“Come on you. Let’s go you, people are waiting.”

Quote from "America America" by Elia Kazan

Immigration is high on the agenda of the global world these days. Not all doors are open though; some doors are even having walls built over them so that they can never open. Βarriers to immigration have been coming up and down over the years, so Trump's (physical) wall and Brexit's (figurative) wall are not new in this respect. (

UPDATE 14/6/23: Greece has built a big huge one too.) As 'special relationships' begin to disintegrate, even race and wealth factors don't factor into the barriers: the doors just try to stay shut, as in the New World (places like the US and Australia) which is trying to limit immigration. There are reduced employment opportunities now for the growing population of the world due to automated technology which has changed the job market, coupled with the situation where people who are looking to migrate for better opportunities in life are all trying to get to the same places. But it pays to remember that in the world's history, there have always been periods of limiting migration and periods of opening up opportunities for it. At present, we find ourselves in the limiting part of the cycle.

If my parents were still alive, they might be bewildered by this: they migrated at a time when migration was very common. "Don't forget us," my father said to his friend as he left Greece on a ship from Pireas bound for Wellington. His friend settled there with his wife and children. Eventually, they met my mother who was visiting Wellington while she was working in a boarding school in the small agricultural town of Fielding 160km away. My mother had a two-year contract to work there, after which she could choose to stay in NZ or go back home. But before the two-year contract was over, she was already married to my father in NZ, with my father's friend acting as best man.

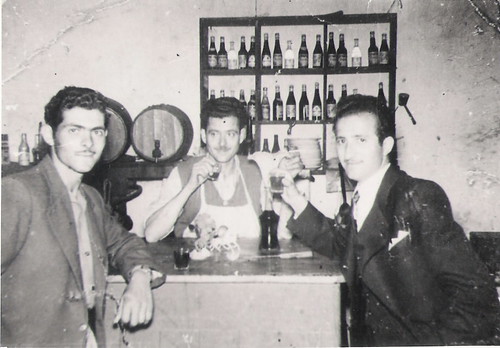

Dad - left - as a teenager at Keratas taverna in Platanias, Chania, Crete

My parents never met in person until a week before their wedding. They got to know each other through my father's friends, photographs, and letters they wrote to each other. My mother kept this 10-month long correspondence with my father, which I found after their deaths, and I decided to read the letters only recently. (My father's letters stayed in Greece and were probably thrown away.) Although they are in essence love letters, they told me much less about love than about commitment, compromise and assurance. The fifteen letters in total (an excerpt from each one in consecutive order is included in this post) reveal the novelty and excitement of getting involved in something completely different, as well as the fear of leaving not so much one's homeland, but rather, leaving behind the most important people in one's life, their immediate family members. The letters are really about the pain of making the decision to emigrate for a better future, while their immediate past keeps chasing them back.

My parents didn't finish primary school, but they were literate in the way that most people of their time were literate: they could read and write, but didn't necessarily spell words according to standard Greek spelling rules; they rarely used stress marks or punctuation: no commas, no full stops; new lines indicated a new paragraph or idea, while capital letters often highlighted words or they were used randomly at the beginning of a word. But they wrote in a way that anyone could read their letters: as long as you can read the Greek alphabet and understand basic Greek grammar, you would be able to understand their letters. Even my mother's mother was literate in a similar manner, from the one sample I have of her writing (she received many letter from her children in NZ). The only real difference between my father's and grandmother's written language skills is that my father wrote words using standard Greek pronunciation, whereas my grandmother wrote everything as it would be spoken in a Cretan accent.

My father's letters always started and ended in the same way, a hint of the importance of the formalities at the time in Greek letter writing. You always ask about the recipient's health at the beginning of a letter:

My dear Zambia, gia sou. I hope my letter finds you (singular) in full health and happiness in the same way that I am well and happy, at the time of writing. Dearest Zambia, I received your letter and I read your news with great happiness and was glad to hear that you are well.

... and you always send greetings to them at the end:

With this news, I close my letter. You have lots of greetings from D., M. and children, and all the cousins that are here. Send my greetings especially to our little sister (my mother's sister who was also living in NZ). Regards with love, your future husband, Manolis, gia sas.

The letters (and a card) that Dad wrote to Mum

My father was writing his letters from Athens, in the port town of Pireas, to my mother who was living and working in NZ. But in that year of correspondence with my mother, he travelled regularly to Crete. Crete was the reference point of all his letters:

Last Saturday I went to your house and met your respectable parents and I left a ring, the ring which will unite us for ever. I hope they wrote you all the details. I am very happy in general with all your relatives, parents and brothers, they gave us a huge welcome, even though you were not there. The truth is that that particular night was really rather sad but with God's will, everything will be forgotten one day.

The sadness of the event was not so much that my mother didn't attend her own engagement party; it was because she was not in the country. In my mother's case, the need to emigrate was greater than the need to find a partner: my mother was the oldest among her siblings and her family was very poor, too poor to marry. An arranged marriage would be a much easier way to find a partner than to wait for Mr Right to come along. Poor girls were not seen as desirable - except to poor men:

I noticed that you wrote that you have understood that I am a good man. In this way I have understood that I have found a truly good girl to live with in love and happiness for the rest of my life, as it has been determined by the all powerful God.

What's a poor man to do in a country that could not provide for him? My father realised that he would be leaving his family soon:

Zambia, I have ordered the wedding rings in the size according to the little paper that you sent me in your letter. Concerning the issue of the invitation [to come to NZ] which you wrote about, you say you have to spend a year [in NZ] to be entitled to get the invitation process going, and I have been told that it takes a long time, so the earlier you start it, the better.

Immigration involved a lengthy waiting period, which does not seem to be too different from our times. Applications are processed one by one, on a case by case basis, they go through different offices and officials, and the process can seem drawn out:

Two days ago I came back from Crete and I read your lovely letter and I am very happy to see that you are well. I didn't write immediately because I was arranging to fix (ie fill in) the documents you sent me but I was told to ask and find out what to write in the question where the paper asks me to complete some information I don't understand, so I to our koumbaro A. to tell me what to write. Surely he too will have fixed such a document and he will know, in case I make a mistake. I will wait until he replies before fixing it. I am waiting for his reply. Better to delay it a little than to make a mistake and need to redo it.

While you wait for the process to catch up with you, you do a lot of thinking. Doubts cross your mind when you suddenly realise that what you are about to do, but the need to maintain stability in your life overrides the fear of the unknown:

So my dear Zambia, I will fix the paper that you have sent me in the way A. told me to do it in his recent letter, and I will send it to you. But before I make these plans for the invitation, I want you to write to me about how life is there, and if it is like here. There is no reason for me to leave, and for the two of us to live alone far away from our own people, if you can come back here instead, I am not going to go back to the village except for a volta (short holiday). I can work here [in Pireas], I can earn a little or a lot, we will live according to our class, but again if you see that we can be better off there, I may as well come, to stay for a certain period of time and then we will see. I can't write anything else to you about this, because I don't know where is better. But you've lived here, and you are over there now, you must have come to some conclusion where life is better, and to act accordingly. Ι will send you the paper and I will wait for you to write to me what you are going to do, if you will start the procedure for me to come or if you will come back here. As you wish, I leave you to your will.

There is a clear sinking feeling in my father's letter that he has no other choice but to leave. This is confirmed in his next letter:

I note that you wrote that of those who have gone there (NZ) some like it, whereas others don't. I want to find out if you money remains (you don't live hand to mouth), to save some money so we can return here and do something (set ourselves up). That's why I wrote to you to tell me how things are there because if we are to work and just make ends meet and not be able to earn the money for the return tickets, we may as well stay here (Greece). That's why I wrote to you. At any rate, A. wrote to me that I would be earning 80 pounds a month and if this is so, it sounds good. You asked me to write what job I do and how much money I make here. Wherever I go to work, they say they will pay you 64 drachma as a basic wage. I was working at the port and getting 650 to 700 drachmas a week but they cut my number of working days since Christmas so I am going to go and find work where M. is working, whenever they need an extra hand. Since Easter when I returned from Crete I got a job at the ship repair yards and I was making 58 drachma clear there but I had also fixed my papers to get a job in a factory which makes refrigerators, stoves and other things (ΠΙΤΣΟΣ) and they informed me to go, so I left the ship repair yards, and I've been at the factory since last week, but I don't know what fees they will take off my wage (ie taxes) and I don't know what I will clear, but whatever job anyone has here, life is very difficult for those who do not have a home and are renting.

Having your own home has always been important to Greeks, and never more so than now in difficult times. It seems that it's also important to most people in the world judging by the value of house prices in western society, but there is a clear difference between owning a house in the New World and owning a home in a country like Greece: the house where a family lives is never seen as an investment property, it is always regarded as a home that will always be in the possession of the same family. It can be divided up into smaller homes to avoid rentals for future generations, or it can be passed on to one child while other children inherit something else, eg an orchard or olive grove. Post-WW2 village life - where more than likely there was a family home - was clearly not viable for both my parents: my father did the odd job for wealthier relatives while my mother was an olive picker who was not always paid for her work, so they both migrated to the capital city eventually. Dad found port and factory work, but Mum went to Athens only to do a paid training course in housekeeping and English language learning in preparation for emigration. If they could have secured their own home in the capital city, I think they would not have left Greece. And here lies another big difference between the Greek 60s migrants and the neo-immigrants of today: the rural poor - people who literally had nothing to lose - were emigrating in the 60s, while in our times it is the educated urban class, who often maintain home ownership in Greece (among other income earning assets), that are emigrating.

Sometimes, there was nothing new for my father to write to my mother. So he would ask her about the the progress of his case in the immigration process:

Zambia, I noted that you wrote that you went to A. who told you that he wrote to me. Could you check if he has sent in my papers, if he hasn't done so already, because I hear that it takes a long time for the officials to start dealing with them. And please ask him to tell me the date he sent them in, so I can ask when they will arrive approximately.

It sounds like he was in a rush to leave. Reading between the lines, I think he was just feeling the pressure of the waiting time. He mentions the same thing in the next letter:

My Dearest Zambia, I don't believe you will misunderstand me for writing back so late but this delay happened because I received a letter from the British embassy and they were asking for some documentation from me and I went to Crete to get them and I then came back to Athens and they sent me from one office to another until today when I was checked by some doctors and now, I've finished with all this business and all that remains is the notification for me to come. That's why I hadn't written to you and I know that this would have worried you but now that you have read that everything is ok, you will be happy and all your worries will be over. I was worried too until today when I arranged all the papers.

But he didn't stop writing to my mother, even when there was no new news:

My most beloved Zambia, gia sou. I hope my letter finds you in full health and happiness as it leaves us. My Dearest I received your letter and I am glad that you are well. I noted that you wrote that you are waiting for a letter from the embassy. Well, when you receive a letter, write to me and tell me what they say. From here, I have no other news to tell you...

I remember my mother saying that she would never write more than one letter back to her prospective husband: it was always get-one-letter, write-one-back. I remember her telling me this as she laughed about it: "I didn't want to be taken for a ride". And my honourable father knew this, so he kept writing, even when he didn't have much news to write about. It is said that when you don't do much, you start meddling:

My Dearest I received your letter and I am glad that you are well. So, I got a letter from A. but he didn't write anything about what you wrote to me, about sending me an address so I can go there and ask if I can leave earlier. I am wondering where he went, so I can go and ask too, because I go to the embassy to ask and they say they don't know.

My father was feeling the pressure of the time passing, in other words the time being wasted, when what he wanted to do was get on with the life he had been planning:

Well Zambio mou, yesterday as soon as I arrived from Crete I read all the letters that had arrived and immediately I went with that man who A. had written to me about, together with a clerk at the embassy, and they told us that as soon as the conditional visa comes, they will inform us. Well, that man who A. told me about told me to write to you not to pay any money to anyone until I get that conditional visa so that he can fix my passport, and later, we will send you the address of the office of the representative of his agency so that you can go with A. to pay the costs of my journey to come over. I asked him about the price of the ticket and he said that there's a 3,000 (drachma) difference between the plane and the ship, but you will arrange what's best, I don't mind how I come.

We can surmise from the above that there were charlatans everywhere. But what most excited me was the different journeys available in those days: you could take the slow cheap one by boat, or you could take the fast expensive one by plane. These days, a long boat journey would be classified as an expensive cruise holiday while budget travellers book lo-cost airlines.

Dad's first few months in New Zealand, with Mum - left - and the "little sister"

Dad's first few months in New Zealand, with Mum - left - and the "little sister"

The end of the waiting time was fast approaching; preparations for departure were now beginning:

I was late in writing back to you because I was in Crete and D. sent your letter down to me and that's why I didn't write from there (in Pireaas) and now I came back on Saturday and I went to T. about the chest you wrote about that you wanted me to bring to you, and he told me that I can take only one suitcase with a maximum weight of 20kg, just like you already told me, so I will send the chest by ship which will leave from here on 2 February for New Zealand and it will arrive in a month. Now concerning my arrival, I don't know when I will come because A. wrote that he went to the embassy and they told him that they have sent the required documents for me to get a passport issued and I went to the embassy here and they told me that it hasn't gone there yet and when it comes they will inform me.

And that moment eventually came:

So, I want you to know that today I am going to Crete and I will return on the 10th of the month because they told me that I will leave some time between the 15th of the month to the 20th, now which day exactly I don't know, however they told me that by the 20th, I will have left. They told me that they will inform you and you will know which day I will come. That's what they told me at the agency. And as I already wrote to you, I won't be able to take more than 20kg, so concerning the things you wrote to my mother about, my folks will send them to us by ship.

Dad finished that letter with a post-script:

PS: Dear Zambio I had writtten the letter in Athens, but I hadn't got round to sending it so I am posting the letter from Crete. I am leaving Crete on the 12th of the month and then I leave (Greece) whatever day they tell me. I am coming soon. In any case, everything is ok now.

Of course, everything worked out fine, otherwise I wouldn't be writing this story:

Well, Zambio mou I know that you are worried I am coming later than we had agreed, and that's why I am writing to you. If my letter comes before I come, you will be comforted, I know, I am going through the same feelings, because they told me that I would be leaving by the 20th of the month and I went to Crete and I came back with your brother here (to Athens) and we have been here now for 8 days and today they told us that I will leave on the 26th of the month because they told us that I would have to stay two nights in one place if I left with the earlier plane, I can't remember the placename they mentioned, and then I would leave and go to another place and stay there too, and I would have to change 4 planes to come over, but as we agreed today with the people at the agency for the plane that leaves on the 26th of the month, I will have one stop in Sydney where I will stay for 15 hours and then I will leave for Wellington but I will need two planes to get there [he was probably flying into NZ through Auckland], but don't worry, I just want someone from all of you over there, if it is easy for you, to wait for me at the airport as they told me that they will have informed you, and you will know when I will be arriving.

And yes, 'they' were all waiting for him at the airport. The letters stop here. My father arrived in NZ on the 31st of January 1965, starting work immediately at the Prestige nylon manufacturing plant in Pirie St. My parents married a week later (it happened to be Waitangi Day). I was born a year later, and the rest is history, I guess.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.