Here's a taster of the kinds of issues I will be discussing in my contribution to the First Symposium of Greek Gastronomy on Cretan Cuisine, taking place this weekend in the village of Karanou.

It wasn't that my mother didn't know how to cook. She knew how to make a meal tasty, she knew how to adapt a meal when it wasn't up to par, she could cook from pretty much anything. I remember my mother's cooking as very good work, and she was a dab hand at handling a stove full of pots cooking away on all four elements with a roast in the oven and a couple of salads under way. To think, she had never learnt to cook on a gas/electric range in Crete, but that never stopped her from recreating Cretan dishes. And she never used a cookbook, mainly because in her early years in New Zealand, she never had one. Cookbooks were unknown to her until she migrated.

Suddenly it seemed that a cookbook was indispensable. It was as necessary as, as, as sandblasted ballerinas on concertina glass-panelled doors separating the lounge from the dining room, china figurines on the mantelpiece, antimacassar crochet doilies on the armchair head and armrests. It was what everyone seemed to be buying at the time, and she wanted to add such a book to her collection of things that made her feel like the urban woman that she had become, from the rural girl that she once was. She felt the need to own a cookbook, because it represented progress.

Her husband never complained about her food, but he would often ask her to cook things that she didn't actually know how to cook. Like

Haniotiki kreatotourta. It was something she never made in her own

family home up in the mountains. She had heard about it from some other Cretan women in the low-lying village that her family moved to after their father decided to sell all the family property in the mountains. But it wasn't part of her own family's cuilinary tradition.

My mother's cooking notes

When she moved to New Zealand, she took with her a notebook where she had started to record ingredients and recipes from about the time just before she left Crete. To these notes, she added bits and pieces she had picked up form the other immigrant Greek women she met up with in her new homeland: paximathakia, melomakarona, halvas, recipes she had probably never tried up in the mountains. Her knowledge of Greek food, up until that time, consisted mainly of standard daily Greek lunchtime fare, eg fasolada, makaronada, yemista, as well as some Cretan favorites like kalitsounia. She wanted her knowledge of urban Greek cuisine to be more complete. So on her first visit back home, she went to a bookshop in Hania and bought herself a

Tselementes, which she put into her suitcase, ready to be used in her modern New Zealand kitchen.

Tselementes

After the trip back home, after she had gotten over jetlag and packed away all her things, including the mementoes and souvenirs she had brought back with her, she took out her new cookbook and began poring over its contents. To her dismay, it contained many words and concepts that she did not understand, had never heard of and couldn't pronounce: jellied ham, cold poached eggs, Mont Blanc dessert, millefeuille, among others; What on earth were these foods?!

The Tselementes was put on a bookshelf, and never used. My mother continued to cook the food she identified with, which was daily Greek fare, and festive Cretan dishes. My mother was simply expressing her identity with the food she cooked. Tselementes was trying to divert her attention away from her identity. It didn't work.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically

cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any

means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

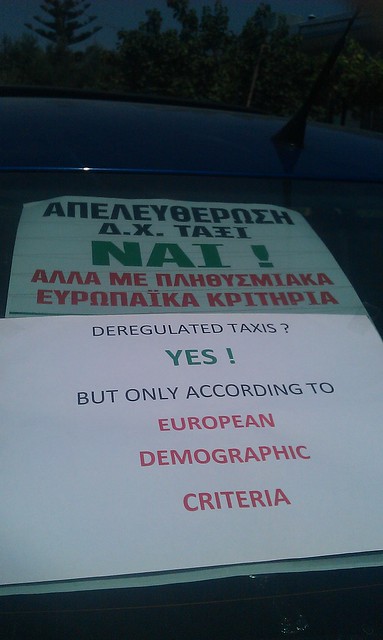

The image of summertime Greece has been shattered with the developments in my country. The economic crisis has bought on a new shame to my homeland. "The true Greek spirit left Greece many years ago with the diaspora," says a diaspora Greek, reminding us of the old-fashioned notion that diaspora Greeks have of their mother country - that she should not change, that she should be the same country she was when they left (the last large immigration wave - before the present one - was in the 60s-70s), that Greek society's evolution into a more demanding and less ignorant one somehow does not match their image of Greece, that Greece should show a more stoical acceptance of her suffering, and once again become the 'filipina' of the modern world. Worse still, even the ξένοι have realised that Greek people aren't who they used to be: "It’s crazy; Greece is the only country in the world where Greeks don’t behave like Greeks. Their welfare state, financed by Euro-oil, has bred it out of them," says Thomas Friedman. The crisis signals an end to old Greece, and the start of a new one. But where are all the good Greek people? Gone to greener pastures, Paul Whitefield says: "... all the hardworking, frugal, responsible Greeks left and came to America," he tells us. Cry, the beloved country!

The image of summertime Greece has been shattered with the developments in my country. The economic crisis has bought on a new shame to my homeland. "The true Greek spirit left Greece many years ago with the diaspora," says a diaspora Greek, reminding us of the old-fashioned notion that diaspora Greeks have of their mother country - that she should not change, that she should be the same country she was when they left (the last large immigration wave - before the present one - was in the 60s-70s), that Greek society's evolution into a more demanding and less ignorant one somehow does not match their image of Greece, that Greece should show a more stoical acceptance of her suffering, and once again become the 'filipina' of the modern world. Worse still, even the ξένοι have realised that Greek people aren't who they used to be: "It’s crazy; Greece is the only country in the world where Greeks don’t behave like Greeks. Their welfare state, financed by Euro-oil, has bred it out of them," says Thomas Friedman. The crisis signals an end to old Greece, and the start of a new one. But where are all the good Greek people? Gone to greener pastures, Paul Whitefield says: "... all the hardworking, frugal, responsible Greeks left and came to America," he tells us. Cry, the beloved country!