And here's the grand finale of my family's recent adventures in Athens. Two years ago on the

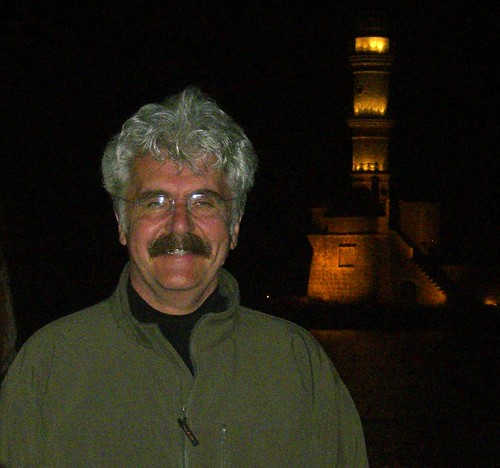

25th of March, we found ourselves in London, and we did what all good Greeks would do on that day, even if they find themselves outside Greece: we attended the church service in the Greek Orthodox Church Of

Agia Sofia in Bayswater. The

25th of March is a dual celebration for Greek people: it is both a religious holiday (the Annunciation of the Virgin Mary) and a national holiday (Independence from the Ottoman regime in 1821); hence, it is considered the most important national celebration.

This year, we found ourselves in the centre of

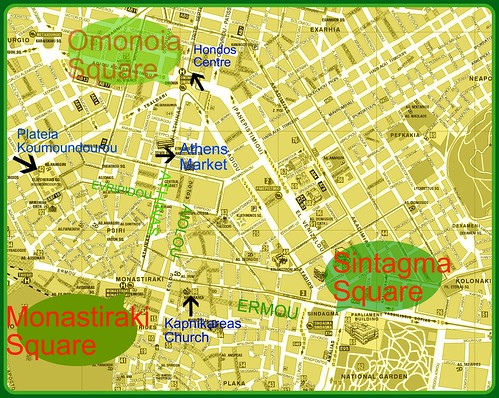

Athens on that same day, not a particularly good one for ticking things off a list of things that you intended to do in Athens on a limited stay: everything is closed, as well as blocked off. On this day in Athens, the most important military parade of the year takes place immediately after the church service ends between two of the most central squares in the city:

Syntagma (Constitution Square) and

Omonoia (the Greek version of Times Square, translating to "Place de la Concorde"). The parade in Athens takes place rather differently from the other parades that take place around the country (and

every town, village and suburb has its own parade on that day). Normally, schoolchildren are part of the parade, but because Athens is the capital city of Greece, the parade takes place over two days: on the eve of the celebration, the schoolchildren take part in their own parade, while the next day is devoted to the military parade, a state-organised event. Never being a fan of displays of nepotism, I felt my last day in

Athens would go wasted.

Children were waving the Greek flag; this kind of display of patriotism was never a part of my Kiwi upbringing. A black man - well, he was

very black, nothing compared to the skin colour normally encountered in Greece - was selling flags on the street; I bought two for my children. I felt out of place here. But what were half the spectators feeling, who weren't even

Greek? Some had the distinct features of a different race, notably skin colour; the darker shades were probably from Afghanistan, Iraq or Pakistan (at least that's what

Landomircales claims they are), while the paler blonder spectators were probably Eastern Europeans, judging by the language they were speaking; is Greece more multi-cultural than people are willing to admit? One reason why so many non-Greeks attended the parade is that the area around Omonoia Square is infamously a migrants' hangout (whether legal or illegal), especially once the sun sets.

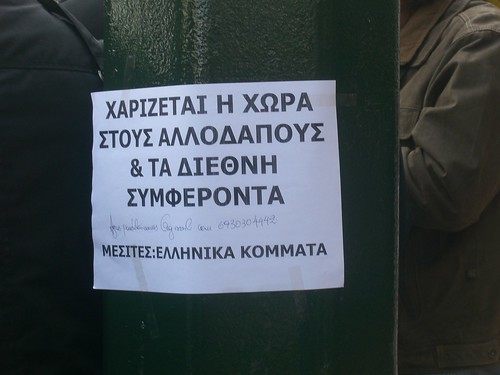

A lot of anti-immigrant leaflets were being handed around during the parade; this is only one example: "The country is being given away for free to foreigners and international interests;Real estate agents: Greek political parties". In Hania, things are less damning for the economic migrants, but racist undertones still exist, mainly in the classified ads of the local newspaper, along the lines of: "Apartment to rent. Not for foreigners", or "Barman/woman wanted - must be εμφανίσιμη - emfanisimi' (good looking) - only Greeks should apply."

There are many things being said about the presence of foreigners in Athens and the rest of the country. Generally speaking, people don't have a lot of nice things to say about them. It is common practice all over the world to despise, criticise and look down on people who may be seen as uninvited guests, a kind of invading force in an old established country with a racial homogeneity of more than 90%. Having been raised in a liberally-minded country, I find it highly egotistical to think of a supreme race of Greek citizens that does not include people of all colours, especially since Greeks themselves migrated to and were welcomed by different countries all over the world for economic reasons. Legal migrants sound like a good idea to populate a country that has a very low birth rate. Unfortunately, a high number of these people are illegal immigrants, and the state is clearly not doing anything about it; the lax authorities are the ones who should be rounded up and punished.

*** *** ***

We managed to catch up with the parade just as the last army vehicle passed by (a tank), followed by some kind of vessel used by the Navy. A few police cars and motorcycles then drove by slowly enough for everyone to show their despise of authority; only half a dozen people clapped (I may be over-estimating). I'm sure these guys do their best, but sadly, their best is simply not enough these days to defeat the increasing crime rate in the capital of Greece. Not a day passes that we don't hear about a murder, mugging, attack or some other ill taking place in various parts of the capital, more so now than at any other time in the history of modern Athens.

Planes flying in formation over Omonoia Square

Planes flying in formation over Omonoia SquareA long time seemed to pass without anything happening on the street. That was when we heard the sound of an overhead roar as planes flew in formation above our heads. We could only catch glimpses of them as they suddenly appeared in between the small open spaces enclosed by the tall buildings around the square. During this quiet spell in the parade, I was able to observe my surroundings a little more closely. Glued to the wall in the most prominent places (building walls, signposts, etc) were proclamations against the presence of foreigners. Leaflets were scattered below our feet expressing similar opinions. The foreigners (many of them) walking up and down the street paid little attention to the flyers and posters denouncing them; they probably couldn't read Greek.

After what seemed like ages, we finally heard some band music making its way towards us. This was when things picked up and became more exciting. The sight of the young men and women looking very smart in their uniforms caused a flutter in the hearts of most of the spectators. Everyone clapped their hardest as soldiers marched with stern faces down the street. These people are in the prime of their youth, and it is a well-known fact that they are in charge of looking after the borders of our country, a job they do very well. By watching the parade, I felt that I had seen our guardians close up, as if I had personally met them. There were even a few black men marching in Greek military uniform, a noteworthy point if anyone wants to argue for a homogeneous Greek race, or debate whether black people should or should not be living in Greece.

My husband recalled the years he spent marching in the parade. Being tall for his age, he was always part of the national day parades during his school years in Hania, which also continued in his three-year army stint at

bootcamp. He particularly remembers the antics of his fellow soldiers who weren't taking part in the parade, but were simply watching from the side of the road. They had filled their pockets with pebbles and small stones, and would toss them at the metal hats of the paraders when no one was looking.

Clink, clink, clink all the way home.

An unexpected twist was my daughter's reaction to the parade. She was impressed by the many women also marching and expressed a desire to be the proud wearer of one of those uniforms; it was hard to choose just one! (A career in the military still sounds too regimental to me.)

The moment in the parade which received the most applause was when a group of special forces walked by chanting loudly:

Έχω μια 'δερφή! (I have a sister!)

Ειν' αληθινή! (She's genuine!)

Μακεδονία την λένε (Her name's Makedonia)

και την αγαπώ πολύ! (and I love her very much!)

I abhor nationalism, but I couldn't help feeling slightly moved myself at this point.

*** *** ***

At the end of the parade, we joined the masses of people leaving the parade, forming an orderly queue, except that at the end of the line, there was nothing to take.

No one stopped this fellow from joining in the fun;

at the end of the parade, the spectators walked behind the last marching band group.

Everyone looked as though they had somewhere to go, even on a day like this one when there was nowhere to go. Athenians don't smile much on the street, but not because they are unfriendly; the city has become a bit of a

hell-hole for the ordinary citizens who live and work there on a daily basis. Ask an Athenian for directions, and you'll get them; if they see you carrying a heavy suitcase, they'll help you. The fact that

Athens has lost its 'safe house' status in just the last few months has made the inhabitants weary. They are tired of being savaged by the traffic, roadworks, strikes, protests, pollution, slow or non-functional transport system, and generally, the fear of not knowing what one will encounter when they venture out of their house to go to work or get a job done.

It was an eerie feeling walking amongst so many people in central Athens, while all the shops were closed. It was as if the parade hadn't finished; everyone marched away in quick steps - no dawdling around the streets of Omonoia. It was almost lunchtime, and we were all thinking about food, not because we were particularly hungry, but because food forms a central part of a holiday experience. So we began to look for a cosy place to sit down and eat. The weather was moderate but cloudy. Not being locals ourselves, we moved in the direction of

Psiri, a popular area for eating out in central Athens.

I like to wander through narrow side streets away from main routes; a bit of sightseeing off the beaten track. We turned off the main road and eventually found ourselves in

Evripidou St, close to the central fruit and vegetable market in Athens. As it was a holiday, nothing was open, but there were still throngs of people walking along the road. At one point, we ran into a large group of black men, no women, no children, just men, black men, lots of them, maybe too many for such an old narrow street in central Athens. Our presence there looked out of place; we turned away from this crowd in search of something more familiar to us.

At one time, this may have been a very grand mansion; now it is an earthquake risk sitting in a central position on Evripidou Street. Where are its owners to give it some TLC?

At one time, this may have been a very grand mansion; now it is an earthquake risk sitting in a central position on Evripidou Street. Where are its owners to give it some TLC?I don't normally feel intimidated when I find myself among people of a different race or colour, but this situation didn't feel right; it actually felt ridiculous.

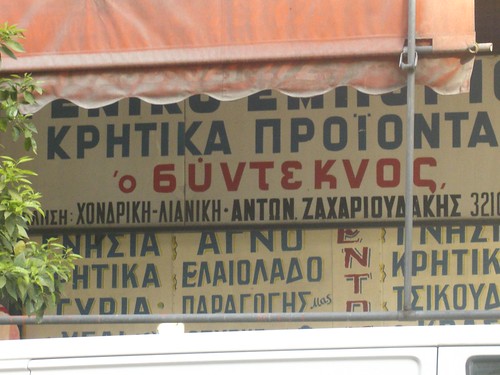

Evripidou St is normally a busy commercial district with a bustling market atmosphere, reviving memories of old Greek films with its narrow pavements which the store owners use to display goods. It is also filled with bumper-to-bumper traffic. Despite its significance, it is one of the filthiest streets in central Athens. Derelict buildings look as though they are about to give way any minute (not a good place to be in during an earthquake).

We continued walking, making for

Athinas Road, which would eventually lead us into the tourist's haven,

Monastiraki, sitting below the Acropolis. On our way there, a well-built blond man bedecked in leather with a highly pierced face (there were holes filled with silver bits all over it) asked us in perfect Greek if we could give him some money, '

even 50 cents is OK', he said. Maybe it was the time of day, or because we were a family, that we didn't get mugged. Children act as a protective sheath in a family-oriented nation like Greece. If we had been mugged that day, it would probably have been by one of our own kind.

We carried on our way (without giving the junkie any money), and finally met up with all the tourists in the

Monastiraki area, who had taken up most of the outdoor seats in the eateries there. We managed to squeeze in at

Thanasis kebab house, a carnivore's paradise. That was the wrong food for the day; food on the

25th of March in Greece is traditionally associated with

fish, not meat, as it always occurs during the Great Lent of Easter. The kebabs were delicious nonetheless, but at this point, I was glad I was going

home.

*** *** ***

I know it's not the 25th of March today; it's the 25th of April, ANZAC Day, a public holiday down under, commemorating the contribution of the Australian and New Zealand 'diggers' who fought in Gallipoli, Turkey, in the Great War, what we commonly refer to nowadays as World War One. ANZAC biscuits were created during this period to send to the soldiers fighting for the cause. Since they contain ingredients that do not spoil easily (these cookies do not contain eggs), they could survive the journey half way across the world. Both New Zealand and Australia claim rights to the original recipe. As the word 'ANZAC' is heavily loaded with nationalistic feelings, it cannot be used with any other biscuit that does not resemble the original recipe. This is a rare form of censorship coming from a very liberally minded country like New Zealand, a clear sign that the military is not to be taken lightly anywhere.

For 30 biscuits, you need:

1 cup flour (I found I needed at least 1 1/2 cups to get the right biscuit dough texture)

1 cup sugar

1 cup rolled oats (I used a muesli mixture instead)

1 cup desiccated coconut (I didn't have any in my pantry when I made these cookies, so I used extra muesli - they are much crispier and tastier with coconut, even though this ingredient was added to the recipe more than a decade after ANZAC biscuits first appeared)

175 grams butter (I used margarine)

2 tablespoons golden syrup (a uniquely colonial ingredient)

1 teaspoon vanilla essence (in Greece, vanilla sugar is sold in small vials)

1 teaspoon baking soda

2 tablespoons boiling water

Preheat the oven to 180C. Lightly grease 1 or 2 baking trays or line with baking paper. In a large bowl, sift flour with a good pinch of salt. Stir in the sugar, rolled oats and coconut and make a well in the centre. Add the melted butter, golden syrup and vanilla essence together. Dissolve the baking soda in the boiling water. Mix into the melted butter and quickly pour into the well.

ANZAC biscuits - lest we forget

ANZAC biscuits - lest we forgetColonial New Zealand recipes tend to contain very basic ingredients. It took a long time for imported products to reach the early European settlers in New Zealand, so people relied on more basic ingredients when they first started creating home-grown recipes. The

recipe I used to make these ANZAC biscuits comes from New Zealander

Allyson Gofton's collection, with slight variations (thanks to my cousin for the recipe). These biscuits are very tasty. Nothing like a Greek

koulouraki, but probably much better for you than the average Greek sweet, as they don't contain eggs. The golden syrup sweetens them quite a bit and helps them to keep their shape once they have hardened. They are also very easy and quick to make and bake, reflecting the

carefree nonchalant (albeit at times

overly politically correct) New Zealand attitude to life, the universe and everything. My absolute favorite New Zealand biscuits are

gingernuts and

afghans.

Talking about New Zealand sweets, let's not forget the great New Zealand

pavlova - unbeatably refreshing in the hot weather when served with fresh fruit. If I couldn't reproduce these sweets in my own home, I'd get quite homesick. Which reminds me, I'm almost out of

golden syrup.

.