sleep, hopefully carrying some presents. I've got a lunch party planned at my place tomorrow, so I will find myself pre-occupied preparing food until then. And when the New Year comes, I'll probably find myself looking at the fireworks from the panoramic view my balcony affords me, as my husband shoots blanks in the air.

Here are a few jokes to add a bit of silliness to your evening wherever you are - they all come from the old-fashioned (but much-loved by the Greek diaspora) iconic Greek page-a-day calendar, which is found at all stationery-cum-bookshop stores all over Greece. You won't find it at the 'purely-for-book-lovers' bookshops in Athens, though; it's one of those things that separates the urbanite from the rural at heart, The page-a-day calendar was a recipe-based one, which included some food jokes.

Enjoy... and Happy New Year.

Strawberries

Someone is passing outside Dimitraki's house, holding a large sack on his shoulder.

“What are you carrying there?” asked Dimitraki.

“Manure, to put on my strawberries,” the passerby tells him.

“Hmm,” says Dimitraki, “I put sugar on my mine!”

Chemistry

“Dimitraki,” the chemistry teacher says, “Tell us what sulphuric acid is.”

“Er, yes,” mumbled Dimitraki, “it’s… it’s… it’s on the tip of my tongue—“

“Spit it out quickly, boy! It’s poisonous!”

“No,” says Dimitraki, “I don’t need to, because my mum is a really good cook!”

Greengrocer

Dimitraki isn’t very good with sums, so his mum tries to help him.

“Let’s say that you are a greengrocer and I am your customer. I buy 1kg potatoes that cost 100 drachmas a kilo, and 1kg tomatoes that cost 200 drachmas a kilo. How much money must I give you?”

“It doesn’t matter,” Dimitraki answered. “You can pay me tomorrow.”

Milk

Dimitraki’s teacher asks him:

“Why is your essay on the topic of ‘milk’ so short? Did you run out of things to write about?”

“No,” Dimitraki answers, “but I wanted to write about the condensed version.”

Hungry

Dimitraki was going for a walk with his dad. Before they set off, his dad told him to shine his shoes.

“They’ll just get dirty again, dad,” Dimitraki said.

After they came back home from the walk, Dimitraki told his dad that he was hungry.

“Well, Dimitraki, there’s no need to eat now, since you’re just going to get hungry again later!”

Fisherman

Dimitraki’s mother is giving her son some advice. “Dimitraki, to succeed in life, you must have patience, like that fisherman there, for example, who is sitting so patiently, and fishing for hours, to make his daily bread.” “Really mummy,” Dimitraki was amazed. “Since when did the sea start producing bread?”

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

Card-playing is common on this night as a Greek New Year's Eve tradition, as we wait for St Basil to come tomorrow, some time after we go to sleep, hopefully carrying some presents. I've got a lunch party planned at my place tomorrow, so I will find myself pre-occupied preparing food until then. And when the New Year comes, I'll probably find myself looking at the fireworks from the panoramic view my balcony affords me, as my husband shoots blanks in the air.

Here are a few jokes to add a bit of silliness to your evening wherever you are - they all come from the old-fashioned (but much-loved by the Greek diaspora) iconic Greek page-a-day calendar, which is found at all stationery-cum-bookshop stores all over Greece. You won't find it at the 'purely-for-book-lovers' bookshops in Athens, though; it's one of those things that separates the urbanite from the rural at heart, The page-a-day calendar was a recipe-based one, which included some food jokes.

Enjoy... and Happy New Year.

Strawberries

Someone is passing outside Dimitraki's house, holding a large sack on his shoulder.

“What are you carrying there?” asked Dimitraki.

“Manure, to put on my strawberries,” the passerby tells him.

“Hmm,” says Dimitraki, “I put sugar on my mine!”

Chemistry

“Dimitraki,” the chemistry teacher says, “Tell us what sulphuric acid is.”

“Er, yes,” mumbled Dimitraki, “it’s… it’s… it’s on the tip of my tongue—“

“Spit it out quickly, boy! It’s poisonous!”

Coca-cola

Dimitraki’s dad sent him to the mini-market to buy some coca-cola. Dimitrakis entered the butcher’s by mistake. Not having realize where he was, he asked the butcher for some coca-cola. The butcher tells him that he doesn’t have anym and Dimitraki leaves. He goes home and tells his dad that the shop doesn’t have any coca-cola. His dad tells him to go again, so Dimitraki goes to the same shop and again asks for coca-cola. The butcher was angry and told him not to ask him the same question again, otherwise he’ll hang Dimitraki upside down. Dimitraki sees a sheep hanging upside down; on hearing that he will be hung upside down, he asks it: “Did you ask for coca-cola, too?”

Mother

“Dimitraki, do you say your prayers before you sit down for a meal?”“No,” says Dimitraki, “I don’t need to, because my mum is a really good cook!”

Greengrocer

Dimitraki isn’t very good with sums, so his mum tries to help him.

“Let’s say that you are a greengrocer and I am your customer. I buy 1kg potatoes that cost 100 drachmas a kilo, and 1kg tomatoes that cost 200 drachmas a kilo. How much money must I give you?”

“It doesn’t matter,” Dimitraki answered. “You can pay me tomorrow.”

Milk

Dimitraki’s teacher asks him:

“Why is your essay on the topic of ‘milk’ so short? Did you run out of things to write about?”

“No,” Dimitraki answers, “but I wanted to write about the condensed version.”

Hungry

Dimitraki was going for a walk with his dad. Before they set off, his dad told him to shine his shoes.

“They’ll just get dirty again, dad,” Dimitraki said.

After they came back home from the walk, Dimitraki told his dad that he was hungry.

“Well, Dimitraki, there’s no need to eat now, since you’re just going to get hungry again later!”

Fisherman

Dimitraki’s mother is giving her son some advice. “Dimitraki, to succeed in life, you must have patience, like that fisherman there, for example, who is sitting so patiently, and fishing for hours, to make his daily bread.” “Really mummy,” Dimitraki was amazed. “Since when did the sea start producing bread?”

Καλή Χρονιά!

Happy New Year!.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

.jpg)