This post is the third of a series that have been written specifically for the Hellenic New Zealand Congress, which will be holding a conference some time next year.

For the previous part, click here.

In total, 91 people were interviewed, close to the mark of 100, which was thought to be representative of a community of 2,500 people given the time-frame I was given to complete the study (I had to collect and analyse the date, as well as write the thesis in the space of a year). Of the people chosen through the random sample to be interviewed, some people knew me (and they all agreed to participate), I introduced myself as a friend of a friend to some others (and got 85% participation from them), while others were not known to me (I got 30% participation from them). As you can see, it pays to be an insider...

The results of the survey were not surprising:

although there was a high degree of language maintenance among the

sample, it was found that with each succeeding generation, Greek

language proficiency decreased. Older people had better Greek skills

overall, but which generation people belonged to was the only

significant variable that could predict Greek language maintenance - in

other words, the later the generation, the lower the Greek language

skills.

Positive but insignificant differences were found among males and females (females used Greek more often than males when speaking to children, even in cases of intermarriage), different occupations, participation in Greek-related events, attending Greek church regularly (the church environment is seen as an appropriate setting for speaking Greek), making return journeys to Greece/Cyprus, attending after-hours Greek school classes, living near other Greek people, and/or having predominantly monolingual parents and/or grandparents.

The later the generation, the less likely the subject will speak Greek with their family members. The Greek language was mainly used when speaking to older family members. The results showed a clear shift towards the use of English for each succeeding generation. Between the same generations, the same language was used: the first generation used Greek, while later generations used English. At the same time, there is a tendency for the young age groups in the second generation to use Greek to their children, suggesting that there is a greater awareness of language maintenance in this group and that more Greek may be spoken to children when they are young.

Apart from the fact that a conscious awareness was evident in the second generation to pass on tthe Greek language to their children, the

results generally do not bode well for the maintenance of the Greek language among

the community members in Wellington, as is to be expected, given that

linguistic and cultural assimilation is deemed inevitable. But the

findings of the survey also revealed some very positive attitudes

towards the Greek language and culture. The less

one is competent in Greek, the less one feels it to be a core value for

Greek identity. But with each succeeding generation, there is:

So as competence decreases, the perceived need for the Greek language in New Zealand increases. Anecdotal evidence also suggested that respondents also saw the usefulness of knowing Greek for returning to Greece and having a private conversation in a public place. The Greek language was also seen as having cultural and educational value, as well as an identity marker. But knowing the Greek language was not deemed a status marker in the group - knowledge of the Greek language was a clear sign of the generation of Greek New Zealander that one belonged. Hence, Greek does not carry a 'status' in the Greek community of Wellington, therefore it will be harder to maintain the language as it does not serve a particular purpose.

It should be noted that language competence can be

judged by the language one uses to count with, write their shopping

notes, swear, pray and when in danger. If these functions are generally

performed in Greek, then the Greek language is dominant; if these

functions are generally performed in English, then Greek is not

dominant. Although many respondents mentioned that they used both

languages in these circumstances, later generations claimed to use Greek less

often.

In terms of Greek language maintenance, a few things do help: visits to Greece or Cyprus help maintain links with Greek language and culture, participation in Greek-related activities is useful as it provides exposure to the language and culture, and the importance of using Greek in the home should not be underestimated. Hence, language maintenance is both a societal and an individual phenomenon.

A few other non-linguistic comments made by the respondents are also worth noting:

- what it means to be a New Zealander, as opposed to being a Greek,

- whether it is possible to be a Kiwi when you also call yourself a Greek,

- traditional Greek attitudes must make way somehow for more modern thinking to suit the environment of New Zealand Greeks,

- the Greek Orthodox church must make some modifications if it wishes to remain an established church in New Zealand (eg use English in the services).

These points all underlie a conscious idea of identity. Specific mention of the Greek identity in the first two points shows that they are in conflict. Mention of culturally-specific attitudes in the third point shows that people realise that some Greek attitudes are not harmonious with the Kiwi lifestyle. Concerning the language used in the Greek Orthodox church, as mentioned in the fourth point, English is now also used in some parts of the service (it wasn't when I was living there!) although the last time I was in New Zealand (2004), I noticed an absence of young people attending Sunday church services.

Greeks in New Zealand are generally well-integrated members of mainstream Kiwi society. This shows to what extent their establishment in New Zealand is successful. But even in my days, there were some Greeks (like myself) whose visit to the homeland took on a more permanent form.

In the next part of this discussion, I discuss identity conflict - what happens when immigrants and/or their children, who were born and/or raised in the New World, do not fit into mainstream society?

If you are interested in language/cultural studies, you may also want to read the following:

- English language examinations in Greece

- Primary school education in Greece

- The role of the Greek Orthodox church in the diaspora

You can find more of my writing about identity and New Zealand throughout my blog.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

For the previous part, click here.

GREEK LANGUAGE MAINTENANCE IN THE GREEK COMMUNITY OF WELLINGTON, NZ

From

the combined lists of membership in Greek special-interest groups in the Greek community of Wellington, I chose a

random sample of 64 households whose members were tested on their Greek and English language skills through a

questionnaire asking people about their Greek language use (this project formed the basis of my Master's degree). Where

possible, all members of the household were interviewed, in an attempt

to include an equal number of subjects to represent age, sex and

birthplace. The latter was very important - it was necessary to

interview Greek people born in New Zealand in order to ascertain Greek

language maintenance past the first generation.In total, 91 people were interviewed, close to the mark of 100, which was thought to be representative of a community of 2,500 people given the time-frame I was given to complete the study (I had to collect and analyse the date, as well as write the thesis in the space of a year). Of the people chosen through the random sample to be interviewed, some people knew me (and they all agreed to participate), I introduced myself as a friend of a friend to some others (and got 85% participation from them), while others were not known to me (I got 30% participation from them). As you can see, it pays to be an insider...

The steps in the process of my study, with a proposed time-frame for interviewing the subjects.

Positive but insignificant differences were found among males and females (females used Greek more often than males when speaking to children, even in cases of intermarriage), different occupations, participation in Greek-related events, attending Greek church regularly (the church environment is seen as an appropriate setting for speaking Greek), making return journeys to Greece/Cyprus, attending after-hours Greek school classes, living near other Greek people, and/or having predominantly monolingual parents and/or grandparents.

The later the generation, the less likely the subject will speak Greek with their family members. The Greek language was mainly used when speaking to older family members. The results showed a clear shift towards the use of English for each succeeding generation. Between the same generations, the same language was used: the first generation used Greek, while later generations used English. At the same time, there is a tendency for the young age groups in the second generation to use Greek to their children, suggesting that there is a greater awareness of language maintenance in this group and that more Greek may be spoken to children when they are young.

It has been over 20 years that I conducted my anonymous survey. I

diligently kept all my notes of the people that took part in my survey.

The names of these people carry great meaning for many Greeks who were

born or raised in Wellington. Some names remain in the community, while

others have been lost, due to death, intermarriage or departure of the family.

After 20 years, I believe I am not harming anyone in revealing the names

of those people who took part in my study; as a tribute to them, I have

made this tag cloud (and I can now throw away all those old-fashioned

computer printouts with the holes on the sides that have yellowed with

age).

- a more strongly expressed belief in the need for the Greek language in New Zealand,

- more desire to maintain the Greek culture in New Zealand, and

- more desire to be recognised as a Greek New Zealander.

So as competence decreases, the perceived need for the Greek language in New Zealand increases. Anecdotal evidence also suggested that respondents also saw the usefulness of knowing Greek for returning to Greece and having a private conversation in a public place. The Greek language was also seen as having cultural and educational value, as well as an identity marker. But knowing the Greek language was not deemed a status marker in the group - knowledge of the Greek language was a clear sign of the generation of Greek New Zealander that one belonged. Hence, Greek does not carry a 'status' in the Greek community of Wellington, therefore it will be harder to maintain the language as it does not serve a particular purpose.

The above table (split over two pages) tells us that most of the respondents were from the second generation of immigrants (including the 1b category - they were born in outside of New Zealand, but they came to New Zealand before secondary school age), more than half were under 50 years of age, and of those that were married, their spouses were also Greek. The inherent bias in the study which could not be rectified was that intermarried non-community oriented members could not be included in the study.

In terms of Greek language maintenance, a few things do help: visits to Greece or Cyprus help maintain links with Greek language and culture, participation in Greek-related activities is useful as it provides exposure to the language and culture, and the importance of using Greek in the home should not be underestimated. Hence, language maintenance is both a societal and an individual phenomenon.

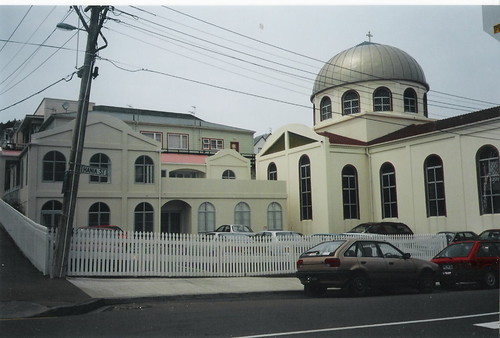

The Greek Orthodox church of Wellington, located on the street renamed Hania St, in Mt Victoria.

- what it means to be a New Zealander, as opposed to being a Greek,

- whether it is possible to be a Kiwi when you also call yourself a Greek,

- traditional Greek attitudes must make way somehow for more modern thinking to suit the environment of New Zealand Greeks,

- the Greek Orthodox church must make some modifications if it wishes to remain an established church in New Zealand (eg use English in the services).

These points all underlie a conscious idea of identity. Specific mention of the Greek identity in the first two points shows that they are in conflict. Mention of culturally-specific attitudes in the third point shows that people realise that some Greek attitudes are not harmonious with the Kiwi lifestyle. Concerning the language used in the Greek Orthodox church, as mentioned in the fourth point, English is now also used in some parts of the service (it wasn't when I was living there!) although the last time I was in New Zealand (2004), I noticed an absence of young people attending Sunday church services.

Greeks in New Zealand are generally well-integrated members of mainstream Kiwi society. This shows to what extent their establishment in New Zealand is successful. But even in my days, there were some Greeks (like myself) whose visit to the homeland took on a more permanent form.

In the next part of this discussion, I discuss identity conflict - what happens when immigrants and/or their children, who were born and/or raised in the New World, do not fit into mainstream society?

If you are interested in language/cultural studies, you may also want to read the following:

- English language examinations in Greece

- Primary school education in Greece

- The role of the Greek Orthodox church in the diaspora

You can find more of my writing about identity and New Zealand throughout my blog.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

Your article about Greece language is really interesting. Thanks for sharing your idea with us. I have intensive knowledge about Greece language , culture and we have organized a course about Greece language spoken and written courses and we are making a plan to teach Greece language for our students so that they will have sufficient knowledge for their native language.

ReplyDelete