This post continues from a previous post related to food, migration and identity.

Of migration, it is often said that the first generation leaves, the second returns, while the third is left to look for its roots. In a similar sense, the first generation brings their food with them, the second generation seeks their food, while the third generation tries to keep their food memories alive. I was reminded of this recently when a friend of mine who was leaving Greece to return to her homeland gave me a little vial filled with rum essence. "I won't be needing this any more, because I'm going back home", she said. She explained that it's used in Romania to give cakes their characteristic flavour, like we often use vanilla essence or orange zest in Greece. When she originally left her homeland, she carried her food with her. First-generation migrants adapt their food customs to suit the ingredients, technology, preparation time (among other factors) available in their new environment. The second generation often maintains these food customs to a certain degree. The third generation is often left with memories of such food, possibly nurtured by trips to their ancestors’ homeland. Nowadays such needs are catered for by the internet, which has become a powerful marketing tool in the food industry.

What is it with migrants and the way they seek food from their homeland? It isn't that their new environment lacks food - in fact, it probably contains even more variety than they were used to:

In the past, migrants were used to taking their food with them as they moved, in different ways: maybe an ingredient, or a cookbook, some cooking notes, passive knowledge of what they expect of food (ie their memories), or active knowledge of the culinary techniques of their culture (ie they cooked in their homeland). They may have carried ingredients in their suitcases, like my Romanian friend, or simply just kept their food memories in their head, like my mother. The migrant is constantly in search of a sign from home in the new country: his food is just as important as his people, his language, his music and his religion. Globalisation may have created a concept of global food, and in the migrant's case, it's made it easier to keep him/her close to their culinary culture: these days, the ingredients are easier to source, and the internet can make up for lack of technique in the novice cook. But at the same time, the migrant will be heard to say "It's not the same thing" when he eats something in the new country which he thought came from or looked like something he remembered from his homeland: the migrant is constantly in search of the authentic taste, something very hard to find away from the source.

Following your nose can often lead you to where the migrant communities cluster: when you walk in the migrant ghettos of any large town or city, you can smell their food. In the past, when I took my children to after-school activities in the town, I particularly liked to walk in the early evening in the housing area of my town between the central market and the law courts for this reason, because it was a form of restaurant travel - I was transported to foreign places just by the aromas emanating from the kitchens of the homes in this inner-city area. The smells were not Greek. There was a smack of ginger, and a punch of coriander, mingled with a hint of saffron, and a number of other lesser known spices permeating the air. In the same way that the air of those houses was being infiltrated with new sounds of language and music, the walls of those homes were being lined with new aromas. The fluid nature of identity can best be observed in the immigrant behaviour, through their food.

In the same way that it may be difficult to learn to speak another person's language, it may also be difficult to learn to cook/eat another person's cuisine. It's so much easier to simply understand it, in the same way that we try to understand what someone is saying to us in a foreign language, even though we don't speak the language well ourselves. When we try to speak a new language, we make mistakes, often sounding unnatural; above all, experimentation is the norm. That sounds just like what we do when we eat food that is foreign to us, food we don't know. The similarities between language and cuisine are greatly evidenced among migrant communities. But while we can be bilingual, can we really be bi-cuisinal?

Other people's food feels almost like another language; it gets easier to cope with a new cuisine over time. Education plays a major - albeit sometimes subconscious - role, as it creates a positive attitude to other people's food: broadening our horizons means we become more accepting of other people's customs, including their cuisine; we learn to eat - and love - other people's food. Even though we may not be cooking other people's food in our own home (the difference between eating and cooking is similar to the difference between theory and practice), we learn from the multi-faceted experience of something different, with people whose food customs are not the same as ours.

As the migrant generations pass, all that may remain is the memory, often misguided by conflicting sources of information. When the moment comes that we find ourselves speaking that foreign language fluently, or eating that other cuisine as if we had been brought up on it, that's when we realise that maybe we have lost something from our past: the language of our home, just like the home-cooked meals of our mother, may be what we identify with culturally, but in the process of self-realisation, we may also have made them an integral part of our past.

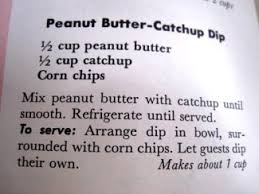

Some cultures like to burp after a meal to show enjoyment, some cultures believe that their guests must never have their plate empty, others are offended when a guest empties their plate before the host: the rules of eating depend to a significant extent on the culture. Cretan table custom dictates that plates must never be taken away from the table when guests are eating, because this signifies that the guests are being asked to leave the host's house! Some cultures prefer using metallic utensils, while others prefer to wash their hands and eat with their fingers. While olive oil and vinegar may be set features of laying a table in Greece, they would like out of place in a Chinese restaurant where one would expect a bottle of soya sauce and a bowl of chili. Similarly, culinary preferences differ among cultures: just like those things that certain people prefer not to talk about, there are some items that certain cultures do not consider a food source. An Athenian once said to me that Cretans eat strange food, like broad beans, artichokes, snails, offal and sea urchins! Some people's food is other people's terror:

The further away migrants find themselves from their main point of food reference, the more food memories they begin to form. There are now more options available to them to help them keep their food memories alive: apart from asking their elders or seeking out the required information from the source, they can search the internet, browse through photos and read blogs. Whether it's a personal quest or simply a case of trying to preserve a family tradition, their memories preserve their identity.

Although Greece is currently in a state of transition, Greek (and more specifically Cretan) cuisine hasn't reached the point where anything goes, as in Western cuisine where rules rarely apply and creativity is seen as more important than tradition, but it has been affected by commerce and trade (notably supermarkets with their loyalty cards and special offers), tourism, convenience food/stores, politics (people buy cheaper food now and less meat - reverting to former habits), nationalism (our identity is under threat after all the bad publicity from the global reporting of the economic crisis), and marketing (Greek food is globally very popular), among other factors. Cretan cuisine, considered to be one of the healthiest diets, with

a focus on the Mediteranean and its emphasis on the use of olive oil,

can benefit from greater exposure with more Greeks abroad, as more and

more people around the world seek it out for its health benefits, making it a very marketable product in our time. It would also be interesting to find out what exactly is being cooked on a daily basis in Cretan homes, crossing all sectors: rural-urban, age, sex, employed or not. It's not uncommon to see taverna menu title stating "Yiayia's cuisine" - if Yiayia is said to be cooking these dishes, then what kind of culinary culture is Mama passing on to her brood?

Although Greece is currently in a state of transition, Greek (and more specifically Cretan) cuisine hasn't reached the point where anything goes, as in Western cuisine where rules rarely apply and creativity is seen as more important than tradition, but it has been affected by commerce and trade (notably supermarkets with their loyalty cards and special offers), tourism, convenience food/stores, politics (people buy cheaper food now and less meat - reverting to former habits), nationalism (our identity is under threat after all the bad publicity from the global reporting of the economic crisis), and marketing (Greek food is globally very popular), among other factors. Cretan cuisine, considered to be one of the healthiest diets, with

a focus on the Mediteranean and its emphasis on the use of olive oil,

can benefit from greater exposure with more Greeks abroad, as more and

more people around the world seek it out for its health benefits, making it a very marketable product in our time. It would also be interesting to find out what exactly is being cooked on a daily basis in Cretan homes, crossing all sectors: rural-urban, age, sex, employed or not. It's not uncommon to see taverna menu title stating "Yiayia's cuisine" - if Yiayia is said to be cooking these dishes, then what kind of culinary culture is Mama passing on to her brood?

Global cuisine and new migration trends in Crete, such as the cases of economic migrants and ‘tourist residents’, have also provided new foodways, manifesting the importance of food as an important element expressing a person’s identity, with the present range of food-related business exchanges (notably the supermarket culture) taking place on the island: in Hania, it is now possible to find more 'ethnic' foods often deemed staples in a more globalised environment than it ever was before. Greeks now migrating abroad due to the economic crisis will probably be astonished to find, in a few years' time (when they come back to visit after 'doing well' abroad), that the food of their country has changed, and will themselves be demanding the 'aunthentic' taste of their food as they remember it! Cuisine isn't really static - it changes according to our needs, our

knowledge, our beliefs, our state of mind, where we find ourselves; in other words, what we eat changes according to our needs, feelings,

desires, outlook and knowledge - and following from that, our identity also undergoes change.

Global cuisine and new migration trends in Crete, such as the cases of economic migrants and ‘tourist residents’, have also provided new foodways, manifesting the importance of food as an important element expressing a person’s identity, with the present range of food-related business exchanges (notably the supermarket culture) taking place on the island: in Hania, it is now possible to find more 'ethnic' foods often deemed staples in a more globalised environment than it ever was before. Greeks now migrating abroad due to the economic crisis will probably be astonished to find, in a few years' time (when they come back to visit after 'doing well' abroad), that the food of their country has changed, and will themselves be demanding the 'aunthentic' taste of their food as they remember it! Cuisine isn't really static - it changes according to our needs, our

knowledge, our beliefs, our state of mind, where we find ourselves; in other words, what we eat changes according to our needs, feelings,

desires, outlook and knowledge - and following from that, our identity also undergoes change.

As people move around the world with a view to finding a place to call home, they keep an ear or an eye out for signs of their former home; their nose often works just as well as their sight and hearing. Food becomes not just a symbol of, but the reality of, love and security. Through tangible reminders of their food - ethnic restaurants and imported supermarket produce, to name but two - they know they will find their own people; it's a cultural safety net, a feeling of comfort to know that you find yourself among your own people. The food that Greek people identify with can tell us a lot about the Greek identity itself; a better analysis of this aspect of Greek identity will no doubt provide a greater insight into the Greek personality (if it can be generalised), and possibly provide workable solutions to the problems plaguing the country at present.

If you liked reading this article, you will probably enjoy Robin Fox's highly entertaining Food and Eating: an Anthropological Perspective.

Of migration, it is often said that the first generation leaves, the second returns, while the third is left to look for its roots. In a similar sense, the first generation brings their food with them, the second generation seeks their food, while the third generation tries to keep their food memories alive. I was reminded of this recently when a friend of mine who was leaving Greece to return to her homeland gave me a little vial filled with rum essence. "I won't be needing this any more, because I'm going back home", she said. She explained that it's used in Romania to give cakes their characteristic flavour, like we often use vanilla essence or orange zest in Greece. When she originally left her homeland, she carried her food with her. First-generation migrants adapt their food customs to suit the ingredients, technology, preparation time (among other factors) available in their new environment. The second generation often maintains these food customs to a certain degree. The third generation is often left with memories of such food, possibly nurtured by trips to their ancestors’ homeland. Nowadays such needs are catered for by the internet, which has become a powerful marketing tool in the food industry.

What is it with migrants and the way they seek food from their homeland? It isn't that their new environment lacks food - in fact, it probably contains even more variety than they were used to:

"...although the whole British colonial system had, in historical terms done a lot of things in different parts of the world barbaric and wrong – there is no doubt that this brought together people of so many different races, cultures and nationalities. I said well, how many in this audience tonight have had a Chinese meal, an Indian takeaway, a Greek or a Hungarian or Italian pizza or whatever, and everybody’s hand went up." (Leon Albert Murray, a Methodist minister, who came to England from Jamaica in the 1950s.)

Greek! (London)

Grec! (Paris)

Migrant housing in Hania

What we eat, how we eat, and when we eat reflect the

complexity of wide cultural arrangements around food and foodways, the unique organization of

food systems, and existing social policies. (Mustafa Koc and Jennifer Welsh, 2002)

complexity of wide cultural arrangements around food and foodways, the unique organization of

food systems, and existing social policies. (Mustafa Koc and Jennifer Welsh, 2002)

Other people's food feels almost like another language; it gets easier to cope with a new cuisine over time. Education plays a major - albeit sometimes subconscious - role, as it creates a positive attitude to other people's food: broadening our horizons means we become more accepting of other people's customs, including their cuisine; we learn to eat - and love - other people's food. Even though we may not be cooking other people's food in our own home (the difference between eating and cooking is similar to the difference between theory and practice), we learn from the multi-faceted experience of something different, with people whose food customs are not the same as ours.

Russian food supplies store in Hania

"All cultures go to considerable lengths to obtain preferred foods, and often ignore valuable food sources close at hand. The English do not eat horse and dog; Mohammedans refuse pork; Jews have a whole litany of forbidden foods (see Leviticus); Americans despise offal; Hindus taboo beef, and so on. People will not just eat anything, whatever the circumstances. In fact, omnivorousness is often treated as a joke. The Chinese are indeed thought by their more fastidious neighbors to eat anything. The Vietnamese used to say that the best way to get rid of the Americans would be to invite in the Chinese, who would surely find them good to eat." (Food and Eating: An Anthropological Perspective, by Robin Fox)

"Ο Κρητικός στη ξενιτειά πόσα λεφτά δε δίδει, να βρει μπουμπουριστούς χοχλιούς να φάει με το ξύδι;"

(How much would a Cretan pay - if he could only track - some fried snails dressed in vinegar - when in a foreign land?)

(How much would a Cretan pay - if he could only track - some fried snails dressed in vinegar - when in a foreign land?)

The further away migrants find themselves from their main point of food reference, the more food memories they begin to form. There are now more options available to them to help them keep their food memories alive: apart from asking their elders or seeking out the required information from the source, they can search the internet, browse through photos and read blogs. Whether it's a personal quest or simply a case of trying to preserve a family tradition, their memories preserve their identity.

My own food memories take me back to New Zealand, to similar window displays in cake shops like this one.

The food of our memories is a keepsake; in the same way that we do not want to lose our memory, we do not want to lose our food. It may be a conscious or sub-conscious reminder of who we are. Our recollections of our food are forced out into the open the further away we find ourselves from the source: the more memories we have of food, the more we fight with our memory to keep those foods alive. Where would the modern food world be without the internet? My blog receives the average hits per day in the days preceding Easter: a Cretan Easter is associated with specific culinary creations: gardoumakia, kalitsounia, kreatotourta. Cretan migrant-families' food memories come alive at this time.

In Food, self and identity, Claude Fischler (1988) argues that identity formation is related to food: it combines two different dimensions, one of which runs from the biological to the cultural (i.e., the nutritional function to the symbolic function), while the other links the individual to the collective (i.e., the psychological to the social). Two aspects of the human relationship to food are stressed: the omnivorous nature of man and its multiple implications, and the process of incorporation and its associated representations. It is argued that omnivorousness implies a fundamental ambivalence, that 'you are what you eat' not only organically, but in terms of beliefs and representations. The more omnivorous people become, and the more accepting they are of cultural norms that are not associated with their own. Being an omnivore is akin to being free of prejudices, among the needs of self-actualisation, the highest ranking in Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. It could be argued that people are more likely to become more omnivorous when living in the western world, but that is another myth: westerners become more attached to technology, which is where they get their food from these days, implying that the formation of an identity - in other words, distinguishing oneself among others - is a primitive need; identity construction is an increasingly important area in consumption theories, consumers choosing products which match their current or aspired personalities.

In Food, self and identity, Claude Fischler (1988) argues that identity formation is related to food: it combines two different dimensions, one of which runs from the biological to the cultural (i.e., the nutritional function to the symbolic function), while the other links the individual to the collective (i.e., the psychological to the social). Two aspects of the human relationship to food are stressed: the omnivorous nature of man and its multiple implications, and the process of incorporation and its associated representations. It is argued that omnivorousness implies a fundamental ambivalence, that 'you are what you eat' not only organically, but in terms of beliefs and representations. The more omnivorous people become, and the more accepting they are of cultural norms that are not associated with their own. Being an omnivore is akin to being free of prejudices, among the needs of self-actualisation, the highest ranking in Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. It could be argued that people are more likely to become more omnivorous when living in the western world, but that is another myth: westerners become more attached to technology, which is where they get their food from these days, implying that the formation of an identity - in other words, distinguishing oneself among others - is a primitive need; identity construction is an increasingly important area in consumption theories, consumers choosing products which match their current or aspired personalities.

Food conveys a common culture in the mish-mash melting-pot world. Love passes through the stomach, we often hear, as it did for Sami, an American-born Iranian, who fell in love with the immigrant Iranian Ziba:

Food conveys a common culture in the mish-mash melting-pot world. Love passes through the stomach, we often hear, as it did for Sami, an American-born Iranian, who fell in love with the immigrant Iranian Ziba:

"As he came to know her... he noticed how much they understood about each other without discussion. A cloak of shared background surrounded them invisibly. She asked him in mid-March if he planned to go home for the next weekend, and she didn't need to explain that she meant for New Year's. He passed her on the library steps where she was eating a snack with a friend, and her snack was not chips or cookies or Ring Dings but a pear, which she was slicing into wedges with a tiny silver knife like the ones his mother set out with the fruit tray after every meal." (Anne Tyler, 2006, Digging to America)Just think what divorce might mean in a bicultural family. One of the saddest memories from my childhood that often comes to my mind is when one of my Eurasian friends' parents got divorced. Her Chinese father used to do all the cooking in her house, but after the divorce, she stayed with her Kiwi mother while her father moved to another town. With the loss of her father's cooking, she felt that she had lost one of her most treasured possessions. Her forced identity transformation would have had serious detrimental effects in her teenage years.

Global cuisine and new migration trends in Crete, such as the cases of economic migrants and ‘tourist residents’, have also provided new foodways, manifesting the importance of food as an important element expressing a person’s identity, with the present range of food-related business exchanges (notably the supermarket culture) taking place on the island: in Hania, it is now possible to find more 'ethnic' foods often deemed staples in a more globalised environment than it ever was before. Greeks now migrating abroad due to the economic crisis will probably be astonished to find, in a few years' time (when they come back to visit after 'doing well' abroad), that the food of their country has changed, and will themselves be demanding the 'aunthentic' taste of their food as they remember it! Cuisine isn't really static - it changes according to our needs, our

knowledge, our beliefs, our state of mind, where we find ourselves; in other words, what we eat changes according to our needs, feelings,

desires, outlook and knowledge - and following from that, our identity also undergoes change.

Global cuisine and new migration trends in Crete, such as the cases of economic migrants and ‘tourist residents’, have also provided new foodways, manifesting the importance of food as an important element expressing a person’s identity, with the present range of food-related business exchanges (notably the supermarket culture) taking place on the island: in Hania, it is now possible to find more 'ethnic' foods often deemed staples in a more globalised environment than it ever was before. Greeks now migrating abroad due to the economic crisis will probably be astonished to find, in a few years' time (when they come back to visit after 'doing well' abroad), that the food of their country has changed, and will themselves be demanding the 'aunthentic' taste of their food as they remember it! Cuisine isn't really static - it changes according to our needs, our

knowledge, our beliefs, our state of mind, where we find ourselves; in other words, what we eat changes according to our needs, feelings,

desires, outlook and knowledge - and following from that, our identity also undergoes change. As people move around the world with a view to finding a place to call home, they keep an ear or an eye out for signs of their former home; their nose often works just as well as their sight and hearing. Food becomes not just a symbol of, but the reality of, love and security. Through tangible reminders of their food - ethnic restaurants and imported supermarket produce, to name but two - they know they will find their own people; it's a cultural safety net, a feeling of comfort to know that you find yourself among your own people. The food that Greek people identify with can tell us a lot about the Greek identity itself; a better analysis of this aspect of Greek identity will no doubt provide a greater insight into the Greek personality (if it can be generalised), and possibly provide workable solutions to the problems plaguing the country at present.

If you liked reading this article, you will probably enjoy Robin Fox's highly entertaining Food and Eating: an Anthropological Perspective.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

Maria, you've done it again! That was a very interesting and informative post. Aside from what I've read on your blog, here is my total knowledge of Greek food.

ReplyDeleteMany years ago there was a "Greek" restaurant in Vail, where I lived at the times. It was called "Kostas." As you can imagine, it was very popular. I remember going there with my new boy friend (and now he's my dear hubby) after our shifts at a French restaurant. There would be dozens of people dancing to the music of the bozouki and lots of drinking of ouzo or retsina. One dish I loved was "pastitzio." After maybe about 10 years of extreme popularity the

restaurant folded. That is my total experience with Greek food.

My grandparents came from Norway around 1890 to 1915. Growing up, and while we were still living around our aunts and uncles and grandparents we ate lots of Norwegian dishes. Then our dad moved us to Colorado and all that completely stopped. My mother was not a very interested or resourceful cook. We soon were introduced to Mexican food. That is my true love now. I have lots of Mexican friends and lots to learn from the mamas. I love to visit their homes and watch and help the moms and sisters as they cook together. I could eat Mexican dishes every day!

I am going to look for the book you mentioned. Since starting to read lots of wonderful blogs and food books my food knowledge has increased a lot. What we eat and why we eat it is a fascinating topic, I think.

Thanks for your interesting posts.

like you caterina, i have a love of foregin food, and have learnt so much from a friend who sent me some asian seeds - we are totally sold on chinese food in our house, even though we dont have affordable chinese restaurants in the town and we can only buy bottled imported ingredients!

ReplyDelete