Titika rises and goes into her kitchen. It is still dark, but she cannot sleep any longer. She never sleeps past this hour. She is used to getting up at so early. She moves towards the kitchen, the warmest part of the house, where the wood-fire may still be burning, if she is lucky, and indeed, today she is. The embers are visible through the glass pane on the oven door. There is still a little life left in them.

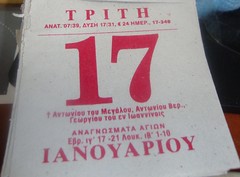

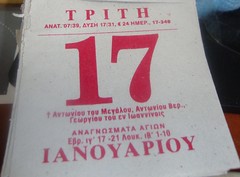

She makes her way to the calendar on the wall, a present from her grandson. When he stays with her at the weekends, he likes to peel the pages off for her. She lets him read the day's story on the back of each page. But today is a weekday, and he's at school in the town where he lives. She carefully lifts yesterday's page to reveal the new date, laying the old page on the table.

She must be ready at the first light. What time does the sun rise today? she wonders. Although she is used to moving around in the dark conditions of the three rooms of her village home, she turns on the electric light to read the sunrise time written on the calendar: 7.39. Dawn will be coming in an hour, she thinks, as she goes back to the switch and turns off the light. The sheep need to be milked before being taken out to graze.

She must be ready at the first light. What time does the sun rise today? she wonders. Although she is used to moving around in the dark conditions of the three rooms of her village home, she turns on the electric light to read the sunrise time written on the calendar: 7.39. Dawn will be coming in an hour, she thinks, as she goes back to the switch and turns off the light. The sheep need to be milked before being taken out to graze.

The pot of μαλοτίρα had been left on the wood-fired stove from the previous evening, so that it will be warm to drink as soon as she wakes up. As she pours out the tea through a strainer, she cups her hands around the glass, warming them up in the icy chill of the early morning. Her throat welcomes the warm liquid, comforting her as it flows through her body.

She stokes the previous night's fire to keep it going and pushes the early morning ashes close to the centre so that they will pass through the grate and not choke the flames. Then she adds another log and watches it through the glass as the brittle splinters flicker alight and the log slowly catches fire, starting from the middle outwards.

According to the calendar, the moon is still in the last quarter, so there is plenty of time left to till the land lying fallow, now that it would be at its most frothy. As she drinks her tea, she hopes it will not start to rain, as this would mar her plans after milking the sheep. There is still a lot of tilling to do to get the land ready for the next sowing cycle.

Although she knows it is Tuesday, she checks the calendar once again to verify this. The letters are large and she does not need the light on to see them. The country GP will be coming today. He comes to the village every Tuesday. She needs to get a prescription filled for her osteoporosis tablets, so she will have to spend an hour or two at the former school building to get this done. Doctors are busy people - they can never be prompt. But this queuing gives her a chance to while her time away with the other villagers, the few that are left; despite the problems that the world finds itself in today, not many people care to return to this one. Tuesday is a time when her sparsely scattered neighbours come together to find out what everyone else is up to. They will talk about their children and grandchildren, the weather, the olive harvest, the price of olive oil and the general state of the economy. Everyone will add their bit to the conversation, and even after each person leaves the queue and takes their turn with the country GP, they will still linger until everyone has finished their work here, just to make sure that they have all seen each other and missed no one. Even the kafeneio will be open today. Although Titika will not order anything there, she will take a seat with the other village women just to catch up with each other's lives.

She looks up at the calendar. TUESDAY... 17... January... She mulls over the 17. It reminds her of something. She looks below the number: "Antonia". Antonia? Yes! It's her sister's nameday! She thinks quickly: It's morning here... so it's evening there. This is her way of remembering time differences between continents. She knows that this formula works for morning and evening, but she isn't sure about the middle of the day (the middle of the night is insignificant as she herself is bound to be sleeping). But it's still dark here too, which makes her hesitate. Talking on the telephone so early in the morning still feels unnatural to her, even though she knows her sister will not be sleeping at that hour. She may even be waiting for her call. At this moment, she also reminds herself that it's not a day of fast, so she can cook what she likes. As it's her sister's nameday, she knows this information off by heart and does not need to check it on the calendar page.

She dunks a piece of stale bread into the tea and lets it soak just enough to soften it. She then drains it over the cup before lowering her head to take a bite, taking care not to move the rusk away from the teacup; it was still dripping randomly. She watches the flames leaping and listens to the wood crackling away, as she looks at the empty pot next to the oven.

Dawn is breaking. A beam of light streams in through the window at the point where the curtains are drawn but do not meet. Every time she looks at that gap, she remembers the day she stitched them. When she hung them up, she could see at once that they needed to be amended slightly - she had sewn the hem about half a centimetre too inwards on one of them. But she never did take them down. The curtains have been there for a long time, and they will not be coming down soon. The colour of the room now lightens, as it fills with the first light of the new day.

What shall I fill that pot with today? she wonders. Even though she is a widow and lives alone, she never fails to eat a cooked meal every day. She remembers the leftover braised cauliflower in the fridge which she left for the chickens. They need to be fed too, but she will do that after lunch. The days are still too short, so that all the chores are crammed in tightly. She begins to organise her day's work in her head.

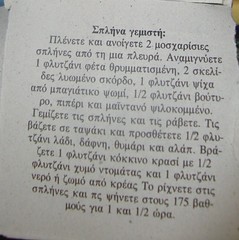

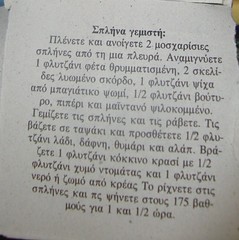

By now, there is enough light to read yesterday's calendar page. This year, instead of the calendar she was used to getting with a μαντινάδα written on the back of each page, her daughter-in-law had bought her a calendar with a recipe for each day. She thought it was quite a novel idea. At any rate, she had tired of the μαντινάδες. Ever since her husband had died, she found it difficult to laugh by herself, all alone in her house, even though she might have found something that she was reading or watching on TV to be very funny.

She picks up yesterday's page and turns it over: Σπλήνα γεμιστή. Filled spleen! Where would she find an animal's spleen at this time of the year, she wondered, smiling. At that moment, she did actually want to laugh, but the image of her husband came into her mind, and sadness overcame her. Were he still alive, if she expressed an interest in cooking spleen that day, he would have gone to all lengths to find it for her.

She picks up yesterday's page and turns it over: Σπλήνα γεμιστή. Filled spleen! Where would she find an animal's spleen at this time of the year, she wondered, smiling. At that moment, she did actually want to laugh, but the image of her husband came into her mind, and sadness overcame her. Were he still alive, if she expressed an interest in cooking spleen that day, he would have gone to all lengths to find it for her.

She has finished drinking her tea, and now there is enough light in the house for her to move about her kitchen with ease. It's now or never, she thinks. Titika makes her way to the phone. The address book sits under it on a small round table in the corner of the hallway. She flicks through it to find her sister's phone number. It's complicated to remember it, so many zeros at the beginning, so many numbers to dial. It looks strange, in the same way that the name of the country her sister lives in sounds strange: Ne-a Zi-la-thia.

She dials the numbers slowly, pressing each one deliberately and listening to the beep that each one makes as she dials it. She waits to hear the ring tone, which sounds different from the one she is used to hearing at her end.

"Bring-bring... bring-bring... bring-bring..." It's ringing. "Bring-bring... bring-bring... bring-bring..." But no one is answering. She lets the phone ring a little while longer, and imagines what her sister's family may be doing now. Perhaps they are out. It's summer, and they may be returning from the beach. Antonia has told her that they live near the sea. The weather will be sunny and pleasant. Perhaps they may have decided to stay out at a nice taverna for an outdoor meal. Maybe--

"Hello?" Someone is home.

"Ποιός είναι;" She feels it is only right to ask who it is that answered the phone (and in the only language she knows), as she only speaks to her sister. Only her sister will understand her, as no one else speaks Greek in her sister's house.

"Ma," she hears a girl's voice saying, along with some other words she does not understand. The scuffling sound is heard of the phone changing hands.

"Τιτίκα!" Her sister's voice booms over the line. She was expecting her to call.

"Αντωνία μου!" Titkika sheds a tear as she utters her sister's name, trying to keep her voice smooth. This happens every time she phones her for her nameday; she phones her only on this day. "Χρόνια πολλά, αδελφούλα μου!" Now Titika is crying. She has not seen Antonia for thirty years, and Titika has never made a return trip to the village since she left. The sisters have a twenty-year age difference, but this has not waned Antonia's affection for her youngest sibling. She was more like her daughter than her sister as their mother had died in childbirth, and Titika raised Antonia amidst her own two children who were older than her own sister. She can never forget the day Antonia left the family home after falling in love with a tourist. She wrote letters for the first five or six years, but the letters lessened over time. Now Titika looked forward to receiving a Christmas card at the end of each year. When she received it, she felt relieved, as it allowed her to believe that all was well with Antonia, her baby.

The sisters made some small talk for a few minutes, asking each other questions about everyday life in their respective homes: what time is it there, how old's your grandson/daughter now, how are my brothers/your husband?

"What's the weather like there now, Antonia? It's very very cold here," Titika said.

"Oh, it's cold here too!" Antonia replied.

"But it's summer over there!"

"Oh, Titika, it's never that hot here. Now it's very windy and the sun is hidden in the clouds."

"Oh." Titika found all conversations concerning the weather in Nea Zilathia very confusing.

"Well, I don't want the clock to run up too many units, so I won't keep you any longer." Five minutes. It seemed to pass very quickly. But it was only five minutes. Titika could see the kitchen clock from where the phone was. Antonia always had her mind on the time.

"Νά 'σαι καλά αδελφούλα μου!" Titika spoke exuberantly. She was happy to hear her sister's voice once again, and for a moment, she forgot her sadness about knowing that she would not hear it for another year. She sounds happy, Titika thought. It never crossed her mind that Antonia could be unhappy. She had a husband, a daughter and a home. The ξενιτειά has done her good. Although she felt it was a cruel blow to her when Antonia left the family home, she knew it had to happen for Antonia's good, and she was happy for that. It saddened her that she could not communicate with Titika's daughter or husband; it never occurred to her that they did not want to communicate with her. Antonia was well. And now, Titika will have something to tell the other villagers at the school as she waits for her turn to see the country doctor.

Satisfied with herself that she had completed her first task of the day, she began to bundle herself up for the cold outdoors, as the first rays of the sun began to appear. In the short days of winter, the day would pass quickly. Before night falls, she will be sitting on the sofa by the wood fire again, watching television until she nods off to sleep. What a pity the calendar contained only bible readings and not the TV guide!

You need:

2 beef spleens, opened from one side (if Titika had cauliflower growing in her garden, no doubt she would have had some cabbage too, so I used cabbage leaves)

For the filling, you need:

1 cup of feta, crumbled (if Titika is Cretan, no doubt she would use her own production of mizithra)

2 cloves of garlic

1 cup of soft breadcrumbs from stale bread

1/2 cup of butter (if Titika is Cretan, she'd use olive oil)

some finely chopped parsley

pepper

For the sauce, you need:

1/2 cup olive oil

1 glass of red wine

1/2 cup of tomato juice (I used fresh pureed tomato)

1 cup of stock or water ( I used the latter)

a bay leaf

some thyme

salt

Clean and open the spleens from one side (if using cabbage leaves, boil a few large ones till soft and pliable). Mix together the ingredients for the filling. Fill the spleens (or cabbage leaves) and sew them up (if using cabbage leaves, just make them into a parcel). Place them on a baking dish, and pour over the oil and seasonings.

Heat up the wine with the tomato juice and water or stock. Pour over the parcels and cook for one and a half hours at 175C (or less if using cabbage leaves - the stuffing doesn't need a long time to cook).

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

She makes her way to the calendar on the wall, a present from her grandson. When he stays with her at the weekends, he likes to peel the pages off for her. She lets him read the day's story on the back of each page. But today is a weekday, and he's at school in the town where he lives. She carefully lifts yesterday's page to reveal the new date, laying the old page on the table.

She must be ready at the first light. What time does the sun rise today? she wonders. Although she is used to moving around in the dark conditions of the three rooms of her village home, she turns on the electric light to read the sunrise time written on the calendar: 7.39. Dawn will be coming in an hour, she thinks, as she goes back to the switch and turns off the light. The sheep need to be milked before being taken out to graze.

She must be ready at the first light. What time does the sun rise today? she wonders. Although she is used to moving around in the dark conditions of the three rooms of her village home, she turns on the electric light to read the sunrise time written on the calendar: 7.39. Dawn will be coming in an hour, she thinks, as she goes back to the switch and turns off the light. The sheep need to be milked before being taken out to graze. The pot of μαλοτίρα had been left on the wood-fired stove from the previous evening, so that it will be warm to drink as soon as she wakes up. As she pours out the tea through a strainer, she cups her hands around the glass, warming them up in the icy chill of the early morning. Her throat welcomes the warm liquid, comforting her as it flows through her body.

She stokes the previous night's fire to keep it going and pushes the early morning ashes close to the centre so that they will pass through the grate and not choke the flames. Then she adds another log and watches it through the glass as the brittle splinters flicker alight and the log slowly catches fire, starting from the middle outwards.

According to the calendar, the moon is still in the last quarter, so there is plenty of time left to till the land lying fallow, now that it would be at its most frothy. As she drinks her tea, she hopes it will not start to rain, as this would mar her plans after milking the sheep. There is still a lot of tilling to do to get the land ready for the next sowing cycle.

Although she knows it is Tuesday, she checks the calendar once again to verify this. The letters are large and she does not need the light on to see them. The country GP will be coming today. He comes to the village every Tuesday. She needs to get a prescription filled for her osteoporosis tablets, so she will have to spend an hour or two at the former school building to get this done. Doctors are busy people - they can never be prompt. But this queuing gives her a chance to while her time away with the other villagers, the few that are left; despite the problems that the world finds itself in today, not many people care to return to this one. Tuesday is a time when her sparsely scattered neighbours come together to find out what everyone else is up to. They will talk about their children and grandchildren, the weather, the olive harvest, the price of olive oil and the general state of the economy. Everyone will add their bit to the conversation, and even after each person leaves the queue and takes their turn with the country GP, they will still linger until everyone has finished their work here, just to make sure that they have all seen each other and missed no one. Even the kafeneio will be open today. Although Titika will not order anything there, she will take a seat with the other village women just to catch up with each other's lives.

She looks up at the calendar. TUESDAY... 17... January... She mulls over the 17. It reminds her of something. She looks below the number: "Antonia". Antonia? Yes! It's her sister's nameday! She thinks quickly: It's morning here... so it's evening there. This is her way of remembering time differences between continents. She knows that this formula works for morning and evening, but she isn't sure about the middle of the day (the middle of the night is insignificant as she herself is bound to be sleeping). But it's still dark here too, which makes her hesitate. Talking on the telephone so early in the morning still feels unnatural to her, even though she knows her sister will not be sleeping at that hour. She may even be waiting for her call. At this moment, she also reminds herself that it's not a day of fast, so she can cook what she likes. As it's her sister's nameday, she knows this information off by heart and does not need to check it on the calendar page.

She dunks a piece of stale bread into the tea and lets it soak just enough to soften it. She then drains it over the cup before lowering her head to take a bite, taking care not to move the rusk away from the teacup; it was still dripping randomly. She watches the flames leaping and listens to the wood crackling away, as she looks at the empty pot next to the oven.

Dawn is breaking. A beam of light streams in through the window at the point where the curtains are drawn but do not meet. Every time she looks at that gap, she remembers the day she stitched them. When she hung them up, she could see at once that they needed to be amended slightly - she had sewn the hem about half a centimetre too inwards on one of them. But she never did take them down. The curtains have been there for a long time, and they will not be coming down soon. The colour of the room now lightens, as it fills with the first light of the new day.

What shall I fill that pot with today? she wonders. Even though she is a widow and lives alone, she never fails to eat a cooked meal every day. She remembers the leftover braised cauliflower in the fridge which she left for the chickens. They need to be fed too, but she will do that after lunch. The days are still too short, so that all the chores are crammed in tightly. She begins to organise her day's work in her head.

By now, there is enough light to read yesterday's calendar page. This year, instead of the calendar she was used to getting with a μαντινάδα written on the back of each page, her daughter-in-law had bought her a calendar with a recipe for each day. She thought it was quite a novel idea. At any rate, she had tired of the μαντινάδες. Ever since her husband had died, she found it difficult to laugh by herself, all alone in her house, even though she might have found something that she was reading or watching on TV to be very funny.

She picks up yesterday's page and turns it over: Σπλήνα γεμιστή. Filled spleen! Where would she find an animal's spleen at this time of the year, she wondered, smiling. At that moment, she did actually want to laugh, but the image of her husband came into her mind, and sadness overcame her. Were he still alive, if she expressed an interest in cooking spleen that day, he would have gone to all lengths to find it for her.

She picks up yesterday's page and turns it over: Σπλήνα γεμιστή. Filled spleen! Where would she find an animal's spleen at this time of the year, she wondered, smiling. At that moment, she did actually want to laugh, but the image of her husband came into her mind, and sadness overcame her. Were he still alive, if she expressed an interest in cooking spleen that day, he would have gone to all lengths to find it for her. She has finished drinking her tea, and now there is enough light in the house for her to move about her kitchen with ease. It's now or never, she thinks. Titika makes her way to the phone. The address book sits under it on a small round table in the corner of the hallway. She flicks through it to find her sister's phone number. It's complicated to remember it, so many zeros at the beginning, so many numbers to dial. It looks strange, in the same way that the name of the country her sister lives in sounds strange: Ne-a Zi-la-thia.

She dials the numbers slowly, pressing each one deliberately and listening to the beep that each one makes as she dials it. She waits to hear the ring tone, which sounds different from the one she is used to hearing at her end.

"Bring-bring... bring-bring... bring-bring..." It's ringing. "Bring-bring... bring-bring... bring-bring..." But no one is answering. She lets the phone ring a little while longer, and imagines what her sister's family may be doing now. Perhaps they are out. It's summer, and they may be returning from the beach. Antonia has told her that they live near the sea. The weather will be sunny and pleasant. Perhaps they may have decided to stay out at a nice taverna for an outdoor meal. Maybe--

"Hello?" Someone is home.

"Ποιός είναι;" She feels it is only right to ask who it is that answered the phone (and in the only language she knows), as she only speaks to her sister. Only her sister will understand her, as no one else speaks Greek in her sister's house.

"Ma," she hears a girl's voice saying, along with some other words she does not understand. The scuffling sound is heard of the phone changing hands.

"Τιτίκα!" Her sister's voice booms over the line. She was expecting her to call.

"Αντωνία μου!" Titkika sheds a tear as she utters her sister's name, trying to keep her voice smooth. This happens every time she phones her for her nameday; she phones her only on this day. "Χρόνια πολλά, αδελφούλα μου!" Now Titika is crying. She has not seen Antonia for thirty years, and Titika has never made a return trip to the village since she left. The sisters have a twenty-year age difference, but this has not waned Antonia's affection for her youngest sibling. She was more like her daughter than her sister as their mother had died in childbirth, and Titika raised Antonia amidst her own two children who were older than her own sister. She can never forget the day Antonia left the family home after falling in love with a tourist. She wrote letters for the first five or six years, but the letters lessened over time. Now Titika looked forward to receiving a Christmas card at the end of each year. When she received it, she felt relieved, as it allowed her to believe that all was well with Antonia, her baby.

The sisters made some small talk for a few minutes, asking each other questions about everyday life in their respective homes: what time is it there, how old's your grandson/daughter now, how are my brothers/your husband?

"What's the weather like there now, Antonia? It's very very cold here," Titika said.

"Oh, it's cold here too!" Antonia replied.

"But it's summer over there!"

"Oh, Titika, it's never that hot here. Now it's very windy and the sun is hidden in the clouds."

"Oh." Titika found all conversations concerning the weather in Nea Zilathia very confusing.

"Well, I don't want the clock to run up too many units, so I won't keep you any longer." Five minutes. It seemed to pass very quickly. But it was only five minutes. Titika could see the kitchen clock from where the phone was. Antonia always had her mind on the time.

"Νά 'σαι καλά αδελφούλα μου!" Titika spoke exuberantly. She was happy to hear her sister's voice once again, and for a moment, she forgot her sadness about knowing that she would not hear it for another year. She sounds happy, Titika thought. It never crossed her mind that Antonia could be unhappy. She had a husband, a daughter and a home. The ξενιτειά has done her good. Although she felt it was a cruel blow to her when Antonia left the family home, she knew it had to happen for Antonia's good, and she was happy for that. It saddened her that she could not communicate with Titika's daughter or husband; it never occurred to her that they did not want to communicate with her. Antonia was well. And now, Titika will have something to tell the other villagers at the school as she waits for her turn to see the country doctor.

Satisfied with herself that she had completed her first task of the day, she began to bundle herself up for the cold outdoors, as the first rays of the sun began to appear. In the short days of winter, the day would pass quickly. Before night falls, she will be sitting on the sofa by the wood fire again, watching television until she nods off to sleep. What a pity the calendar contained only bible readings and not the TV guide!

*** *** ***

Of course, Titika did not have a spleen on standby to cook with that day, as the recipe stated on the back of the page for Monday 16 January, but even people living in villages desire to eat something different from the routine Greek meals. I imagine that her spirits may have lifted after speaking with her sister that day, and she might have used this recipe as a base for something more creative in her kitchen. I've translated the recipe as I read it on the page, but my photos show how I changed it to suit the ingredients I had at home.You need:

2 beef spleens, opened from one side (if Titika had cauliflower growing in her garden, no doubt she would have had some cabbage too, so I used cabbage leaves)

Titika's meal is a frugal cheap and Greek one. To some people, it may look poor because it uses very cheap ingredients. But I doubt that many people living in an urban area can enjoy a recipe like this one, because the ingredients and the cooking method that they will use will not be as fresh or natural as Titika's. It's hard for me to describe in words how tastythis meal was. But it smelt heavenly, and it tasted delicious. I would liken it to meat stuffing of the highest quality.

1 cup of feta, crumbled (if Titika is Cretan, no doubt she would use her own production of mizithra)

2 cloves of garlic

1 cup of soft breadcrumbs from stale bread

1/2 cup of butter (if Titika is Cretan, she'd use olive oil)

some finely chopped parsley

pepper

For the sauce, you need:

1/2 cup olive oil

1 glass of red wine

1/2 cup of tomato juice (I used fresh pureed tomato)

1 cup of stock or water ( I used the latter)

a bay leaf

some thyme

salt

Clean and open the spleens from one side (if using cabbage leaves, boil a few large ones till soft and pliable). Mix together the ingredients for the filling. Fill the spleens (or cabbage leaves) and sew them up (if using cabbage leaves, just make them into a parcel). Place them on a baking dish, and pour over the oil and seasonings.

Heat up the wine with the tomato juice and water or stock. Pour over the parcels and cook for one and a half hours at 175C (or less if using cabbage leaves - the stuffing doesn't need a long time to cook).

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

well, you made this expat cry, sitting alone in her kitchen, thousands of miles from beloved siblings ...plus thinking of her yiayia who came to the states and then rarely saw her sisters afterwards. the phone calls came, just as you described. the calendars were in each house, just as you say. every sentence you wrote fit the bill. wonderful.

ReplyDeleteMy own family lives 3,000 km away but we have MSN on Facebook where I talk to my mom and dad each morning who are in their 80's. Once in a while my sister will be on Skype.

ReplyDeleteWHAT a lovely story! I think I will be just like her some day. Once again, Maria, I have to say that you write so beautifully. This story made me think of my Norwegian grandmother. I am rather sad these days thinking of all the family members who have passed away. Now I am one of the oldest ones remaining and I am not even that OLD!

ReplyDeleteCame across this page when searching for what day of the week it was - random. Found myself a nice recipe though! :-) So What Day Is It Today? answered my query for anyone else that is looking. Embarassing but I find it all to easy to lose track of the day of the week in this day and age!!

ReplyDelete