|

| 26/1/2012 |

|

| 27/1/2012 |

|

| 28/1/2012 |

Sokrati felt the quake, like he feels all minor shakes and tremors, even ones that none of his family members ever feel. Sokrati had bad memories of earthquakes. He came from the generation of those who had lived in the

great quake of Thessaloniki in June of 1978. What seemed like a series of minor tremors in the previous two years was actually a build-up to the final crescendo that was played out in the early summer.

It had started in the

previous winter before the big one. Although he didn't actually feel it himself, he was woken up by his

parents the night the first shake happened, who then helped him to dress and take him outdoors to an open space close to their apartment building. The northern Greek air was seasonably freezing. Those who had cars - his family did not - huddled up inside them, while the others were stranded in the cold night air.

After that initial quake, there were more. At the time, he did not understand the full meaning of his parents' actions: why they left the apartment (or the school room, or the office, wherever they found themselves) in a rush. By spring he had gotten bored of going out onto the road. By the beginning of June, as he felt the

earthquakes, he was able to estimate how big they were. Most people had become quite good at this skill, and most of the time, they were getting the quoted Richter scale figure right. The tremors were getting noticeably stronger, going from 4 in the winter to 5 in spring. But people were taking fewer precautions because the tremors were just that: a minor jolt with no damage. Everyone just carried on with what they were doing and forgot about them.

Then one night, while he was with his family at the house of a relative, the big one started. he could tell something wasn't right when he saw the cupboards flying open and everything falling out, smashing onto the floor. It seemed to last for a long long time. Everyone huddled under the door

casings and waited until it had finished and rushed out in great panic. On that night, literally everyone came out of their homes. They all headed to an open area near a forest clearing where there was a dry stream bed, which would have been a racing river had it been winter.

Later, they heard that it measured 6.2 on the Richter scale and they all heard about the block of flats that had collapsed in the

center of the city. Sokrati never went back home that summer. Instead, he was first sent to live with an aunt in a small village outside the centre of Thessaloniki, where everyone slept outdoors in the fields or in their cars every night for a week. As a child, he thought he was living the sweet life, leaving the crowded city and sleeping outdoors from the beginning of summer, something like camping among the company of good friends. Then he was sent to his grandparents village near Ioannina. They were sleeping in a tent on the dry stream bed along with

hundreds of other people for the rest of the summer. he only returned to Thessaloniki in September after all the apartment blocks were inspected and found to be quite safe.

Sokrati's second experience with a serious earthquake, if vicarious in nature, was that of

Athens in 1999. The apartment he had rented only two months before the quake with his wife was deemed unfit for human inhabitation by the authorities. They discovered this when they returned from their annual holidays in Crete. When the tremor actually occurred, they were sunning themselves on the Cretan seashore. Sokrati and Rania were both thankful that they were not at home when the earthquake struck; they would undoubtedly have been in their state-job offices which were housed in crumbling buildings that had received little maintenance over the years. Sokrati's office was significantly affected in the quake, while Rania was luckier than him. His building had serious structural damage; for the next two years, he worked from a prefab. When he was studying in England, he found it strange to see people in the Science Museum in London paying to get into an earthquake simulator to

get the feeling of a seismic tremor. He knew that feeling very well and felt no urge to revive it.

Sokrati and Rania were both woken up by the latest quake, but Rania did not feel particularly moved to get out of bed. She waited to hear whether the children had felt it. On detecting no sound or movement from their room, she turned over in the bed to catch up on her beauty sleep. But Sokrati had already jumped up.

"C'mon, get a move on!" he hissed loudly. Coupled with his occupational field (geology), Sokrati was taking no chances. He had been shaken enough times to develop his own well-thought out earthquake routine, however misguided it might have sounded to someone else.

Rania knew what was coming up. She could not change Sokrati's way of thinking now, not least at half-past three in the morning. Although this was not the first time that they had experienced an earthquake in Hania, she knew that Sokrati was waiting for the big one to come - everything happens in threes, he keeps telling her. His belief in folklore was not reduced after attaining his PhD; in fact, it became more highly attuned, as that was about the time they had moved to Crete in order to be nearer to Rania's parents so that they could raise a family with fewer worries about baby-sitters and home-cooked meals. Coming to the small town that his wife had been raised in and living close to people who had never left it immensely assisted in his reverting to former habits. She got up and dressed herself at a comfortable pace, much to Sokrati's annoyance as he watched her; he would have to wake the children, a thought that he did not treasure, as it would mean having to hear his daughter curse him in her sleep, while his son who usually slept like a log would be difficult to get upright, let alone dressed.

When they were all up and had put on their winter jackets, they left the apartment without making too much noise. No one else seemed to have gotten up. They all boarded the car. There were no lights in any of the other apartments, save one: the doctor's apartment had its lights on. Perhaps he had also felt the earthquake, but did not feel the need to vacate his apartment. The children had taken a pillow and blanket with them - they were well drilled in their father's earthquake routine. They already knew that if one hour did not pass, their father would not allow them to enter the house. The great seismologist that he believed himself to be feared a stronger tremor that would follow within the next sixty minutes. It was zero degrees Celsius and they were all freezing.

During that hour, the children slowly drifted off to sleep. Rania tried not to express her sarcasm towards her husband's panic. This was simply the result of his methodical one-track-mind approach to handling the crisis that he was facing right at this minute. It reminded her of a flow-chart, which he was used to seeing a lot of in his work. But he was also used to taking the same route, instead of seeking alternatives, and since earthquakes were totally unpredictable, neither of them had had much experience in pre-planning them. All decisions were taken on the spot, using the same old approach. Although she would have preferred to curl up and sleep like the children were doing, she found it difficult to do this. The front seat of the car did not lend itself to such luxuries. Besides, she had Sokrati's sanity to think of. His fear of the big one striking any moment now would not allow him to sleep at all. It was no use trying to tell him that earthquakes could not be predicted. He believed he'd worked that one out too.

So they stayed in the

car which was parked opposite the apartment block, on an empty section of land. The road was lined with apartment blocks, except for this empty space. It was only by chance that this section of land was not covered by another apartment block just like the one they lived in. The landlord of half the street had built three apartment blocks, one for each of his children to inherit. He would have started on a fourth one, had one of his sons not died in a car accident, which meant that there was no need to build a fourth apartment block - the third one he had built was already superfluous. Overcome by grief, he left the land as it was, untouched by bricks and mortar. It suited the tenants of his properties, who now had somewhere to park their cars. All of which were deserted: only Sokrati's family were up that night. Sokrati put it down to no one else having had as many big earthquake experiences as himself.

But strange things happen at that time of night. An

agrotiko* drove by, the first of only two vehicles to drive down their road during the hour that they were waiting for the next tremor (which never came). The same car returned and parked on a side street leading off the main road, adjacent to the car park which was situated on a corner. Now they both had a clear view of the driver, as he got out of the truck. He lit a cigarette. The fire from the cigarette lighter flashed close to his mouth, giving them a good look at his face. It seemed as though he was waiting for someone. Sokrati realised that the man had probably seen them sitting in the car. But the man did not seem to be perturbed by their spectator status; he probably thought that they were lovers, and they were waiting for him to disappear before they began their frolics. Cheap hotel rooms had suddenly become very expensive during the crisis. Rania also understood that the man had seen them watching him. If he didn't think they were lovers, then he must have thought they were nutters. Either way, he didn't look concerned.

Then a Fiat Punto appeared on the street. It stopped at the front door of the apartment block. Rania and Sokrati were somewhat surprised to see the tenant of an apartment on the first floor of their block coming out of the car, a not very attractive Hungarian woman, who had recently moved to the town from Arta. During her first month of renting the apartment, she had told Rania that she was a cleaning lady who lives alone. Throughout her short term of residence in their apartment block, she had already created problems by not paying her heating bills and

rent.

"I always thought she had a night job," Rania whispered to Sokrati. "There's no shortage of cleaning ladies in this town."

"Now we know it for sure," Sokrati whispered back, after checking that the children were asleep. The woman opened the main door of the apartment block (it was never locked) and disappeared up the staircase. The old man who was driving the Fiat Punto drove away. The agrotiko driver got out and entered the building. He was obviously going up to the woman's flat, which by now had lit up the darkness of the wee hours of the night.

The woman looked out of the window and spotted

Rania and Sokrati sitting in the car.

We are officially nutters, Rania thought.

"She

can't be very successful in her night job," Sokrati said. "She's still not paying her heating bills."

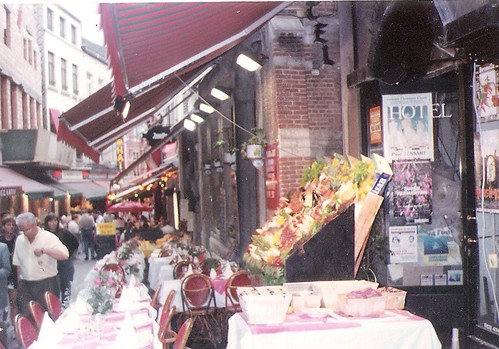

Red light district, Minoos St, Hania; note the number of air-conditioning units: the rooms must get really steamy

They were not completely surprised with the events that unfolded that night. Next door to their flat lived a 50-year-old spinster who was having great success

with young men. They had seen her on other nights getting in and out of her apartment,

waiting by the front door in her nightgown. But tonight, she was quiet; possibly she had scheduled her visitations better, giving her time to sleep at a normal hour.

"The neighbourhood's quite lively at this time of night, don't you think?" Sokrati chuckled.

"Just think how much time we're wasting," Rania replied. Sokrati looked at her suspiciously as Rania frowned back at him. "These guys seem to be doing over-time while we're peacefully

sleeping on the top floor every night instead of working," she added.

"They suffer from the classic Greek problem," Sokrati reflected. "Their productivity level doesn't match their output." Rania laughed, making a minimum of noise, with the children in mind. Although Sokrati can be a total geek at times, he still has a good sense of humour.

"You can't hide in small places," she mused.

Sokrati smiled. "Well, I think it's more of a case of Greeks showing their true selves in this crisis. We're doing a good deed providing shelter to this gypsy. We should send her more customers so that she'll be able to pay at least the

heating bill."

"Μπα, she must be lousy in all her jobs. We clean the stairs

more often than she does," said Rania. "Which is like never."

*agrotiko = pick-up truck; usually owned by someone whose main occupation is farming.

*** *** ***

Just for the record, I don't live in an apartment block, or in the middle of town, and there is no car park located by my street. According to my cab-driver husband, the oldest profession in the world has seen a revival in this little town.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically

cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any

means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.