When my mother left her family in 1963 to go to New Zealand, she boarded a plane with a number of other Greek women, mainly from Crete. For any other woman, it might have felt like an exciting moment, but if I know my mother well, she was probably thinking about the family she had left behind: tired aging parents, two brothers and two sisters, all of whom were still in the village. Till my mother left the village, she had always lived among Cretans. Now finding herself outside her homeland, this was probably the first time my mother

actually kept company with Greek people who were not from her own

region. (Left: Cretan women working at the Wellington Hospital Laundry)

When my mother left her family in 1963 to go to New Zealand, she boarded a plane with a number of other Greek women, mainly from Crete. For any other woman, it might have felt like an exciting moment, but if I know my mother well, she was probably thinking about the family she had left behind: tired aging parents, two brothers and two sisters, all of whom were still in the village. Till my mother left the village, she had always lived among Cretans. Now finding herself outside her homeland, this was probably the first time my mother

actually kept company with Greek people who were not from her own

region. (Left: Cretan women working at the Wellington Hospital Laundry)I suppose it must have been a strange time for my mother because she was used to being close to family and village acquaintances. But I believe she was probably very relieved: these women, like herself, had left the same homeland for the same reasons that my mother had left Greece. They came from similar backgrounds - poor people, from the Greek countryside, with primary school education at the most. They practiced the same religion and they all spoke (more or less) the same language; these are the elements of their identity that they shared. Unbeknownst to my mother, this would be a defining moment in her own identity: this was when she finally became Greek, as her passport stated - before that, she was very much a Cretan.

In those days, this group of women were probably ignorant of the concept of Greek cuisine: they each had an idea of what food was eaten in their own regional cuisine, and it was probably quite different, according to the region where each one came from. Their rural isolation, coupled with little access to printed material in the form of recipe collections, and the lack of money to buy cookbooks, did not give them the chance to make culinary connections in their country. Each one cooked different food, according to the regional culinary customs they were familiar with. But when they came together in New Zealand, they were confronted with their differences; by living close to one another, making friendships on the basis of nationality, and sharing their most popular, more festive dishes in the Greek community of Wellington (where they mainly ended up after their work contract finished), they suddenly started cooking Greek food, rather than regional Greek dishes. This is about the time when my mother wanted to own a Greek cookbook, a tselementes, as we call them in Greek, after the (in)famous Greek cook, Tselementes, which she eventually bought, but never ended up using. (Right: my mother's cooking notes)

I was reminded of my mother's culinary identity only recently during our road trip through Greece last month, when I was at a taverna in Gavros, on the road towards Proussos, located in the depths of Evritania, on the foothills of the Kalliakouda mountain range, near the Karpenisiotis river. Amidst this scenic landscape, within seeing and hearing distance of the river, we had a meal at the "Spiti tou Psara" taverna.

When I asked her if it snowed as well, she had this to say: "Yes, it does snow here. But don't think it snows a lot. And when it does, it doesn't last for long. During the winter, people are able to choose between the Velouhi and Arahova ski resorts for sightseeing. They check the weather reports to see which one has the most open roads. If the television report gets it wrong, and they are misinformed, our business could go down the drain for the whole weekend. I remember hearing at one point last year that the road for Proussos was blocked with snow. We're only a quarter of an hour away from Proussos, and I could tell you that the road was quite clear. So few people passed through Gavros on that weekend. Instead of the Velouhi ski resort, they went to Arahova. That was in fact where the roads were blocked! So Arahova was empty because the roads were blocked, and Velouhi was empty because everyone was trying to go to Arahova. I call that sabotage."

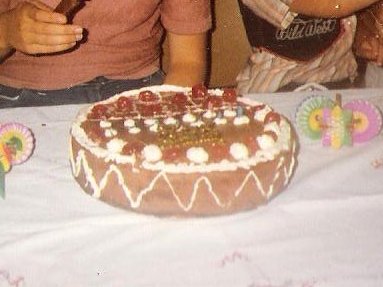

At the end of the meal, as is customary in tavernas all over Greece, a dessert, compliments of the chef, is brought to your table when you ask for the bill. It consisted of two layers: a dark one on the bottom and a yellow one on the top. I immediately recognised that cake. It was the cake my mother made for my birthday (every single year - it never changed). One look at that cake, and I knew I was going to eat a semolina-based walnut (dark layer) and almond cake (light layer). My hunch was right, verified from the taste of the first bite - it was undoubtedly the cake my mother made in our house, the only difference being that my mother used to fill it with custard and top it with fresh cream for extra effect.

"The last time I ate this kind of cake was twenty years ago in my New Zealand home," I explained excitedly to the taverna owner when she next came round to our table. "My mother always made it for birthdays, Christmas parties and other special occasions. But she always used to finish it with cream to make it look more festive."

"Oh, that's a tourta (torte) your mother made, not a plain cake like this one." The woman understood exactly what kind of cake I was talking about. "When we make just the cake, we call it karidopasta if we add walnuts to it, and amigdalopasta if we add almonds. Βut when we fill it with cream, we call it tourta."

And there, in Evritania, the pieces of my past all came together for me. I was beginning to understand how my mother came to make this cake. It wasn't a cake she had learnt to make in her homeland, which explains why I rarely see it made in Hania. The Greek zaharoplasteia sell pasta, which vaguely resembles the tourta version, but these pasta cakes (pas-tes in the plural) come nowhere close to the taste of a tourta (possibly the progenitor of the modern Greek pasta): the former contain more (fake) cream, while the latter contain more cake than cream. Karidopasta (and amigdalopasta) are a local specialty of Evritania, which neighbours Aitoloakarnania (both regions are filled with streams and rivers, where nut trees abound), where many of my mother's Greek-NZ friends came from.

"Oh, I can't give you my recipe, dear," the taverna owner told me when I asked for it. "I make a huge tin for the taverna, so I use about 40 to 45 eggs! In your kitchen, you can make a version with just a dozen or so eggs, even half a dozen, if you want to make a small one just to try out the recipe and see what works for you. For each egg, you need a tablespoon of ground nuts, a tablespoon of sugar and a tablespoon of semolina."

"What about butter?" I asked. I thought that possibly she had forgotten to mention it.

"No, no butter, this cake has no fat. Just remember the one-of-each ingredient list, that's all, it's so simple. You can add some flavour to it with some cognac or vanilla, and a teaspoon of baking powder to make it rise. Oh, don't forget to grease your baking tray with some butter and sprinkle a little flour over it, so that your cake batter doesn't stick to the tin."

It doesn't surprise me that this cake does not use any fat. The region is covered in mountains, and it freezes in the winter. Butter may have been made in small quantities, but it would mainly have been used as a cooking fat. Forget about growing olives here - they dont like snow...

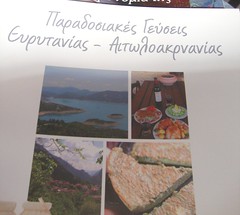

Having no notebook on hand (throughout my blog writing, I never use a notebook, relying only on my camera shots), I felt a little overwhelmed and wasn't quite sure if I would remember the recipe well enough to make it at home. To take the guesswork out of my kitchen experiments, I was lucky to come across the recipe in a book published by Δίρκη (Dirce), the Network of Tourist Enterprises in Evritania and Aitoloakarnania, which included the recipe for this very cake that we tried in Evritania. Interestingly, the name 'Dirce' was chosen for this network, as symbolic of the cooperation of the local enterprises, given that Dirce (in ancient Greek mythology, the daughter of Acheloos - the name of the river running through Evritania - and sister of Peirene) was the name of one of the two ferry boats (the other was named Peirene) which used to transport passengers and vehicles in the 1970s between Evritania and Aitoloakarnania over Kremasta Lake. This form of transport does not exist today since bridges connect the two regions by road - Tatarnas and Episkopi.

Having no notebook on hand (throughout my blog writing, I never use a notebook, relying only on my camera shots), I felt a little overwhelmed and wasn't quite sure if I would remember the recipe well enough to make it at home. To take the guesswork out of my kitchen experiments, I was lucky to come across the recipe in a book published by Δίρκη (Dirce), the Network of Tourist Enterprises in Evritania and Aitoloakarnania, which included the recipe for this very cake that we tried in Evritania. Interestingly, the name 'Dirce' was chosen for this network, as symbolic of the cooperation of the local enterprises, given that Dirce (in ancient Greek mythology, the daughter of Acheloos - the name of the river running through Evritania - and sister of Peirene) was the name of one of the two ferry boats (the other was named Peirene) which used to transport passengers and vehicles in the 1970s between Evritania and Aitoloakarnania over Kremasta Lake. This form of transport does not exist today since bridges connect the two regions by road - Tatarnas and Episkopi.I'm presenting the original recipe, as found on the web and in the cookbook. Variations of this cake are found below the recipe.

For the cake batter, you need:

12 eggs, separated

12 tablespoons of roughly chopped walnuts (or almonds)

12 tablespoons of large-grain semolina (fine-grain if using almonds instead of walnuts)

12 tablespoons of sugar

1 teaspoon each of ground clove and cinammon (I didn't use these flavourings - I don't recall them in my mum's cakes, so I omitted them from here too)

1 teaspoon of baking powder, dissolved in half a glass of cognac

grated orange zest

1 vial of vanilla

3 glasses of sugar

2 glasses of water

a slice of lemon

a cinammon stick (which again I omitted)

Whisk the egg yolks with the sugar; beat well, preferably with an electric mixer. Add the walnuts, cloves, vanilla, cinnamon and cognac, and mix well. Now add the semolina spoon by spoon, and mix well. Whisk the egg whites in a separate bowl. Add them to the yolk mixture, but beat them in lightly, just enough so that everything is mixed evenly. Pour the mixture in a large greased and floured baking tin. (I took no chances here; I remember my mother using baking paper!) Bake in a moderate oven at 200C until the top of the cake is golden and has formed a firm crust (approximately 35-40 minutes).

For a more impressive effect, make both varieties of the cake (like the taverna owner), halving the provided recipes to make each one. Pour the walnut batter into the baking tin, and cook for 10 minutes, so that the cake simply forms a crust on the top. Then pour in the almond batter and cook until the cake is done (approximately 30-40 minutes longer).

The same cake can be made into a torte: When the cake is cool, take it out of the tin by shaking it upside down onto a large platter. Slice through the cake in the middle (my mother used to have me help her to cut the cake into three - not just two! - slices). Lay each slice on a separate platter and pour syrup over each one, one spoonful at a time, making sure you cover each slice without making them overly soggy. At this stage, it doesn't matter if the cake slices break (it will be covered with cream and no one will be able to see the breaks). And for a more spectacular effect, just make two different cakes: one with almonds and one with walnuts - the former is a yellow cake, while the latter is brown.

Make a custard filling, enough to put the slices back together again, one on top of the other. (You can use both vanilla and chocolate fillings for each slice if you slice the cake into three layers to make an impressive display of your culinary prowess.) Whip some fresh cream and cover the top and sides of the cake. The cake can then be decorated with more cream (again, my mother would frost the cake with chocolate whipped cream and decorate it with vanilla cream), adding cherries and chocolate snow if desired.

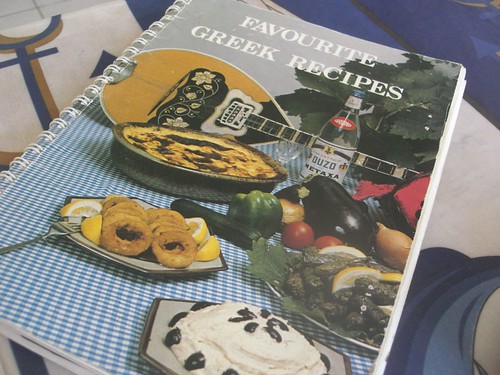

The cake is simple to make - the assembly requires a bit more attention than what I usually pay to cake-making, but it really isn't a complex recipe. This makes one of the best birthday cakes ever, and will be remembered by your children for the rest of their lives. I'm very lucky to have discovered this cake at this moment in my life when I have young children myself, especially since they never had the chance to taste their grandmother's baking. Although I've looked through my mother's cooking journal, I found some of her notes difficult to follow: she usually jotted the ingredients and left out the method. I've looked through my first-edition copy of Favorite Greek Recipes, produced by the Greek Community of Wellington, and found similar no-fat cake recipes, using almonds or walnuts, assembled as tourta, but none use semolina. If anyone has a Greek-NZ tourta recipe to share like this one, I'd love to hear from you.

The cake is simple to make - the assembly requires a bit more attention than what I usually pay to cake-making, but it really isn't a complex recipe. This makes one of the best birthday cakes ever, and will be remembered by your children for the rest of their lives. I'm very lucky to have discovered this cake at this moment in my life when I have young children myself, especially since they never had the chance to taste their grandmother's baking. Although I've looked through my mother's cooking journal, I found some of her notes difficult to follow: she usually jotted the ingredients and left out the method. I've looked through my first-edition copy of Favorite Greek Recipes, produced by the Greek Community of Wellington, and found similar no-fat cake recipes, using almonds or walnuts, assembled as tourta, but none use semolina. If anyone has a Greek-NZ tourta recipe to share like this one, I'd love to hear from you.Just imagine: if I hadn't been to Karpenisi on holiday this year, I would never have rediscovered this recipe!

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.