(This story was read to an audience consisting of Stacy Dunn's family, at Thanksgiving, 2011; Stacy told me that her family all gathered

around the computer and read through all my correspondence with her, together with this story, and there wasn't a dry eye in the house!)

"You use a thick rolling pin to roll out your filo pastry?" My friend sounded surprised. I explained to her that I had gotten used to using this kind of rolling pin and found it trying on my palms to use a thin one.

"That's because you're not using it properly," Hrisida scolded me. "I use a thick rolling pin for the pizza pastry where I only stretch the dough. But for making a pita, you do need the thin one. You're supposed to roll the fyllo and press lightly from the centre outwardly to the ends. It's actually less physical effort than stretching constantly but you need the right tool and a bigger surface area to work. By stretching you can only reach a certain thickness. Even you know that, don't you?" Her voice then softened. "My grandma's rolling pin is very thin and very long. But you can't get one like this now. These days they're much shorter, because we make smaller pies.Our sini are smaller than what my grandmother had." The σινί (sini) is a large baking tray 60cm in diameter with low sides. "We do have a couple that she used to own lying in the storage space in our village home. But people still use them even now - you can see them in bougatsa shops."

"Is your grandmother still alive?" I asked her.

"No, no," she said, shaking her head. "She died a very long time ago." Even though she was smiling, Hrisida's face took on a dull tone, as if it had lost its colour. "My mother's mother was from Eastern Thrace. That's part of Turkey now. She made a lot of pitas. I was a bad eater as a child but I loved her pitas. They were chunky and very filling." He face suddenly lit up. "She also used to make a sweet pitta where she just rolled out the fyllo and then placed it in a circle in the baking tray. My grandma used to call it saragli but it had no filling or topping. All I remember was filo pastry sweetened with syrup. She baked it, maybe with butter and then just added syrup to it. It sounds so simple but for us children it was heaven. And it's strange, but I've never tasted it since then. Not from my mum, nor from my aunties who were very close to my grandma.

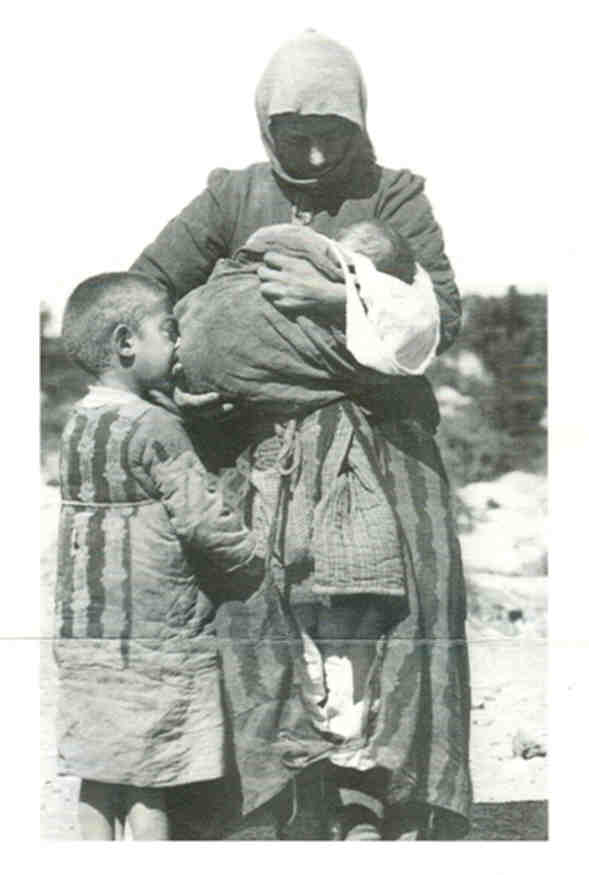

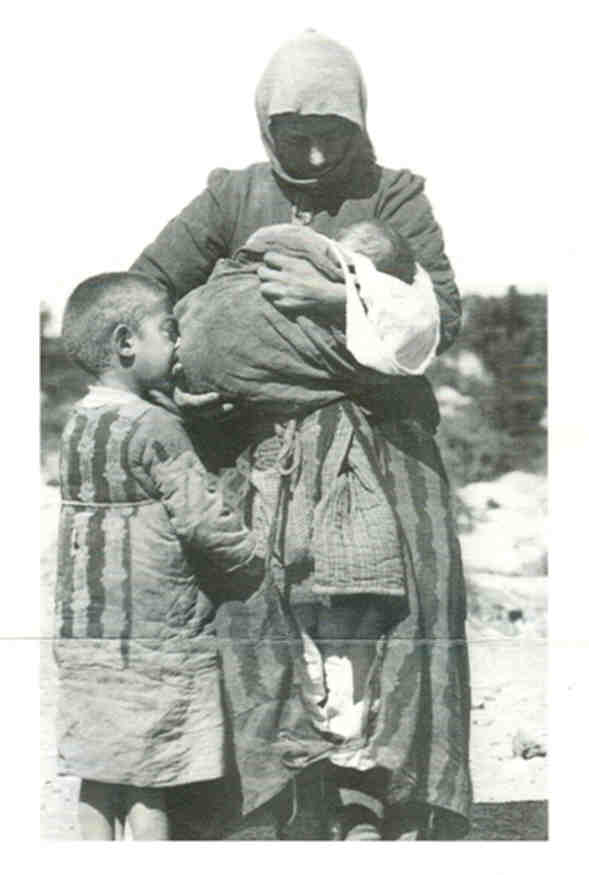

As Hrisida told me about her grandmother's story, I was conjuring up the images she was describing: an old woman, dressed in black, with a never-fading smile on her face, her back bent over, her pace quick but short. She would shuffle around her kitchen, preparing food for everyone, and never complain. If anyone told her to take it easy, she'd tell them she wasn't tired. I wondered what her life was like in Eastern Thrace before she came to Greece.

Hrisida's grandmother reminded me of Stacy Costas Dunn, a third generation Greek in the US who had recently contacted me about trying to track down her dead grandparents' hometown so that she could trace her roots and hopefully bring her American-born mother back to them on a holiday. Stacy had given me the names of the villages that were listed on the documents her grandfather was given when they arrived in Ellis Island: 'Kastaboli' (now Ormanli, meaning 'forest' in Turkish), 'Myriofytou' (now Murefte), 'Ghanochora' (now Gazikoy, possible also Hoskoy) - these were the birthplaces or last known homelands of Stacy's grandfather's family. Stacy remembers her family talking about Thrace (Θράκη). That's all she knew about her grandfather's homeland.

Since Stacy couldn't read Greek herself, I looked up the village names she had given me: Kaστάμπολη, Μυριοφύτου, Γανόχωρα to see what information I could find. There were half a dozen references to them, all of which directed me to the formerly Greek Eastern Thrace region, the little bit of land that is the only part of Turkey which is considered to be part of the European continent - hence where East meets West; only Western Thrace is now part of Greece. The change in land ownership led me to think that perhaps Stacy's family were refugees - did they by any chance leave Greece in or after 1922, when the Greek-Turkish population exchange took place? No, she informed me, her grandparents had migrated in 1912; her grandparents therefore could not have been involved in the population exchange. In that case, what caused them to leave Eastern Thrace?

Since Stacy couldn't read Greek herself, I looked up the village names she had given me: Kaστάμπολη, Μυριοφύτου, Γανόχωρα to see what information I could find. There were half a dozen references to them, all of which directed me to the formerly Greek Eastern Thrace region, the little bit of land that is the only part of Turkey which is considered to be part of the European continent - hence where East meets West; only Western Thrace is now part of Greece. The change in land ownership led me to think that perhaps Stacy's family were refugees - did they by any chance leave Greece in or after 1922, when the Greek-Turkish population exchange took place? No, she informed me, her grandparents had migrated in 1912; her grandparents therefore could not have been involved in the population exchange. In that case, what caused them to leave Eastern Thrace?

When Stacy's grandparents came to the US, as immigrants passing through Ellis Island, they would have suffered the stigma of the foreign-sounding name. Names were also often misspelled at the customs offices, as officials were left in the helpless position of transcribing what they think they heard from the newly-arrived non-English-speaking immigrant's mouth, often writing them incorrectly in official documents, which would have remained unchanged (ie uncorrected). Stacy had two possible names for her grandfather: 'Elias Sevricos' and 'Lee Costas', which, to the uninitiated would look wildly different from one another. Her grandfather was probably baptised 'Elias', which was probably changed to 'Lee' in America, while his surname 'Sevricos' was simply dropped - not only did it sound foreign, but it was also difficult to pronounce (again, to the uninitiated). Instead, he used his middle name, which, according to Greek tradition, is always your father's name: according to his US naturalization papers, his parents were Constantinos Sevricoz and Zafireia ('Sapphire', noted as 'Zafery' on the documents) Paraskeva (written as 'Paroskua'; in Modern Greek, 'eu' is pronounced as 'ev' or 'ef' depending on context, and the 'e' was probably seen as superfluous by the customs official).

When Stacy's grandparents came to the US, as immigrants passing through Ellis Island, they would have suffered the stigma of the foreign-sounding name. Names were also often misspelled at the customs offices, as officials were left in the helpless position of transcribing what they think they heard from the newly-arrived non-English-speaking immigrant's mouth, often writing them incorrectly in official documents, which would have remained unchanged (ie uncorrected). Stacy had two possible names for her grandfather: 'Elias Sevricos' and 'Lee Costas', which, to the uninitiated would look wildly different from one another. Her grandfather was probably baptised 'Elias', which was probably changed to 'Lee' in America, while his surname 'Sevricos' was simply dropped - not only did it sound foreign, but it was also difficult to pronounce (again, to the uninitiated). Instead, he used his middle name, which, according to Greek tradition, is always your father's name: according to his US naturalization papers, his parents were Constantinos Sevricoz and Zafireia ('Sapphire', noted as 'Zafery' on the documents) Paraskeva (written as 'Paroskua'; in Modern Greek, 'eu' is pronounced as 'ev' or 'ef' depending on context, and the 'e' was probably seen as superfluous by the customs official).

I recounted Stacy's plight to Hrisida. She agreed that the family's names had undergone an Americanised transformation, which was hindering Stacy from finding her roots. 'Zafiris' is a common Thracian name for men ('Zafireia' is the female variant of the same name). 'Myriofyto' is a village in the region of Kilkis in modern-day Greece, where many former Eastern Thracians settled after leaving their homelands. Interestingly, when we looked up the name 'Sivrikos' in the phone book, nothing came up, unlike for 'Paraskevas' which is relatively more common. If Paraskevas could be associated with the villages names of Kastaboli/Myriofytou, some connection pointing Stacy in the right direction could be made. Hrisida suggested some organisations in Northern Greece which look after the interests of people with roots in Eastern Thrace, like the Thrakiki Estia of Serres. Since we live in a more transparent and connected world, people can now also find the former Greek villages in Eastern Thrace and compare them with the Turkish villages in Google Earth.

The other issue of the personal names also had to be addressed. A web search of 'Sivrikoz' (that sounds like 'Sevricos') returns a

lot of hits where 'Sivrikoz' is used as a Turkish surname. But Stacy's grandparents' given names were clearly all Christian and Greek. How could that be possible? Could a Greek have taken on a Turkish surname in those troubled times and

places? Most likely, in the same way that people westernise their names to make them more 'likeable' to the general society. The

Sivrikoz name returned only two hits in the Greek telephone directory - but not as 'Sivrikos', only as 'Sivrikozis', a Greekifed form of 'Sivrikoz' by adding the very common ending '-is'. Again,

someone who came to Greece in 1918-1922 with the name 'Sivrikoz' would probably want to sound more Greek than Turkish. Greeks in Turkey at the time may have been coerced into changing their language and surnames but

they were allowed to keep their faith, hence the Christian names, in a similar way to what happened in Macedonia with the Bulgarians after WW2: people lived in closed communities - they would often live

in separate villages from mainstream society and would only marry between themselves.

The other issue of the personal names also had to be addressed. A web search of 'Sivrikoz' (that sounds like 'Sevricos') returns a

lot of hits where 'Sivrikoz' is used as a Turkish surname. But Stacy's grandparents' given names were clearly all Christian and Greek. How could that be possible? Could a Greek have taken on a Turkish surname in those troubled times and

places? Most likely, in the same way that people westernise their names to make them more 'likeable' to the general society. The

Sivrikoz name returned only two hits in the Greek telephone directory - but not as 'Sivrikos', only as 'Sivrikozis', a Greekifed form of 'Sivrikoz' by adding the very common ending '-is'. Again,

someone who came to Greece in 1918-1922 with the name 'Sivrikoz' would probably want to sound more Greek than Turkish. Greeks in Turkey at the time may have been coerced into changing their language and surnames but

they were allowed to keep their faith, hence the Christian names, in a similar way to what happened in Macedonia with the Bulgarians after WW2: people lived in closed communities - they would often live

in separate villages from mainstream society and would only marry between themselves.

Stacy's story gave Hrisida a chance to reflect on her own grandmother's origins. "Eastern Thracians don't call themselves Asia Minor refugees (the common Greek translation of 'mikrasiates') because they aren't actually from the shores of Asia Minor, which is south of the Bosporus river. My mum's parents were from a village north of Redestos. A lot of the surnames of Eastern Thracians end in -akis, just like yours."

That did not surprise me in the least. The -άκι (-aki) suffix to Cretan names is a Turkish influence (my own surname, and that of nearly all my relatives ends in -aki, and the ones that don't were originally from Asia Minor refugee stock), used to make a name sound inferior, or simply 'small'. It's a remnant of the former Ottoman rule. In its present Greek usage, it gives a diminutive meaning to a word when added to it, eg 'Maria' becomes 'Maraki' (little Mary), 'paidi' (child) becomes 'paidaki' (little child). Hrisida noted that a local Northern Greek diminutive form (as used in Serres, for example) ends in '-ούδ' (-oud), and is attached to any Greek noun or adjective, eg κουρτσούδ', Μαργούδ', π(ai)δούδ'. This -oύδ' ending is also widely used in Greek Thrace today - yet Hrisida's grandmother's 'co-villagers' preferred to use -άκι, from the Turkish influence of their former homeland.

"There were Cretan policemen in Northern Greece at the time they migrated," Hrisida continued, "and it was said that any name they recorded was written down with the '-akis' suffix, although this is disputable. My grandma used to tell us that they migrated twice to Greece; after the first time, they returned back to their Eastern Thrace village. She was born in 1912 and she was 8 when they migrated to Greece in 1920. They didn't wait for the 'Great Catastrophe' (as the Smyrna 1922 incident is often referred to in Greek history); the signs were already there. First they moved to a very poor barren area in Kilkis, and then to the south of Serres where at least the land was arable.

"I remember seeing old men in the 70s using oxen instead of horses for drawing the carts. That's how I keep my grandma in my mind. Her people are short and stout, fair-haired and blue eyed. They sometimes have strange women's names, like Syrmatenia (wiry), Louloudia (flower), Archontia (noble) and Panorea (beautiful), names we don't hear much at all nowadays. She had it very rough in life. She had eight children, and lost four of them, but she never expressed bitterness and she was always a very kind woman. She never stopped working around the house and she always helped her daughter-in-law, even at the age of 80, which was when she died. The epitome of patience and tolerance, I never heard a bad word from her mouth. My Eastern Thracian relatives lived their lives with dignity and respect for themselves, and people in general. They were mild good-natured people, always polite, smiling and very hospitable; you could always drop by with a group of friends, without giving them any notice, and they would go to great lengths to accommodate your needs. They worked hard and enjoyed their lives. Some of these traits are still noticeable in their children. Although they were an impoverished people, they brought civilisation to the area where they settled. For example, they had curtains in their houses, and a more sophisticated cuisine. Despite being peasants, they had been better educated in their homeland and they sought to educate their children."

Hrisida grew up amongst 'immigrants' from Turkey, like the Pontiacs and Eastern Thracians, Turkish-speaking but Orthodox Karamanlides from Kappadokia, and she used to hear countless stories as a child from other yiayias about how they came to Greece, and the poverty, the struggle, the grief they felt for their lost homeland. "There wasn't much TV in those days to distract us," Hrisida noted. "Even though you have 'mikrasiates' in Crete, you come out as a more uniform society. In Macedonia, every family has an immigrant root. In my grandparents' time, around WW2, there were no mixed marriages between locals and new arrivals, but in the 60s, this slowly changed and I now have aunties who are Eastern Thracians, locals from Serres, a Saracatsan and a Pontiac. The immigrants were Orthodox Christians who always identified themselves as Greek. But these marriages were frowned upon until the 60s."

I knew exactly what Hrisida was talking about. My Cretan mother often spoke about Greek refugees in a condescending tone, something I could never understand and would often reprimand her for doing. This distinction between 'real Greeks' and 'other Greeks' was also apparent in the Greek community of Wellington, as I recall one of the oldest members of the community recounting (while I was interviewing him for my Master's thesis work) what happened in the 50s with the newly arrived Greek-Romanian refugees on the SS Goya. At first they were welcomed as fellow Greeks. But slowly, the differences between the rural Greek-Greeks and the urban Romanian-Greeks came to the fore: one group was obviously more educated, hence more sophisticated, than the other. The community split into two factions: some supported the older more-established Wellington Greek community, while the others joined the newly established Apollo club, the name given to the association created for the welfare and interests of the new arrivals*.

I knew exactly what Hrisida was talking about. My Cretan mother often spoke about Greek refugees in a condescending tone, something I could never understand and would often reprimand her for doing. This distinction between 'real Greeks' and 'other Greeks' was also apparent in the Greek community of Wellington, as I recall one of the oldest members of the community recounting (while I was interviewing him for my Master's thesis work) what happened in the 50s with the newly arrived Greek-Romanian refugees on the SS Goya. At first they were welcomed as fellow Greeks. But slowly, the differences between the rural Greek-Greeks and the urban Romanian-Greeks came to the fore: one group was obviously more educated, hence more sophisticated, than the other. The community split into two factions: some supported the older more-established Wellington Greek community, while the others joined the newly established Apollo club, the name given to the association created for the welfare and interests of the new arrivals*.

This very much summarises the treatment of the Greek Asia Minor refugees when they first arrived in Greece (and vice-versa, meaning the Turks who were forced to leave Greece and return to Turkey, many of whom did not speak Turkish, had been in Greece for many generations and had never thought of Turkey as their home): it is not surprising that many of those immigrants/refugees left Greece and made their way to the West. When they first arrived in Greece, which had become impoverished after the Smyrna catastrophe, they were given inferior land and treated in an inferior manner. Of those who stayed in Northern Greece, they founded new villages wherever they could. Their former homelands were often in the foothills (where firewood was plentiful) near a major spring (with a water source), and not in the middle of a plain where they had no refuge from attacks. These villages may have lacked the character of the typical Greek villages but the personalities of the residents were colourful and vibrant, reminiscent of their struggle for survival in an inhospitable environment. In their newly found villages, they carried on their agricultural work in a more or less similar landscape. Their main problem may have been that they had not been given enough land: up to one hectare for each family, when they may have been raising 4-8 children. Tobacco was often the main crop in Northern Greece because of the good turnover from a small plot of land. Many migrated to Germany and Australia in the 60s.

At this point, Hrisida broke out into a smile. "And with all that

Greekness in us, look at how well our men are doing at dancing the tsifteteli! They

dance the best tsifteteli, not with the belly but with the torso. I've been watching them dancing since I was a child. Children practise it with their

parents at weddings and paniyiria (feasts). My favourite one is the Konyali from Kappadokia, but the same tune was very popular

throughout Asia Minor, Eastern Thrace and the Black Sea region, and there are

different versions of it, which is why I love it so much. It's performed to the same tune as that popular Cypriot song Η βράκα ('The pants')."

After a moment's pause, Hrisida added: "I suppose we can say that Greeks have always been for the paniyiria**, can't we?" We both burst out laughing. "As a whole, I'd say that people in Macedonia and Thrace are more relaxed than the rest of Greece; we're not as restrained. Despite the apparent homogeneity in Greek society we are different in the way we grew up. In Macedonia and Thrace there is no space for arguing what is Greek and what is not. There are so many people with immigrant roots that our culture is a mix and we can't stop enjoying it whether it's called karsilamas or tsifteteli, whether it's burek or pita, whether it's Turkish or Greek."

My marathopites look very similar to the borek Nihal from Turkey (now living in America) makes (left), while stamnagathi and maroulides are similar to dandelion and often cooked with meat in Crete, just like Butel from Turkey (living in the UK) cooks them. The photos from this post come from an older story about Kolotsita.

I certainly got a good history lesson that day from Hrisida. "You live too far away in Crete to be able to keep up to date with Greek history," she said to me, "not to mention the fact that you never went to school in Greece. You were learning only about ancient Greek history, the kind of history Western civilisation associates with Greece." I figured that many of the thigns we discussed together were best kept to ourselves; the last thing we'd want the West to know about us was how heterogeneous we really were, and how inhospitable Greeks could be towards their compatriots, especially at this time when Greece's reputation is already in tatters. But the Greek word for hospitality has an inherent "foreignness" to it: φιλοξενία - filoxenia: 'love of strangers'. Our discussion also showed that Greeks have suffered greater hardships in the past and we still carry inherited memories from those days as we hear stories from the people who had lived them first hand.

Not being able to offer Stacy any direct hospitality, we sent her an email with our combined knowledge, and then headed into our respective kitchens - we were talking via the virtual world and it was time to get back to the real one.

I later asked Hrisida about her grandmother's recipe for the saragli dessert that she used to eat when she was a little girl. "Oh, I don't know it," she replied. "I'll ask my mother if she can remember exactly how yiayia made it. I haven't even eaten it since I was a young girl."

It is easy to lose trace of what we once used to eat since the supermarket culture overtook our lives. At the same time, some of us are more attached to our past, letting it rule our present, while others among us never look back. But while the first generation leaves and the second returns, the third is often left looking for its roots. In a similar sense, the first generation brings their food with them and the second generation eats that food, while the third generation remembers it. Their minds are filled with memories of what they once had; at this point, balance becomes crucial.

The Greek mothers and grandmothers of the past often cooked according to cultural norms, using simple techniques and only a few ingredients. As Hrisida said (above): "All I remember was filo pastry sweetened with syrup. [Gramdma] baked it, maybe with butter, and then just added syrup to it. It sounds so simple, but for us children it was heaven."

"Despite being a slack cook," Hrisida admitted to me later, "I feel strongly about women making their own fyllo because it's a big part of our tradition. If you make pita with ready made filo from the supermarket it tastes like paper. When you resort to that terrible ready-made 'sfoliata' (buttery puff pastry, whose origins are not Greek) for a bit of texture and taste, you lose all the point of a home-made pita. With the rate that young Greek women are resorting to sfoliata, home-made fyllo will be a thing of the past in years to come. Every time I used to see Vefa Alexiadou or her daughter on TV, I'd cringe. That's how women are cooking nowdays, cream, canned mushrooms and melting yellow cheeses, struggling to stretch a ball of dough into fyllo with their thick rolling pin and making it all look so difficult, I'd be thinking 'for God sake's woman, get a yiayia to show you how it's done'. That woman was regarded as an experienced cook! Why on earth are we watching cookshows like that, and even the more modern ones that have followed, when none of that food is even part of our traditional cuisine?"

Vefa, a chemist by profession, was Greece's answer to Delia Smith; in her last TV appearances she used to warn how bad margarine is and recommended butter where necessary. The joke was that she never managed to get a whole fyllo off the counter top and onto the baking tray in one piece.

I happened to have a few balls of pastry left over from my most recent filo-making session. Fresh dough keeps happily in the fridge for a few days. I hadn't prepared any filling, so it sounded like the perfect opportunity to recreate Hrisida's grandma's memorable and heavenly 'saragli'. I asked Hrisida for some more directions: could I recreate an Eastern Thrace delicacy, which was last eaten (possibly) 40 years ago, in my home kitchen in Crete - and all via distance learning? Here are the directions that Hrisida gave me:

"You roll out the fyllo, oil it and then crease it in the baking tray concertina-style, much like we do in patsavouropita. So you don't roll the fyllo to put it in the baking tray, but crease it instead. Then you bake it and when you take it out, you pour syrup over it, like for galaktoboureko or baklava. Of course it is much simpler than patsavouropita. But I have never made my grandmas' pita myself."

I showed Hrisida the photos of my pita: "Oh, it looks great!! So similar to what we used to eat as children. The simple tastes are so heart-warming sometimes. Thank you for reminding me of my grandma. I thought about telling you to sprinkle chopped nuts over the top, but no need, as I see." I am very much a novice at filo/pie making, and I am learning by mistakes - but at least I'm trying not to repeat my mistakes, unlike the Greek politicians, who have created a global quagmire!

We were also both in for a surprise that night: when we checked our email, sure enough, there was one for each of us from Stacy:

If you think you know how to help Stacy find her roots, send me an email.

*This distinction no longer exists, as often happens in immigrant groups that successfully establish themselves in Western cultures.

** για τα πανηγύρια = for the paniyiria, ie crazy, feast-loving people

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

"You use a thick rolling pin to roll out your filo pastry?" My friend sounded surprised. I explained to her that I had gotten used to using this kind of rolling pin and found it trying on my palms to use a thin one.

"That's because you're not using it properly," Hrisida scolded me. "I use a thick rolling pin for the pizza pastry where I only stretch the dough. But for making a pita, you do need the thin one. You're supposed to roll the fyllo and press lightly from the centre outwardly to the ends. It's actually less physical effort than stretching constantly but you need the right tool and a bigger surface area to work. By stretching you can only reach a certain thickness. Even you know that, don't you?" Her voice then softened. "My grandma's rolling pin is very thin and very long. But you can't get one like this now. These days they're much shorter, because we make smaller pies.Our sini are smaller than what my grandmother had." The σινί (sini) is a large baking tray 60cm in diameter with low sides. "We do have a couple that she used to own lying in the storage space in our village home. But people still use them even now - you can see them in bougatsa shops."

"Is your grandmother still alive?" I asked her.

"No, no," she said, shaking her head. "She died a very long time ago." Even though she was smiling, Hrisida's face took on a dull tone, as if it had lost its colour. "My mother's mother was from Eastern Thrace. That's part of Turkey now. She made a lot of pitas. I was a bad eater as a child but I loved her pitas. They were chunky and very filling." He face suddenly lit up. "She also used to make a sweet pitta where she just rolled out the fyllo and then placed it in a circle in the baking tray. My grandma used to call it saragli but it had no filling or topping. All I remember was filo pastry sweetened with syrup. She baked it, maybe with butter and then just added syrup to it. It sounds so simple but for us children it was heaven. And it's strange, but I've never tasted it since then. Not from my mum, nor from my aunties who were very close to my grandma.

Saragli can be filled and rolled up in many different ways, allowing for greater creativity on the part of the cook and a splendid looking array of sweet delicacies for the eater. The ones depicted are home-made with store-bought filo pastry, which is sturdier and drier than home-made pastry, and can therefore be moulded more easily to keep its shape.

As Hrisida told me about her grandmother's story, I was conjuring up the images she was describing: an old woman, dressed in black, with a never-fading smile on her face, her back bent over, her pace quick but short. She would shuffle around her kitchen, preparing food for everyone, and never complain. If anyone told her to take it easy, she'd tell them she wasn't tired. I wondered what her life was like in Eastern Thrace before she came to Greece.

Hrisida's grandmother reminded me of Stacy Costas Dunn, a third generation Greek in the US who had recently contacted me about trying to track down her dead grandparents' hometown so that she could trace her roots and hopefully bring her American-born mother back to them on a holiday. Stacy had given me the names of the villages that were listed on the documents her grandfather was given when they arrived in Ellis Island: 'Kastaboli' (now Ormanli, meaning 'forest' in Turkish), 'Myriofytou' (now Murefte), 'Ghanochora' (now Gazikoy, possible also Hoskoy) - these were the birthplaces or last known homelands of Stacy's grandfather's family. Stacy remembers her family talking about Thrace (Θράκη). That's all she knew about her grandfather's homeland.

After checking the names of the villages again, I discovered that there was a major earthquake in the area that completely destroyed the villages of her grandparents; this earthquake occurred in the year her grandparents migrated to the US. It was all starting to come together. Persecution of Christians in Turkish-occupied areas was already common in Stacy's grandparents' time, according to the link, but even if her grandparents had stayed on after the earthquake, or had the desire to come back to visit or live in their part of Thrace one day, the area would have changed hands soon after they left anyway. Not only that, but these ancestral villages in Eastern Thrace would now obviously have Turkish names, and their original Greek names would need to be traced back to them, making the search for her roots sound rather like a jigsaw puzzle. The villages concerned are all located in coastal areas on the way from Greece to Constantinople before reaching the former Greek region of Redestos (now called Tekirdag in Turkish); Myriofyto for example is now called Murefte, and Aydinlar used to be Kastritsa, or possibly Kistritsa. Although there is sometimes a discernible link to the original word, it is not immediately noticeable.

Now it's Istanbul, not Constantinople

Every gal in Constantinople

Lives in Istanbul, not Constantinople

So if you've a date in Constantinople

She'll be waiting in Istanbul

Lives in Istanbul, not Constantinople

So if you've a date in Constantinople

She'll be waiting in Istanbul

Why did Constantinople get the works?

That's nobody's business but the Turks'.

That's nobody's business but the Turks'.

When Stacy's grandparents came to the US, as immigrants passing through Ellis Island, they would have suffered the stigma of the foreign-sounding name. Names were also often misspelled at the customs offices, as officials were left in the helpless position of transcribing what they think they heard from the newly-arrived non-English-speaking immigrant's mouth, often writing them incorrectly in official documents, which would have remained unchanged (ie uncorrected). Stacy had two possible names for her grandfather: 'Elias Sevricos' and 'Lee Costas', which, to the uninitiated would look wildly different from one another. Her grandfather was probably baptised 'Elias', which was probably changed to 'Lee' in America, while his surname 'Sevricos' was simply dropped - not only did it sound foreign, but it was also difficult to pronounce (again, to the uninitiated). Instead, he used his middle name, which, according to Greek tradition, is always your father's name: according to his US naturalization papers, his parents were Constantinos Sevricoz and Zafireia ('Sapphire', noted as 'Zafery' on the documents) Paraskeva (written as 'Paroskua'; in Modern Greek, 'eu' is pronounced as 'ev' or 'ef' depending on context, and the 'e' was probably seen as superfluous by the customs official).

When Stacy's grandparents came to the US, as immigrants passing through Ellis Island, they would have suffered the stigma of the foreign-sounding name. Names were also often misspelled at the customs offices, as officials were left in the helpless position of transcribing what they think they heard from the newly-arrived non-English-speaking immigrant's mouth, often writing them incorrectly in official documents, which would have remained unchanged (ie uncorrected). Stacy had two possible names for her grandfather: 'Elias Sevricos' and 'Lee Costas', which, to the uninitiated would look wildly different from one another. Her grandfather was probably baptised 'Elias', which was probably changed to 'Lee' in America, while his surname 'Sevricos' was simply dropped - not only did it sound foreign, but it was also difficult to pronounce (again, to the uninitiated). Instead, he used his middle name, which, according to Greek tradition, is always your father's name: according to his US naturalization papers, his parents were Constantinos Sevricoz and Zafireia ('Sapphire', noted as 'Zafery' on the documents) Paraskeva (written as 'Paroskua'; in Modern Greek, 'eu' is pronounced as 'ev' or 'ef' depending on context, and the 'e' was probably seen as superfluous by the customs official).I recounted Stacy's plight to Hrisida. She agreed that the family's names had undergone an Americanised transformation, which was hindering Stacy from finding her roots. 'Zafiris' is a common Thracian name for men ('Zafireia' is the female variant of the same name). 'Myriofyto' is a village in the region of Kilkis in modern-day Greece, where many former Eastern Thracians settled after leaving their homelands. Interestingly, when we looked up the name 'Sivrikos' in the phone book, nothing came up, unlike for 'Paraskevas' which is relatively more common. If Paraskevas could be associated with the villages names of Kastaboli/Myriofytou, some connection pointing Stacy in the right direction could be made. Hrisida suggested some organisations in Northern Greece which look after the interests of people with roots in Eastern Thrace, like the Thrakiki Estia of Serres. Since we live in a more transparent and connected world, people can now also find the former Greek villages in Eastern Thrace and compare them with the Turkish villages in Google Earth.

The other issue of the personal names also had to be addressed. A web search of 'Sivrikoz' (that sounds like 'Sevricos') returns a

lot of hits where 'Sivrikoz' is used as a Turkish surname. But Stacy's grandparents' given names were clearly all Christian and Greek. How could that be possible? Could a Greek have taken on a Turkish surname in those troubled times and

places? Most likely, in the same way that people westernise their names to make them more 'likeable' to the general society. The

Sivrikoz name returned only two hits in the Greek telephone directory - but not as 'Sivrikos', only as 'Sivrikozis', a Greekifed form of 'Sivrikoz' by adding the very common ending '-is'. Again,

someone who came to Greece in 1918-1922 with the name 'Sivrikoz' would probably want to sound more Greek than Turkish. Greeks in Turkey at the time may have been coerced into changing their language and surnames but

they were allowed to keep their faith, hence the Christian names, in a similar way to what happened in Macedonia with the Bulgarians after WW2: people lived in closed communities - they would often live

in separate villages from mainstream society and would only marry between themselves.

The other issue of the personal names also had to be addressed. A web search of 'Sivrikoz' (that sounds like 'Sevricos') returns a

lot of hits where 'Sivrikoz' is used as a Turkish surname. But Stacy's grandparents' given names were clearly all Christian and Greek. How could that be possible? Could a Greek have taken on a Turkish surname in those troubled times and

places? Most likely, in the same way that people westernise their names to make them more 'likeable' to the general society. The

Sivrikoz name returned only two hits in the Greek telephone directory - but not as 'Sivrikos', only as 'Sivrikozis', a Greekifed form of 'Sivrikoz' by adding the very common ending '-is'. Again,

someone who came to Greece in 1918-1922 with the name 'Sivrikoz' would probably want to sound more Greek than Turkish. Greeks in Turkey at the time may have been coerced into changing their language and surnames but

they were allowed to keep their faith, hence the Christian names, in a similar way to what happened in Macedonia with the Bulgarians after WW2: people lived in closed communities - they would often live

in separate villages from mainstream society and would only marry between themselves.Stacy's story gave Hrisida a chance to reflect on her own grandmother's origins. "Eastern Thracians don't call themselves Asia Minor refugees (the common Greek translation of 'mikrasiates') because they aren't actually from the shores of Asia Minor, which is south of the Bosporus river. My mum's parents were from a village north of Redestos. A lot of the surnames of Eastern Thracians end in -akis, just like yours."

That did not surprise me in the least. The -άκι (-aki) suffix to Cretan names is a Turkish influence (my own surname, and that of nearly all my relatives ends in -aki, and the ones that don't were originally from Asia Minor refugee stock), used to make a name sound inferior, or simply 'small'. It's a remnant of the former Ottoman rule. In its present Greek usage, it gives a diminutive meaning to a word when added to it, eg 'Maria' becomes 'Maraki' (little Mary), 'paidi' (child) becomes 'paidaki' (little child). Hrisida noted that a local Northern Greek diminutive form (as used in Serres, for example) ends in '-ούδ' (-oud), and is attached to any Greek noun or adjective, eg κουρτσούδ', Μαργούδ', π(ai)δούδ'. This -oύδ' ending is also widely used in Greek Thrace today - yet Hrisida's grandmother's 'co-villagers' preferred to use -άκι, from the Turkish influence of their former homeland.

"There were Cretan policemen in Northern Greece at the time they migrated," Hrisida continued, "and it was said that any name they recorded was written down with the '-akis' suffix, although this is disputable. My grandma used to tell us that they migrated twice to Greece; after the first time, they returned back to their Eastern Thrace village. She was born in 1912 and she was 8 when they migrated to Greece in 1920. They didn't wait for the 'Great Catastrophe' (as the Smyrna 1922 incident is often referred to in Greek history); the signs were already there. First they moved to a very poor barren area in Kilkis, and then to the south of Serres where at least the land was arable.

"I remember seeing old men in the 70s using oxen instead of horses for drawing the carts. That's how I keep my grandma in my mind. Her people are short and stout, fair-haired and blue eyed. They sometimes have strange women's names, like Syrmatenia (wiry), Louloudia (flower), Archontia (noble) and Panorea (beautiful), names we don't hear much at all nowadays. She had it very rough in life. She had eight children, and lost four of them, but she never expressed bitterness and she was always a very kind woman. She never stopped working around the house and she always helped her daughter-in-law, even at the age of 80, which was when she died. The epitome of patience and tolerance, I never heard a bad word from her mouth. My Eastern Thracian relatives lived their lives with dignity and respect for themselves, and people in general. They were mild good-natured people, always polite, smiling and very hospitable; you could always drop by with a group of friends, without giving them any notice, and they would go to great lengths to accommodate your needs. They worked hard and enjoyed their lives. Some of these traits are still noticeable in their children. Although they were an impoverished people, they brought civilisation to the area where they settled. For example, they had curtains in their houses, and a more sophisticated cuisine. Despite being peasants, they had been better educated in their homeland and they sought to educate their children."

Hrisida grew up amongst 'immigrants' from Turkey, like the Pontiacs and Eastern Thracians, Turkish-speaking but Orthodox Karamanlides from Kappadokia, and she used to hear countless stories as a child from other yiayias about how they came to Greece, and the poverty, the struggle, the grief they felt for their lost homeland. "There wasn't much TV in those days to distract us," Hrisida noted. "Even though you have 'mikrasiates' in Crete, you come out as a more uniform society. In Macedonia, every family has an immigrant root. In my grandparents' time, around WW2, there were no mixed marriages between locals and new arrivals, but in the 60s, this slowly changed and I now have aunties who are Eastern Thracians, locals from Serres, a Saracatsan and a Pontiac. The immigrants were Orthodox Christians who always identified themselves as Greek. But these marriages were frowned upon until the 60s."

I knew exactly what Hrisida was talking about. My Cretan mother often spoke about Greek refugees in a condescending tone, something I could never understand and would often reprimand her for doing. This distinction between 'real Greeks' and 'other Greeks' was also apparent in the Greek community of Wellington, as I recall one of the oldest members of the community recounting (while I was interviewing him for my Master's thesis work) what happened in the 50s with the newly arrived Greek-Romanian refugees on the SS Goya. At first they were welcomed as fellow Greeks. But slowly, the differences between the rural Greek-Greeks and the urban Romanian-Greeks came to the fore: one group was obviously more educated, hence more sophisticated, than the other. The community split into two factions: some supported the older more-established Wellington Greek community, while the others joined the newly established Apollo club, the name given to the association created for the welfare and interests of the new arrivals*.

I knew exactly what Hrisida was talking about. My Cretan mother often spoke about Greek refugees in a condescending tone, something I could never understand and would often reprimand her for doing. This distinction between 'real Greeks' and 'other Greeks' was also apparent in the Greek community of Wellington, as I recall one of the oldest members of the community recounting (while I was interviewing him for my Master's thesis work) what happened in the 50s with the newly arrived Greek-Romanian refugees on the SS Goya. At first they were welcomed as fellow Greeks. But slowly, the differences between the rural Greek-Greeks and the urban Romanian-Greeks came to the fore: one group was obviously more educated, hence more sophisticated, than the other. The community split into two factions: some supported the older more-established Wellington Greek community, while the others joined the newly established Apollo club, the name given to the association created for the welfare and interests of the new arrivals*.This very much summarises the treatment of the Greek Asia Minor refugees when they first arrived in Greece (and vice-versa, meaning the Turks who were forced to leave Greece and return to Turkey, many of whom did not speak Turkish, had been in Greece for many generations and had never thought of Turkey as their home): it is not surprising that many of those immigrants/refugees left Greece and made their way to the West. When they first arrived in Greece, which had become impoverished after the Smyrna catastrophe, they were given inferior land and treated in an inferior manner. Of those who stayed in Northern Greece, they founded new villages wherever they could. Their former homelands were often in the foothills (where firewood was plentiful) near a major spring (with a water source), and not in the middle of a plain where they had no refuge from attacks. These villages may have lacked the character of the typical Greek villages but the personalities of the residents were colourful and vibrant, reminiscent of their struggle for survival in an inhospitable environment. In their newly found villages, they carried on their agricultural work in a more or less similar landscape. Their main problem may have been that they had not been given enough land: up to one hectare for each family, when they may have been raising 4-8 children. Tobacco was often the main crop in Northern Greece because of the good turnover from a small plot of land. Many migrated to Germany and Australia in the 60s.

Οι Έλληνες ήταν, είναι και θα έιναι πάντα για τα πανηγύρια**...

After a moment's pause, Hrisida added: "I suppose we can say that Greeks have always been for the paniyiria**, can't we?" We both burst out laughing. "As a whole, I'd say that people in Macedonia and Thrace are more relaxed than the rest of Greece; we're not as restrained. Despite the apparent homogeneity in Greek society we are different in the way we grew up. In Macedonia and Thrace there is no space for arguing what is Greek and what is not. There are so many people with immigrant roots that our culture is a mix and we can't stop enjoying it whether it's called karsilamas or tsifteteli, whether it's burek or pita, whether it's Turkish or Greek."

My marathopites look very similar to the borek Nihal from Turkey (now living in America) makes (left), while stamnagathi and maroulides are similar to dandelion and often cooked with meat in Crete, just like Butel from Turkey (living in the UK) cooks them. The photos from this post come from an older story about Kolotsita.

I certainly got a good history lesson that day from Hrisida. "You live too far away in Crete to be able to keep up to date with Greek history," she said to me, "not to mention the fact that you never went to school in Greece. You were learning only about ancient Greek history, the kind of history Western civilisation associates with Greece." I figured that many of the thigns we discussed together were best kept to ourselves; the last thing we'd want the West to know about us was how heterogeneous we really were, and how inhospitable Greeks could be towards their compatriots, especially at this time when Greece's reputation is already in tatters. But the Greek word for hospitality has an inherent "foreignness" to it: φιλοξενία - filoxenia: 'love of strangers'. Our discussion also showed that Greeks have suffered greater hardships in the past and we still carry inherited memories from those days as we hear stories from the people who had lived them first hand.

Not being able to offer Stacy any direct hospitality, we sent her an email with our combined knowledge, and then headed into our respective kitchens - we were talking via the virtual world and it was time to get back to the real one.

*** *** ***

I later asked Hrisida about her grandmother's recipe for the saragli dessert that she used to eat when she was a little girl. "Oh, I don't know it," she replied. "I'll ask my mother if she can remember exactly how yiayia made it. I haven't even eaten it since I was a young girl."

It is easy to lose trace of what we once used to eat since the supermarket culture overtook our lives. At the same time, some of us are more attached to our past, letting it rule our present, while others among us never look back. But while the first generation leaves and the second returns, the third is often left looking for its roots. In a similar sense, the first generation brings their food with them and the second generation eats that food, while the third generation remembers it. Their minds are filled with memories of what they once had; at this point, balance becomes crucial.

The Greek mothers and grandmothers of the past often cooked according to cultural norms, using simple techniques and only a few ingredients. As Hrisida said (above): "All I remember was filo pastry sweetened with syrup. [Gramdma] baked it, maybe with butter, and then just added syrup to it. It sounds so simple, but for us children it was heaven."

Hrisida says she is a slack cook, but these are the kinds of pita she makes - that's all home-made filo...

"Despite being a slack cook," Hrisida admitted to me later, "I feel strongly about women making their own fyllo because it's a big part of our tradition. If you make pita with ready made filo from the supermarket it tastes like paper. When you resort to that terrible ready-made 'sfoliata' (buttery puff pastry, whose origins are not Greek) for a bit of texture and taste, you lose all the point of a home-made pita. With the rate that young Greek women are resorting to sfoliata, home-made fyllo will be a thing of the past in years to come. Every time I used to see Vefa Alexiadou or her daughter on TV, I'd cringe. That's how women are cooking nowdays, cream, canned mushrooms and melting yellow cheeses, struggling to stretch a ball of dough into fyllo with their thick rolling pin and making it all look so difficult, I'd be thinking 'for God sake's woman, get a yiayia to show you how it's done'. That woman was regarded as an experienced cook! Why on earth are we watching cookshows like that, and even the more modern ones that have followed, when none of that food is even part of our traditional cuisine?"

Vefa, a chemist by profession, was Greece's answer to Delia Smith; in her last TV appearances she used to warn how bad margarine is and recommended butter where necessary. The joke was that she never managed to get a whole fyllo off the counter top and onto the baking tray in one piece.

I happened to have a few balls of pastry left over from my most recent filo-making session. Fresh dough keeps happily in the fridge for a few days. I hadn't prepared any filling, so it sounded like the perfect opportunity to recreate Hrisida's grandma's memorable and heavenly 'saragli'. I asked Hrisida for some more directions: could I recreate an Eastern Thrace delicacy, which was last eaten (possibly) 40 years ago, in my home kitchen in Crete - and all via distance learning? Here are the directions that Hrisida gave me:

"You roll out the fyllo, oil it and then crease it in the baking tray concertina-style, much like we do in patsavouropita. So you don't roll the fyllo to put it in the baking tray, but crease it instead. Then you bake it and when you take it out, you pour syrup over it, like for galaktoboureko or baklava. Of course it is much simpler than patsavouropita. But I have never made my grandmas' pita myself."

It doesn't matter how scrappily you roll out filo pastry - it's going to break up once you start eating it anyway. I creased the pastry on the table before placing it in the baking tin because home-made filo is softer than store-bought filo, making it stickier to work with. The saragli design traditionally involves rounds of pastry all neatly fitted into a (preferably round) baking tin (to allow for even browning and avoid burnt or over-cooked corners). You may wonder why there's a hole in the middle of the baked pie - I ran out of filo! When the filo had turned golden, as soon as it came out of the oven, I poured a freshly made (but cooled)

boiled sugar-water syrup over it (perfumed with a wedge of lemon and some fir-tree honey from Karpenisi that Hrisida had given me as a gift). I also

sprinkled some chopped walnuts over it just to make it look more

'interesting'; this saragli reminded me of xerotigana, a very popular Cretan

fried pastry made on festive occassions, which is also doused in syrup and topped with grated walnuts.

I showed Hrisida the photos of my pita: "Oh, it looks great!! So similar to what we used to eat as children. The simple tastes are so heart-warming sometimes. Thank you for reminding me of my grandma. I thought about telling you to sprinkle chopped nuts over the top, but no need, as I see." I am very much a novice at filo/pie making, and I am learning by mistakes - but at least I'm trying not to repeat my mistakes, unlike the Greek politicians, who have created a global quagmire!

We were also both in for a surprise that night: when we checked our email, sure enough, there was one for each of us from Stacy:

"It is so nice to hear from you. I think of you often as you were one of the first people I reached out to when I started this quest. At the time, I thought to myself, "Greeks are such congenial people! So kind and helpful!" You helped and inspired me so much last year to keep searching, even though it often felt like I was chasing my tail. Your friend is right about the brick wall when it comes to the Sevricos name. I've been looking into various spellings: Safricas, Savaricas, and even Tsivrikos. I've taken to looking into my great grandmother's name, Paraskevas, as I feel there's more chance in making a connection. From genealogy.com, I found out there was a Paraskevas family in Saranta Ekklisies (now called Kirklareli in Turkey), near Edirne (formerly Adrianoupoli). A Helen Paraskevas was a teacher there, about 1920. A photographer was called K. Zafiriadis. A Paraskevas went to school in 1916 in Saranta Ekklisies. He later migrated to Grenoble in France where he married a French woman there.

It does sound hopeful, but my biggest problem is the language barrier. I can't thank you enough for keeping me in mind and passing my information on to someone that might be able to help. I will keep searching and hoping for some answers. My Greek heritage means so much to me. Thank you again for your time and consideration!"It also meant a lot to me and Hrisida that we could offer our own form of filoxenia - hospitality - to a fellow Greek like Stacy so many thousands of miles away from Greece, by providing as much help as possible in her search for her roots. As I ate a piece of the saragli later in the evening, I wondered if Stacy's grandmother had also cooked a tasty treat just like this one, just like Hrisida's grandma did, creating memories of her that lived on well after she had left the mortal world.

If you think you know how to help Stacy find her roots, send me an email.

*This distinction no longer exists, as often happens in immigrant groups that successfully establish themselves in Western cultures.

** για τα πανηγύρια = for the paniyiria, ie crazy, feast-loving people

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

A truly beautiful story

ReplyDeleteMaria, very good read on where and how some Greek surnames came about. I can see it now: you relating this story around your table and bringing a just-baked pita out of the oven for serving.

ReplyDeleteOnce again you have informed and entertained me!

ReplyDeleteWhen my mother died unexpectedly last New Years Eve I became reacquainted by email with some of my cousins whom I had not seen for more than 40 years. That resulted in my quest to find out more about my mother's past and her family in Norway. It's always fascinating delving into the past. I only wish I had been more curious while my mother was alive. She did not like to discuss the past, though, so rarely volunteered any information. One of my cousins sent me old photos and letters she had saved and all that has been very helpful. I do know that there is a cousin about my age in Norway and maybe some day I will visit him.

It's so good of you to try to help Stacy, Maria.

All of that history is a very tangled web and it makes it so much harder when names were changed, sometimes more than once. And....as always...so fascinating!

your story makes me so sad becos i know what it feels like to be asking questions too late - my parents have both died, and although my aunts and uncles and filled in a great deal of the gaps in my knowledge, it's not the same hearing it straight from your parents' mouths

ReplyDeleteSimply wonderful. One of your best, both the story and the writing.

ReplyDelete