"Don't do it, because if you do, θα σε κάνω τόπι στο ξύλο," my mother often told me. I must have done whatever she told me not to do very often, because I remember eating a lot of wood when I was young. It always came in the form of footwear. I can still picture my mother taking off her slipper - the open kind, the fashion we call 'mules' these days, in a powdery blue colour, with a rounded toe and synthetic fur round the edge - and directing it onto my legs. If I remember correctly, it would leave a red imprint on my skin for at least two days.

Eating wood was once very widespread in Greece; most kids ate it at some point in their life. Although it wasn't the norm to feed Kiwi school pupils wood, in 1970s Wellington, quite a few kids knew what it tasted like. Take Mrs Fa'alofa* at my old primary school: she didn't like it when kids swore. She probably meant it when she told her class that if she heard them use bad words again, she'd wash their mouth with soap and water. This applied to everyone, except the Fijians. You see, Mrs Fa'alofa, being Fijian herself, knew that a serving of wood could also be applied - but only to her own kind, of course.

The school rules also changed after half-past three, when the Greek after-school language program began, in the same building as the one the children of Greek immigrants attended during the day, where they did their lessons during regular school hours in the New Zealand state school system. At half-past three, the Greek school teacher would come along, and when the children did not perform well in reading and writing Greek, or when they were naughty, rude or disobedient, the teacher would resort to the same system used in Greece to bring order back to the classroom: s/he would bring out the βέργα. In Greece, this was usually a long slender cane cut from the branch of an olive tree, denuded of fruit and leaves. The teacher would ask the child to stretch out its hand, and the βέργα would make a whipping sound as it came down onto the child's palm. In New Zealand Greek school, there were no olive branches at the teacher's disposal, so a ruler was used instead. It was just as effective. And no one ever complained or thought it inappropriate; they were probably used to it at home anyway.

But unlike in Greece, the tide was turning against wood eating, not just in public places, but even in private homes. One day, Rallou came home from school and told her father that, from now on, if the Greek school teacher forced a meal of wood on her, she would tell her English school teacher, and the Greek school teacher would go to jail. Not that Rallou had ever been given wood to eat from any teacher; she was a very good student with nice manners. Her dad, like most Greek dads, didn't do the cooking in the house; Rallou's mother did, and when she saw fit, she whipped up a batch of wood for any of her children whenever necesary.

Stelios enjoyed having his children tell him how they spent their day at school. He liked to ask them about what they learnt, so that he could learn about those things too, because he did not have the opportunity to learn a lot in his school days, as they were cut short by the war. But this was not the kind of thing he had expected his children to be taught at school. "Come again?" asked her father. "Why are you telling me this?"

Rallou explained to him that in today's lessons, the teacher told all the pupils in the class that no one in the world is allowed to hit anyone else, and if anyone hits her, and the teacher meant anyone at all, even her own parents, then she has to tell her teacher, and the teacher will tell the headmaster, and the headmaster will tell the police, and the police will come and take the person who hit her to jail, and they wouldn't be allowed to hit her ever again.

Rallou's dad was a very easy-going chap. Stelios never gave anyone any trouble. He smiled and laughed a lot, especially when he arrived in New Zealand, because he could tell, immediately on landing in this new world, that it was nothing like his old world, and that in his new free life, everything was going to be good (except maybe the weather), a fact that alleviated the wounds that his old life had left him: faint scars from the time when he was being chased by the Nazis because he had stolen their telegraph equipment and given it to the Cretan resistance fighters, and the Nazis came to his house looking for him and his father, who had dressed him up in his sister's clothes, and put a pail in his hand and told him to pretend that he was going to the chicken coop to find some eggs,while his father escaped - in his grandmother's clothes - through a window. When Stelios came back two days later, he found only the stone work of the house upright, guarding the smoldering remains of the rest of the house which had been set fire to. His mother and siblings had taken shelter in the neighbour's stables; his father was never seen alive again.

These houses (Vathi, Hania, Crete) were abandoned after they were set fire to during WW2.

The story his daughter told him made him raise his eyebrows. He could not believe what he was hearing. Since he did not tell anyone what to do in their house, he expected this respect to be returned by people when they were in his house. Although the teacher was not in his house at this very moment telling him what to do and what not to do, his daughter's announcement struck him as an invasion of privacy. He did not like to have the finger pointed at him, like a suspect in a criminal offence, when he had never even committed the crime in question in the first place.

So he took a piece of crayon from his children's stash of colours, moved the table and chairs to the wall, and drew a map of Crete on the wooden floor of their kitchen. He called Rallou, who was in the living room watching Sesame Street with her brother Kosta.

"Can't it wait, Dad?" Both Kosta and Rallou liked Sesame Street (they had grown out of Play School).

"Come her right now, both of you," her father shouted, something he did not do much at all in the house. The children subconsciously knew this quite well, because it was the tone in his voice that aroused them from their semi-drugged state of mind as they were watching the box. This tone sounded rather frightening. They rushed into the kitchen to see what was happening, where they found the furniture rearranged and the drawing on the floor. Indeed, something serious was taking place.

"Come on in, both of you." Stelios spoke firmly. "Step inside," he said, pointing to the map he had drawn on the floor. "There's room for all of us in here." He placed his feet within the borders of the map.

"Have I ever told you what to do?" The children did not initially respond. They stared at the fatehr with confused looks on their faces.

"Have I ever hit you?" he asked them both.

"No," the children answered almost simultaneously. They knew the answer to that one, and did not need to confer with each other to agree on the correct response here.

"Το ξέρετε ότι το ξύλο βγήκε από το παράδεισo?" Stelios asked them.

The children probably didn't know this, but they would never have suspected that the words 'wood' and 'paradise' could be collocated anyway.

Stelios continued. "Maybe you just don't know how good your life is, then!" And with that, he grabbed each child from the one arm, and whacked their bum with his hand.

The children began crying, which was only natural. When their mum fed them wood, they usually knew why they were being served it. Today, they couldn't make sense of the situation.

"But what did we do?" they pleaded.

Their father was not listening to them. "Now, Rallou, you go ahead and tell your teacher. And don't forget to tell her that you were standing in Crete when this happened!" And that was the first and last time Stelios ever gave his children wood to eat.

*** *** ***

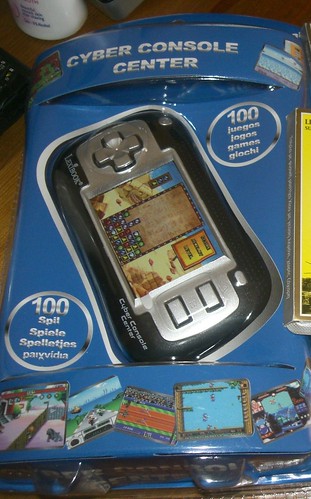

Nowadays most of us prefer to discipline our children by other means, eg taking away their internet rights and/or gameboys, grounding them, not allowing to have friends over or to visit them, etc. A good one in the hot weather is 'no ice-cream'. These are all forms of synthetic wood, and they feel a bit like a substitute for the real thing. I resisted investing in these until only just recently. When I let them play with them, I get the feeling that the children aren't in the house at all.

Sometimes these substitutes have the same value as junk food: the effects of bad nutrition are similar to the effects of ineffective punishment. They are wholly inappropriate under certain circumstances, like when a child rummages through the drawers in his parents' bedroom and finds a small sharp blade that he places under his bum to hide it as he's sitting on a chair, just as his mum serves him lambchops for lunch. When he squeezes some lemon over his meat, and the juice splatters into his eyes, he cries out in pain and rushes to the bathroom to wash his face. The parent (the one who stayed at the table while the other accompanied the child to the bathroom) who discovers the blade lying innocently on the chair will probably have a heart attack before he manages to reach the bathroom to check if the child's affliction really was caused by the lemon juice, or if it was something else. The child's next meal will probably contain a good solid serving of wood, no artificial flavourings or colours added.

Just like Rallou's dad, my dad never EVER ever gave me wood to eat, but I do remember once (I was a pre-schooler) when he gave me a plate similar to what the waiter gave this little boy (mine contained soup, not makaronada). Wood was also being served at this restaurant - you can see the waiter eating quite a bit.

Bear in mind that under current laws, feeding wood to your kids is actually prohibited by law in Greece just like it is in New Zealand, as is speaking on a cellphone while driving, not wearing a helmet while riding a motorcycle and not smoking in public places, but it is controversially contested as a law, both in New Zealand, and in Greece, whereas the other infractions of the law are not. Fake servings of wood can also become contentious issues, especially when unknown customs are brought into play. But there were also times when eating wood became a form of survival.

*not her real name

Thanks to Nikos and Alekos for some of the ideas that I wove into this story.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

I always enjoy your posts:))

ReplyDeleteSo you found out about 'op een houtje bijten' (biting a stick).

ReplyDeleteI wish people stopped abusing eachother, children, animals, the planet and themselves.

Θα φας ξύλο is the version we got in South Chicago :)

ReplyDeleteReally enjoyed the text with all this wood eating. Do you know what the problem is with today's parenting? Our children spent too much time indoors.

ReplyDeleteΧε χε, Great post!

ReplyDelete