"Greeks just want money, not investments," I recently wrote in my facebook page in reference to an article about protests and clashes over a goldmine."Are you for real?" a (former) reader reprimanded me. "Honestly, these generalisations are truly offensive. Next time, please speak for yourself." That's what I usually do - this is a personal blog! At any rate, Greek identity issues now make top discussion, especially in the current climate, as the preparations for the commemoration are well under way. The streets of central Athens have already been cleared of all the bitter oranges left hanging on the trees that line many of the main streets, as a way of removing the temptation of turning them into cheap ammunition.

Τomorrow is a major Greek festival and public holiday in Greece (Independence from the Turks). It coincides with the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary, which is why it receives such prominence, as it is regarded with dual significance. The day is accompanied by what looks like an outdated military street parade with government officials watching from an official marquee, while the public follows the parades, clapping and cheering as the paraders walk by them. Well, that's what used to happen. In the last two years, all military parades have been accompanied by egg/yoghurt/tomato-throwing, booing, and the paraders' turning their head away from the officials who they are supposed to be saluting, all of which recently led to the raising of the issue concerning whether the parades should be cancelled, as they no longer serve the purpose that they were originally designed for (ie to bask in our glory).

The government has decided against this, and I can't blame them. For a start, how can Greece cancel such an institution when it has been copied for many years among the Greek diaspora far away from Greece's shores? It would make Greeks in Greece look like asses. But the truth is that the Greek community in the US will be parading on New York's 5th Avenue to mark this event, in recognition of Greece's glorious moment of independence. This could not happen alongside a Greece where Greeks will be sipping their frappe, quite unruffled by anything. Were such an action to occur, this will lead to the superiority complex among the diaspora Greeks who think that they are more Greek than the Greeks who live in Greece, while the Greeks in Greece will be protesting against their inferior status in global terms and who drove them to this humiliating point. Over the years, I have gotten used to hearing how un-Greek the Greek Greeks are, but this is nothing new: it reminds me of what a Chinese friend recently told me: people of Chinese origin who have been born and raised in a Western country are often referred to as bananas (yellow on the outside, white on the inside). Given that I myself used to live among the diaspora community, what worries me about this kind of thinking is that for a while, even I believed it.

Now that I live in Greece, I realise just how sick this private joke of ours is. Such a generalisation fails to take account of how diverse Greek people are. But it does take account of an inherent trait in Greek identity: divisiveness. Once again, the tale of two cities comes into play: Greece is a country divided into two virtually equal factions. There are the tax evaders vs the payers, the public vs the private sector, the party politickers vs the independent thinkers, the urban versus the rural dwellers, the mainlanders versus the islanders, the 'Greece-for-Greeks' versus the EU-Greece sides, the traditionalists versus the modernists, the loafers versus the workers, they cheats versus the honest Greeks, and the list goes on. Given more time, it is quite easy to think of a host of other opposing facets of society that often become the topic of heated discussion, all of which show a crucial division of opinion among the Greeks. Dichotomous issues such as these, which in essence all rest on false dilemmas, plague Greece's development, and have been doing so since time immemorial.

Apart from Greek heritage, and possibly Greek citizenship and Greek language, I doubt that I can find a common denominator that truly unites Greeks. Even Greek food widely differs as little as 100 kilometres apart. I'm now living in an 'us-or-them' country. I console myself by the thought that modern Greece has always been like this, since her inception, meaning 'indecisive', 'chaotic', 'lacking unity'. To make an identity statement about Greek people is impossible. Greeks themselves cannot concur about what it is that makes them Greek.

Since the economic crisis began, the century-old writings of the satirist George Souris, a newspaper editor who lived on the island of Syros, have been given due prominence, given their pertinence in Greece's present situation:

The lyrics may sound like sweeping generalisations that are too offensive to be uttered in public. They ridicule and decry the Greeks without any positive motive. But the century (or should I say centuries) old question of the two-sided Greek identity has been the subject of many theses over the years. It was also the subject of a complete book by Nikos Dimou, a modern-day Greek satirist, under the title of "The misery of being Greek", originally published in 1975, only a year after the restoration of democracy after the junta regime, and just half a dozen years before Greece's entry to the EU. The book was actually written in 1972, but due to the heavy censorship of the press at the time, it was not published until after the dictatorship. The book was recently translated into German, providing more impetus to credit Germany for taking a hard stance on Greece.

Here are some translated excerpts from the book, reprinted from Nikos Dimou's website:

The ideas expressed in Dimou's work do not differ greatly from Souris' writing; they are related, and show a natural follow-up of the same subject. The interest that they generate today is a sign that they are viewed as timeless and highly relevant. As Dimou explains: "The fact that it [ie his book] became diachronic is evidence that the subject is discusses is deeply rooted inside us." There is still that 'us-versus-them' factor shining through all such works on the Greek identity. I myself write about 'them', while simultaneously counting myself as one of 'them' too. While this leaves little hope for a united and progressive Greece in the future, it is a sure sign that Greeks know themselves well, following Apollo's words: Γνῶθι σαυτόν (Know thyself). Such discussions are not of a racial character: they are simply a form of identity analysis, a kind of self-contemplation, if you wish. At any rate, the Misery of being Greek is a much more popular topic than the Joy of being Greek (the book with that title stopped being many printed years ago). Such works are also a sure sign of democracy: where else in the world can you blast your compatriots in this way, and still be respected by them?

The ideas expressed in Dimou's work do not differ greatly from Souris' writing; they are related, and show a natural follow-up of the same subject. The interest that they generate today is a sign that they are viewed as timeless and highly relevant. As Dimou explains: "The fact that it [ie his book] became diachronic is evidence that the subject is discusses is deeply rooted inside us." There is still that 'us-versus-them' factor shining through all such works on the Greek identity. I myself write about 'them', while simultaneously counting myself as one of 'them' too. While this leaves little hope for a united and progressive Greece in the future, it is a sure sign that Greeks know themselves well, following Apollo's words: Γνῶθι σαυτόν (Know thyself). Such discussions are not of a racial character: they are simply a form of identity analysis, a kind of self-contemplation, if you wish. At any rate, the Misery of being Greek is a much more popular topic than the Joy of being Greek (the book with that title stopped being many printed years ago). Such works are also a sure sign of democracy: where else in the world can you blast your compatriots in this way, and still be respected by them?

A word on generalisations: you shouldn't make them because you know it's wrong. By way of example, what is expressed in this post cannot apply to all Greeks, wherever they may be. We are not all one and the same. As Benjamin Broome who wrote Exploring the Greek Mosaic: A Guide to Intercultural Communication in Greece explains: "Making generalisations is not an easy task. I am sure that many Greeks will disagree about the statements I have made about their culture. The difficulty of describing cultural patterns in a manner that does not distort reality is one that challenges any writer who dares to enter a world that is not his or her own."

HA! Gotcha! I am describing my own world! Therefore, I am exempt from the rule! As the Greeks say: "όλοι εκτός παρόντες."

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

|

| 25 March, 2009, Athens |

|

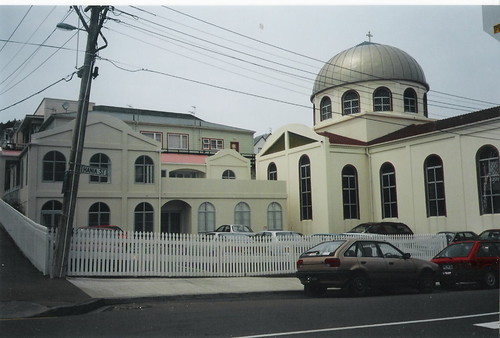

| Hania St, Wellington, New Zealand |

Now that I live in Greece, I realise just how sick this private joke of ours is. Such a generalisation fails to take account of how diverse Greek people are. But it does take account of an inherent trait in Greek identity: divisiveness. Once again, the tale of two cities comes into play: Greece is a country divided into two virtually equal factions. There are the tax evaders vs the payers, the public vs the private sector, the party politickers vs the independent thinkers, the urban versus the rural dwellers, the mainlanders versus the islanders, the 'Greece-for-Greeks' versus the EU-Greece sides, the traditionalists versus the modernists, the loafers versus the workers, they cheats versus the honest Greeks, and the list goes on. Given more time, it is quite easy to think of a host of other opposing facets of society that often become the topic of heated discussion, all of which show a crucial division of opinion among the Greeks. Dichotomous issues such as these, which in essence all rest on false dilemmas, plague Greece's development, and have been doing so since time immemorial.

Apart from Greek heritage, and possibly Greek citizenship and Greek language, I doubt that I can find a common denominator that truly unites Greeks. Even Greek food widely differs as little as 100 kilometres apart. I'm now living in an 'us-or-them' country. I console myself by the thought that modern Greece has always been like this, since her inception, meaning 'indecisive', 'chaotic', 'lacking unity'. To make an identity statement about Greek people is impossible. Greeks themselves cannot concur about what it is that makes them Greek.

Since the economic crisis began, the century-old writings of the satirist George Souris, a newspaper editor who lived on the island of Syros, have been given due prominence, given their pertinence in Greece's present situation:

"Ποιος είδε κράτος λιγοστό σ' όλη τη γη μοναδικό, Who ever saw such a small country, so unique in the whole wide world

εκατό να εξοδεύει και πενήντα να μαζεύει; that can afford to spend 100, while collecting only 50?

Να τρέφει όλους τους αργούς, να’ χει επτά πρωθυπουργούς, It nurtures all the idlers, and has seven Prime Ministers

ταμείο δίχως χρήματα και δόξης τόσα μνήματα; with a bankrupt treasury, but a country full of glorious monuments

Να' χει κλητήρες για φρουρά και να σε κλέβουν φανερά, It has bailiffs for guards, who rob you in broad daylight

κι ενώ αυτοί σε κλέβουνε τον κλέφτη να γυρεύουνε; at the same time that they rob you, they are searching for the robbers

Σπαθί αντίληψη, μυαλό ξεφτέρι, κάτι μισόμαθε κι όλα τα ξέρει Quick to respond, with a mind as sharp as a razor, he half-learnt something but he knows everything

Κι από προσπάππου κι από παππού, συγχρόνως μπούφος και αλεπού From great-grandfather to grandfather, simultaneously a buffoon and a fox

Θέλει ακόμα -κι αυτό είναι ωραίο- να παριστάνει τον Ευρωπαίο, He still wants - and this is the good part - to pretend that he is a European

στα δυο φορώντας τα πόδια που’ χει, στο' να λουστρίνι στ' άλλο τσαρούχι so he wears different two shoes: one is made of shiny patent leather, while the other is a tsarouhi

Δυστυχία σου Ελλάς, με τα τεκνά που γεννάς! O Greece, a hero's country!

'Ω Ελλάς, ηρώων χώρα, τι γαϊδάρους βγάζεις τώρα;!!" Now all you bear is donkeys!!

(The complete poem is available here).Greeks are now both blessed and cursed to be hearing this 100-year-old rhyming poem in a song that is being played regularly on Greek radio at the moment. In line with the inherent divisive indecisiveness that plagues them, Greeks can choose which version they prefer: Zouganelis' lamenting tone, hinting at the sad demise of his glorious race, or Papakonstantinou's aggressive crowd-pleasing rage in a heart-wrenching reprimanding rock rhythm. Personally, I prefer the latter.

The lyrics may sound like sweeping generalisations that are too offensive to be uttered in public. They ridicule and decry the Greeks without any positive motive. But the century (or should I say centuries) old question of the two-sided Greek identity has been the subject of many theses over the years. It was also the subject of a complete book by Nikos Dimou, a modern-day Greek satirist, under the title of "The misery of being Greek", originally published in 1975, only a year after the restoration of democracy after the junta regime, and just half a dozen years before Greece's entry to the EU. The book was actually written in 1972, but due to the heavy censorship of the press at the time, it was not published until after the dictatorship. The book was recently translated into German, providing more impetus to credit Germany for taking a hard stance on Greece.

Here are some translated excerpts from the book, reprinted from Nikos Dimou's website:

Υπάρχουν Έλληνες που προβληματίζονται με τους εαυτούς των και Έλληνες που δεν προβληματίζονται. Οι σκέψεις αυτές αφορούν περισσότερο τους δεύτερους. Είναι όμως αφιερωμένες στους πρώτους. There are Greeks who are troubled by themselves and Greeks who are not troubled. These considerations relate more to the latter. But they are dedicated to the former.Although Dimou writes about things in the way that people like to hear or read, using his wit to gain an audience, his success rests on making sweeping generalisations, while focussing on stereotypes and bordering on the highly opinionated. Who said 'all Greeks' are like this? But Dimou acknowledges that not all Greeks are the same at all. He divides them into three groups:

Ο Έλληνας ζει κυκλοθυμικά σε μόνιμη έξαρση ή ύφεση. Μία συνέπεια: απόλυτη αδυναμία αυτοκριτικής και αυτογνωσίας. The Greek lives temperamentally in a state of permanent remission or exacerbation. A consequence: the absolute impossibility of self-criticism and self-awareness.

Ο Έλληνας, όταν βλέπει τον εαυτό του στον καθρέπτη, αντικρίζει είτε τον Μεγαλέξανδρο είτε τον Κολοκοτρώνη, είτε τουλάχιστον τον Ωνάση. Ποτέ τον Καραγκιόζη. When a Greek sees himself in the mirror, he sees either Alexander the Great or Kolokotronis, or at the very least Onassis. Never Karaghiozis.

Κι όμως στην πραγματικότητα είναι ο Καραγκιόζης, που ονειρεύεται τον εαυτό του σαν Μεγαλέξανδρο. Ο Καραγκιόζης με τα πολλά επαγγέλματα, τα πολλά πρόσωπα, την μόνιμη πείνα και την μία τέχνη: της ηθοποιίας. Yet the reality is Karagiozis, who dreams of himself as Alexander the Great; Karagiozis with his many professions, multiple identities, permanent hunger and an art: acting.

Πόσοι είναι οι Έλληνες, εκτός από τον Εμμανουήλ Ροΐδη, που έχουν δει το πρόσωπό τους στον καθρέφτη; How many Greeks, apart from Emmanuel Roidis, have seen their faces in the mirror?

Βασικά ο Έλληνας αγνοεί την πραγματικότητα. Ζει δύο φορές πάνω από τα οικονομικά του μέσα. Υπόσχεται τα τριπλά από αυτά που μπορεί να κάνει. Γνωρίζει τα τετραπλάσια από αυτά που πραγματικά έμαθε. Αισθάνεται (και συναισθάνεται) τα πενταπλάσια από όσα πραγματικά νοιώθει. The Greek basically ignores reality. He lives two times above his financial capabilities. He promises himself triple of what he can actually do. He knows four times what he has actually learned. He feels (and is aware of) five times what he can actually feel.

Η υπερβολή δεν είναι μόνο εθνικό ελάττωμα. Είναι τρόπος ζωής των Ελλήνων. Είναι η συνισταμένη του εθνικού τους χαρακτήρα. Είναι η βασική αιτία της δυστυχίας τους αλλά και η μεγάλη τους δόξα. Γιατί στο αυτο-συναίσθημα, η υπερβολή λέγεται λεβεντιά. Excess is not just a national defect. It is a way of life for the Greeks. It is the result of their national character. It is the main cause of their misery as well as their vast glory. For in the self-conscious, excess is called bravery.

Η ευτυχία της δυστυχίας του Νεοέλληνα εκφράζεται τέλεια στην ελληνική γκρίνια. The joy of the misery of the modern Greek is expressed perfectly in the Greek nagging syndrome.

Ο ελληνικός νόμος του Parkinson: Δύο Έλληνες κάνουν σε δύο ώρες (λόγω διαφωνίας) ό,τι ένας Έλληνας κάνει σε μία ώρα. Parkinson's law in Greek: Two Greeks do in two hours (due to conflicts of opinion) what one Greek does in one hour.

Η σχέση μας με τους αρχαίους είναι μία πηγή του εθνικού πλέγματος κατωτερότητας. Η άλλη είναι η σύγκριση στο χώρο και όχι στο χρόνο. Με τους σύγχρονους «ανεπτυγμένους». Με την «Ευρώπη». Our relationship with our ancient race is a source of the national web of inferiority, as is the comparison of place and not of time. With the modern "developed" people. With "Europe."

Όταν ένας Έλληνας μιλάει για την Ευρώπη, αποκλείει αυτόματα την Ελλάδα. Όταν ένας ξένος μιλάει για την Ευρώπη, δεν διανοούμαστε ότι μπορεί να μη περιλαμβάνει και την Ελλάδα. When a Greek talks of Europe, he automatically excludes Greece. When a foreigner talks about Europe, we cannot put it into our head that he does not include Greece in it.

Γεγονός είναι πως - ό,τι και αν λέμε - δεν νιώθουμε Ευρωπαίοι. Νιώθουμε απ' έξω. Και το χειρότερο είναι, που τόσο μας νοιάζει και μας καίει, όταν μας το λένε... It is a fact that, whatever we may believe, we do not feel European. We feel like outsiders. And the worst part is that it grieves us to no end when we are told this...

Στο θέμα της κληρονομιάς τους, θα χώριζα τους Έλληνες σε τρεις κατηγορίες - τους συνειδητούς, τους ημι-συνειδητούς και τους μη-συνειδητούς. On the issue of their heritage, I would divide the Greeks into three categories - the conscious, the semi-conscious and the non-conscious.

Οι πρώτοι (λίγοι) ξέρουν. Έχουν νοιώσει το τρομερό βάρος της κληρονομιάς. Έχουν καταλάβει το απάνθρωπο επίπεδο τελειότητας του λόγου ή της μορφής των παλιότερων. Και τούτο τους συντρίβει. The first (few) "know". They feel the terrible burden of their inheritance. They have understood the inhuman level of perfection in the speech or form of their predecessors. And it crushes them.

Οι δεύτεροι (και οι περισσότεροι) δεν ξέρουν άμεσα. Έχουν όμως «ακουστά». Είναι σαν τους γιους του διάσημου φιλόσοφου, που δεν μπορούν να καταλάβουν τα έργα του, βλέπουν όμως πως όσοι ξέρουν, τα τιμούν και τα βραβεύουν. Τους ενοχλεί αλλά και τους κολακεύει η φήμη. Επαίρονται πάντα όταν μιλούν σε τρίτους. The second (and largest group) does not know directly. But they have "heard" about it. It's something like the sons of the famous philosopher, who cannot understand his works, but they realise that those who do understand them honor and reward them. They are at the same time annoyed and flattered by this reputation. They always boast about it when speaking to others.

Η τρίτη κατηγορία-οι μη συνειδητοί- είναι οι παρθένοι και αγνοί (γράφε ασπούδαχτοι: Μακρυγιάννης, Θεόφιλος). Έχουν ακούσει για τους παλιούς σε μύθους και θρύλους, που τους έχουν αφομοιώσει σαν λαϊκά παραμύθια. Αυτοί οι αγνοί δημιούργησαν την λαϊκή παράδοση και τέχνη. The third category - the non-conscious - are like chaste virgins (read 'self-learned': Makriyannis, Theophilus). They have heard about the ancient people in myths and legends, which they have assimilated as folk tales. These pure people created our popular traditions and art.

Ωστόσο η συντριπτική πλειοψηφία των ημιμαθών με το μόνιμο κρυφό πλέγμα κατωτερότητας απέναντι στους αρχαίους, καθορίζει τη στάση και το ύφος του συνόλου. However the vast majority of the semi-educated live in a permanent web of an inferiority complex towards the ancient people, which designates the stance and style of the general whole.

(More excerpts can be found on Nikos Dimou's website.)

The ideas expressed in Dimou's work do not differ greatly from Souris' writing; they are related, and show a natural follow-up of the same subject. The interest that they generate today is a sign that they are viewed as timeless and highly relevant. As Dimou explains: "The fact that it [ie his book] became diachronic is evidence that the subject is discusses is deeply rooted inside us." There is still that 'us-versus-them' factor shining through all such works on the Greek identity. I myself write about 'them', while simultaneously counting myself as one of 'them' too. While this leaves little hope for a united and progressive Greece in the future, it is a sure sign that Greeks know themselves well, following Apollo's words: Γνῶθι σαυτόν (Know thyself). Such discussions are not of a racial character: they are simply a form of identity analysis, a kind of self-contemplation, if you wish. At any rate, the Misery of being Greek is a much more popular topic than the Joy of being Greek (the book with that title stopped being many printed years ago). Such works are also a sure sign of democracy: where else in the world can you blast your compatriots in this way, and still be respected by them?

The ideas expressed in Dimou's work do not differ greatly from Souris' writing; they are related, and show a natural follow-up of the same subject. The interest that they generate today is a sign that they are viewed as timeless and highly relevant. As Dimou explains: "The fact that it [ie his book] became diachronic is evidence that the subject is discusses is deeply rooted inside us." There is still that 'us-versus-them' factor shining through all such works on the Greek identity. I myself write about 'them', while simultaneously counting myself as one of 'them' too. While this leaves little hope for a united and progressive Greece in the future, it is a sure sign that Greeks know themselves well, following Apollo's words: Γνῶθι σαυτόν (Know thyself). Such discussions are not of a racial character: they are simply a form of identity analysis, a kind of self-contemplation, if you wish. At any rate, the Misery of being Greek is a much more popular topic than the Joy of being Greek (the book with that title stopped being many printed years ago). Such works are also a sure sign of democracy: where else in the world can you blast your compatriots in this way, and still be respected by them?

*** *** ***

HA! Gotcha! I am describing my own world! Therefore, I am exempt from the rule! As the Greeks say: "όλοι εκτός παρόντες."

UPDATE: After making personal contact with the author, I learnt that an English translation of Nikos Dimou's book will soon be available, published through John Hunt by Zero Books. I will give him the last word: Dimou believes that in order to survive in this modern world, Greeks need to reinvent themselves. As if they haven't got enough difficulties...

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

No comments:

Post a Comment