This post forms part of the series of our culinary adventures from our recent trip to Paris and London.

Education is a powerful tool. It is one of the most important factors in changing people's attitudes and behaviour. It is a positive force in the development of a nation, and it can even be used to instil prejudice and disseminate propaganda. I was the first person in my family to go to university; none of my ancestors had even completed primary school. To be educated in an English speaking country is both a blessing and a curse: on the one hand, English-speaking nations always had some of most respected educational systems, and high levels of education (

in the good old days, anyway); on the other hand, an English-language education is often monoculturally-inclined (at least, that's what mine was like), given the language's widespread use. If I had been raised in Greece and not New Zealand, my life would have been dramatically different now.

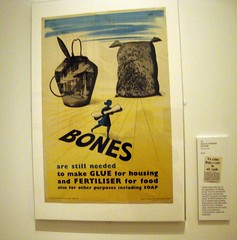

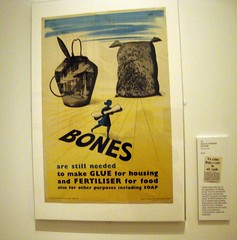

Forget what Gordon Ramsay told you about saving bones for stock making (Kitchen Front IWM cafe tray cover); in WW2, bones were needed for making glue and fertiliser (WW2 Ministry of Food campaign poster).

Forget what Gordon Ramsay told you about saving bones for stock making (Kitchen Front IWM cafe tray cover); in WW2, bones were needed for making glue and fertiliser (WW2 Ministry of Food campaign poster).

I was born nearly 20 years after the end of

food rationing in the UK, a system intended to restrict everyone's (including the royal family's

¹) consumption of basic food items in order for there to be a fair distribution of the limited resources

² available at the time, due to the destruction caused by WW2. I started school in 1970, and my teachers were likely to have been at least 25 years old or more; even though food rationing was not practiced in NZ, it's likely that NZ was heavily influenced by such an event, since NZ still had a strongly British influence, and her most important trading partner was in fact Britain. Some of my teachers were actually born in the UK (

a net exporter of population to Australia, South Africa and NZ in the 70s and 80s).

The sinews of war - the importance of the colonies: "In the desperate austerity of the 1940s, the colonies were seen less as fragile possessions to be held in trust than as economic assets to be milked for all they were worth. Administrators who had spent most of their careers cautiously guarding the equilibrium of their colonies now devoted their energies to cash crops, marketing boards, monopolies, rationing and 'Grow More Food' campaigns." (Dominic Sandbrook, Never Had It So Good, 2005)

The sinews of war - the importance of the colonies: "In the desperate austerity of the 1940s, the colonies were seen less as fragile possessions to be held in trust than as economic assets to be milked for all they were worth. Administrators who had spent most of their careers cautiously guarding the equilibrium of their colonies now devoted their energies to cash crops, marketing boards, monopolies, rationing and 'Grow More Food' campaigns." (Dominic Sandbrook, Never Had It So Good, 2005)

As a kiwi schoolchild, it never occurred to me that what my teachers were teaching me in Social Studies and what my Domestic Science teachers were teaching me during the cooking classes in manual training, were all partly based on British WW2 experiences. I thought it was simply the outcome of their own high level of education, not the effects of WW2, a concept which conjured up images of Europe and communism, bombed out buildings and Hitler, none of which had much to do with the rolling green pastures dotted with white woolly sheep in the kiwi countryside and the plentiful supplies of cheap New Zealand lamb, creamy yellow butter and frothy full-fat milk. Even my parents thought of their new home as the land of 'του πουλιού το γάλα'

³.

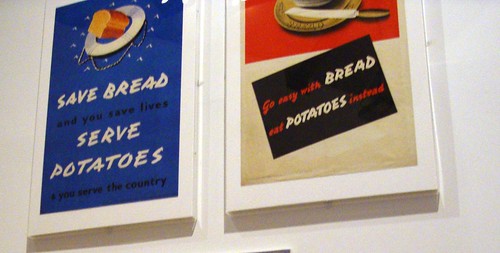

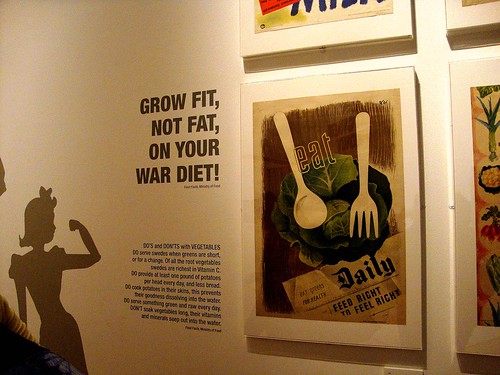

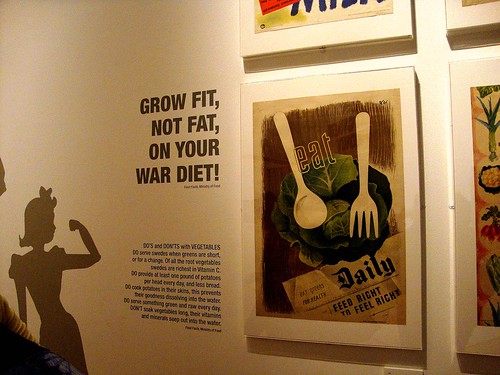

In WW2, vegetables suddenly came into fashion, and have been ever since - but you can't live off those alone: "No one carried a pound of superfluous flesh, in spite of the vast quantities of starchy food. They expended every ounce they ate in work... Vegetables and fruit were eaten because they were good for you, but it was the bread, potatoes, meat and floury puddings which staved off exhaustion." (Colleen McCullough, The Thorn Birds, 1977)

In WW2, vegetables suddenly came into fashion, and have been ever since - but you can't live off those alone: "No one carried a pound of superfluous flesh, in spite of the vast quantities of starchy food. They expended every ounce they ate in work... Vegetables and fruit were eaten because they were good for you, but it was the bread, potatoes, meat and floury puddings which staved off exhaustion." (Colleen McCullough, The Thorn Birds, 1977)

Tthe

Ministry of Food exhibition at the

Imperial War Museum in London was a

deja vu experience for me; I discovered my educational roots. The

Ministry of Food exhibition hows how the British public were re-educated to change the way they thought about food in post-WW2 Britain. This had long-lasting effects, and not just in the UK alone; the WW2 Ministry of Food's campaign influenced the farthest outposts of British colonialism.

Visiting the exhibition helped me to piece together the jigsaw puzzle of my own personal food history. For instance, why did I scold my mother when she cooked a potato dish and served bread with it?

Why did I insist (in those days) that brown bread was healthier than white bread?

Brown bread - you either loved it or hated it, as the quotes attest.

Brown bread - you either loved it or hated it, as the quotes attest.

Why did she show disgust when I bit into my apple with the skin on, or boiled potatoes without peeling them?

WW2 food Dos and Don'ts: an image of my schoolteachers immediately came to my mind as I was reading these, and I didn't even go to school in the UK.

WW2 food Dos and Don'ts: an image of my schoolteachers immediately came to my mind as I was reading these, and I didn't even go to school in the UK.

Why am I trying to force-feed my husband par-boiled vegetables?

It's hardly a European habit to eat crunchy raw vegetables, nor is it deemed suitable to leave them all unpeeled. So where did I pick up my non-European ways, given that I was born European (well, that's how the NZ census used to classify me).

Do carrots really make your eyesight better? And why do I keep the adage "meat and two veg" in mind whenever and with whatever I'm cooking?

The answer to all of these questions lies in the UK's post-WW2 educational campaign to make better use of scarce resources, now almost a thing of the past in the lands of plenty that the Western world has become, the high level of literacy and education needed to teach old dogs new tricks, and Britain's readiness -

having already been through similar problems arising during WW1 - to introduce the food rationing system efficiently and effectively

ª.

*** *** ***

The consequences of WW2 destroyed the food chain throughout the whole of Europe. Some countries, like

Greece, had lost all the infrastructure needed to distribute food to all the population, hence many people starved. Being essentially an island, Britain was cut off from her crucial food supplies by the sinking of her ships. Due to a lack of food during and after WW2, food rationing was in force in Britain from 1940 until 1954. In order to obtain basic food supplies, everyone had to have a ration book which they had to use at the grocer's that they were registered with; they could only purchase food items (including clothing and tools) with their ration book, and only in the amounts that they were legally entitled to. Children, pregnant women and labourers were given extra rations. Even vegetarians were catered for and given extra egg and cheese rations.

The photo shows a week's worth of food rations, as well as the Queen's ration book.

The photo shows a week's worth of food rations, as well as the Queen's ration book.

The government created the

Ministry of Food (hence the name of the IWM exhibition), which served to fairly distribute all the food in the country (both local produce and imported products) to all the people in Britain. It also had another more important task: to re-educate the import-dependent British people to produce their own food (and therefore reduce imports), eat seasonally, recycle and not waste. It all sounds familiar, doesn't it? Except that in those days, there were no supermarkets or refrigerators.

UK food imports: the most carbon footprint laden are tea, sugar and rice, each one needing up to 11,200 miles of travel to get to the UK: "... lamb and butter from New Zealand, tea from India, chocolate from Nigeria, coffee from Kenya, and apples, pears and grapes from Africa... [and] toys that were identified as 'Empire Made'." (David Cannadine, Ornamentalism, 2001)

After WW2, the food situation actually worsened rather than improved, since the US stopped sending food supplies to Britain. Soldiers came home, families grew; there were more mouths to feed:

Britain in 1945... Meat rationed, butter rationed, lard rationed, margarine rationed, sugar rationed, tea rationed, cheese rationed, jam rationed, eggs rationed, sweets rationed, soap rationed, clothes rationed. Make do and mend." (David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 2007)

Without limitations on the amount for each individual and an emphasis on the importance of maintaining a vegetable garden, Britain would have found it very difficult to feed her people. A fortnight after the end of WW2, the government made it clear to the people that "Every inch of useable English soil will still have to be made to grow food" (David Kynaston,

Austerity Britain, 2007).

Allotments were made use to the full during and after WW2. I can feel the pain of the owners of these ones (left: from the DLR to Lewisham (Mudchute??); right: from the train to Gatwick): when you don't live near your patch of land, it is difficult to tend it. The colour of the sky also dampens your mood (pun not intended). They remind me of our orange orchards and olive groves, 10km away from our house - our summer garden is a different story altogether.

Allotments were made use to the full during and after WW2. I can feel the pain of the owners of these ones (left: from the DLR to Lewisham (Mudchute??); right: from the train to Gatwick): when you don't live near your patch of land, it is difficult to tend it. The colour of the sky also dampens your mood (pun not intended). They remind me of our orange orchards and olive groves, 10km away from our house - our summer garden is a different story altogether.

A high reliance on food imports is now viewed as highly unsustainable due to the carbon footprint-laden food miles; the idea of a poor country providing food for a rich country is also contentious. It seems incredible that 70 years ago, a country as advanced as Britain was able to provide only a third of the food required to feed its own population (around 46 million at the time), relying heavily on food imports, whose transport to the UK required long sea journeys from the colonies.

We all think and talk about food eternally, not because we are hungry but because our meals are boring and expensive and difficult to come by... what I wouldn't give for orange juice or steak and onions or chocolate or apples or cream. (1941 diary extract, quote from the Ministry of Food exhibition)

Throughout Britain's history, food was always imported to keep people fed;

food imports have been a crucial element of Britain's food supply since the industrial revolution. From the colonies, Britain acquired a liking for exotic tastes that local food could not provide, especially for what has often been termed as the Brits' 'insatiable desire for something sweet': the ease of importing novel (and tasty) food into Britain created a certain dependence on them, as in the cases of tea and sugar.

The exhibits in the photos above were the most nostalgic for me. They reminded me of the plain-looking (but tasty) cakes and biscuits we ate during a morning or afternoon break in tea-houses (aka cafes) when I lived in Wellington in the 1980s. They represent a period in time that we cannot return to, before lattes and cappuccinos.

The exhibits in the photos above were the most nostalgic for me. They reminded me of the plain-looking (but tasty) cakes and biscuits we ate during a morning or afternoon break in tea-houses (aka cafes) when I lived in Wellington in the 1980s. They represent a period in time that we cannot return to, before lattes and cappuccinos., and it isn't only in the past

that food was being used as a weapon. With fewer imports now available, the daily British diet was radically changed with the introduction of food rationing. All of a sudden, milk and eggs were replaced by their powdered substitutes; fresh eggs were limited to one a week and fresh milk was allocated to those who needed it most (mainly children). Since people had never used these powders to cook with before, they had to be 'taught' to use them appropriately, which is where the powerful role of education and literacy came into play, via pamphlets, radio broadcasts, demonstrations, newspaper advertisements and posters, all of which were prepared by the Ministry of Food.

Fish wasn't rationed, but fresh fish was hard to find. Salt cod was a relatively new product for the British; people were, once again, 'taught' to use it.

Complaining about the tastelessness of egg powder did no good when there was no alternative. Even the weekly allowance of one fresh egg per week wasn't always easy to get hold of, for example, when there was a strike; not everyone was happy about the political and economic situation at the time, even if the war was over. All meat (except chicken) was strictly rationed. Fish wasn't, but it was expensive and hard to come by. Canned goods were also allocated by rationing. Fresh fruit and vegetables were eaten by those who had an allotment or used their garden to grow them; otherwise, people had to queue up to buy them when they were available. Bread and sweets were also rationed on and off. Everyone ate the same food, cooked in the same way, for nine years.

Meat ration lasts for only three evening meals, ... that is Saturday, Sunday, Monday. Tuesday and Wednesday I cook a handful of rice, dodged up in some way with curry or cheese. But the cheese ration is so small there is little left. Thursday I have a pound of sausages. These make do for Thursday, Friday and part of Saturday... All rather monotonous, but we are not hungry... (diary extract, quote from the Ministry of Food exhibition)

The end of the war only made the rationing situation worse, when the US stopped supplying food to the UK: "

there are bad times just round the corner," a politician of the time warned. Food rationing has been blamed for the decline in British cuisine and people's interest in cooking. The above account gives a grim view of the food situation. People could not really enjoy their food; they ate to sustain themselves.

At the risk of sounding ignorant, I have not the foggiest idea of what is being pictured here (can Jamie Oliver?), and neither does it look particularly appetising. Was food rationing to blame for the lack of attraction to/in the British cuisine, or was it simply a result of Britain's main interests lying away from the land, home and hearth, so that most people were occupied with other business and not with food? Well, I guess we can definitely say, by looking at these photos, that British cuisine has no influence whatsoever in Greek cuisine...

At the risk of sounding ignorant, I have not the foggiest idea of what is being pictured here (can Jamie Oliver?), and neither does it look particularly appetising. Was food rationing to blame for the lack of attraction to/in the British cuisine, or was it simply a result of Britain's main interests lying away from the land, home and hearth, so that most people were occupied with other business and not with food? Well, I guess we can definitely say, by looking at these photos, that British cuisine has no influence whatsoever in Greek cuisine...

In amongst the misery, there are also many positive aspects of the WW2 food rationing system. It helped people to develop the qualities of living in a fair world where everyone patiently waited until it was their turn for something, so that no one couldn't say they were given an equal chance to survive:

The British prided themselves on their ability to form an orderly queue; they had plenty of opportunities to prove it. (Dominic Sandbrook, Never Had It So Good, 2005).

We did think that once Japan was beaten, we should do away with queues, but it doesn't seem like it. Yesterday, I queued 1/2 an hour in Woolworths for some biscuits... The fish problem seems to be a bit better here - it isn't quite so rotten, although the queues are still there (Muriel Bowmer, In: David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 2007).

Queuing - ie, waiting for your turn when it came up - is what I remember most about the years I spent living in New Zealand, everyone's right to a fair share of everything, their rightful share of the pie, a concept that was pretty much shattered for me when I first came to live in Greece in 1991

º, where some people seemed to be getting a huge hunk of it, while others never even saw it.

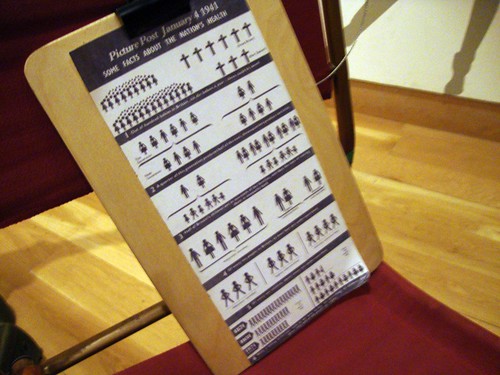

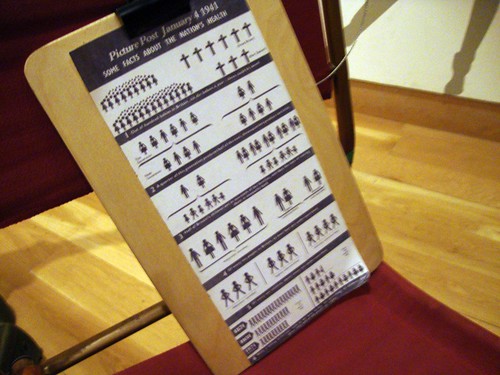

The nation's health: the NHS was established in 1948 during the rationing period:

"During the war, although there were privations and shortages, people generally had a good diet. When the war ended, it was found that the average food intake was much higher than when it began... with virtually no unemployment and the rationing system, with its fixed prices, [poor people] ate better than in the past... People at all levels of society took nutrition seriously and ate sensibly with the rations and whatever vegetables and fruit were available, and with less sugar and fewer sweet snacks there was less tooth decay. As a whole, the population was slimmer and healthier than it is today; people ate less fat and sugar, less meat and many more vegetables." (Jill Norman, Eating for Victory, 2007)

The nation's health: the NHS was established in 1948 during the rationing period:

"During the war, although there were privations and shortages, people generally had a good diet. When the war ended, it was found that the average food intake was much higher than when it began... with virtually no unemployment and the rationing system, with its fixed prices, [poor people] ate better than in the past... People at all levels of society took nutrition seriously and ate sensibly with the rations and whatever vegetables and fruit were available, and with less sugar and fewer sweet snacks there was less tooth decay. As a whole, the population was slimmer and healthier than it is today; people ate less fat and sugar, less meat and many more vegetables." (Jill Norman, Eating for Victory, 2007)

But all that talk of vegetables being good for you, digging for victory by growing your own, recycling to reduce imports, is all by the by; this propaganda served its purpose (to make you feel guilty, just like the carbon footprints ideology in today's society), but was

readily forgotten once the good times came back.

Rationing's success lay in its effort to maintain the whole nation's health with everyone getting the due attention they needed. Obesity and tooth decay were practically unheard of, everyone had access to food and no one starved; everyone's voice was heard, from the baby to the pensioner, and everyone was taken into account, from the vegetarian to the cats and dogs.

*** *** ***

Rationing finally came to an end almost a decade after the war was over.

'Almost at once,' wrote Harry Hopkins, 'affluence came hurrying on the heels of penury. Suddenly, the shops were piled high with all sorts of goods. Boom was in the air.' (Dominic Sandbrook, Never Had It So Good, 2005).

It has been suggested that rationing could be re-introduced in modern times, for the purposes of living in a more environmentally-friendly world:

"I'm afraid you've reached your monthly allowance of Kenyan green beans, Sir - you'll have to buy locally grown ones from now on. The last truckload we saw of those came in last week..."

... or perhaps as a way to curb obesity:

"Sorry, Ma'am, I see you've been classified under the Big O category - I'm afraid you've used all your bacon rations for this month, so you can only buy low-fat turkey meat for the next fortnight!"

... or even just to maintain the community spirit: To promote the idea of people registering with a local food supplier, they might be given incentives such as fixed prices, discounts, and the like, for similar reasons as when you have a neighbourhood butcher or grocer where you do your regular shopping, in order to give small businesses a better chance to survive and to provide a kind of 'neighbourhood watch' service:

"'Ello there, Mrs Patel, sorry to 'ear about your 'usband. Was a good man, weren't 'e? Well, I see your sons' been taking good care o' you. The older one popped in yesterday, axed me if I'd 'ad your OAP milk rations sent to you, an' I told 'im I did. Good lad, 'in 'e?"

In the

market-driven economy that we all live in, it sounds highly unlikely that it would be accepted by most...

But it

did work in WW2 Britain, and I cannot help but look upon the food rationing system in great awe, when I know that no one starved in a country that could not even feed her own people,

as they did elsewhere. They patiently waited for their turn to pick up their weekly rations, and never forgot to say their good mornings, pleases and thank yous (as they still do), and always remembered to queue, whether it was raining or the sirens had just gone off warning of an air raid, or a V2 rocket had just landed and shaken the ground beneath their feet, the food queues always being the last to disperse.

Moving photos adorn the walls of the exhibition: the milkman carrying a crate of full bottles of milk, walking amongst the rubble of a bombed London suburb; a mother of 16 children, looking at all the ration books of her family members, working out her food needs for the week; the queue of people at a bombed fishmonger's premises. There are lessons to be learnt from the food rationing system in the modern world amongst

the beleaguered nations in the present economic crisis: to weather the storm, it is not enough to take measures, one must also wait their turn. If only things could have been like this for the Greek people during WW2. Sadly, despite the food-rich world that they lived in,

many Greeks died of hunger during WW2. We can't change the past, we can only learn from it.

¹People noticed that the royal family's faces always looked rosier than the rest of the population's: "... Mary King managed to get near to the car of the visiting King and Queen: 'She looked a little too matronly for her age. Considering the rationing... she certainly looked well-fed.' " (David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 2007)

²The black market was thriving for those who had the means (ie money) and the right connections: "... the black market... - including off-ration and under-the-counter sales as well as tipping and favouritism - were at least as extensive after the war as during it; ... I suspect there's more dishonesty in this country today than for many years." (David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 2007)

³Bird's milk, in the literal sense; metaphorically, this phrase is used to denote 'abundance'.

ªBritain had learnt some hard lessons during WW1, when food supplies were so depleted that there were only 6 weeks' worth of food in country - the situation bears a great similarity to Greece's recent money woes: most of the time, there is only 6 weeks' worth of money left in the state coffers to pay out pensions and salaries...

ºThings are better now in Greece, but they weren't perfect in WW2 Britain either: "I doubt if a single Englishman did not avail himself of the help of the black market." (Diary extract, In: David Kynaston, Austerity Britain, 2007). Everyone will grab a chance when offered it, won't they?

*** *** ***

I rounded off my visit to the exhibition with a meal from the

Kitchen Front - the

museum cafe (coincidentally voted by

radio listeners in 2008 as one of the best museum cafes in London) had been given a facelift to coincide with the Ministry of Food exhibition, selling WW2-inspired foods.

I had the baked potato with kipper stuffing. Potatoes are easy to grow and store in the UK, and were promoted as a 'protective food'. Fresh fish wasn't on the ration, while lettuce (but without the vinaigrette, of course!) could be grown in the garden or even above the bomb shelter by the tenant/owner of a house, so this meal could be said to be very ration-friendly. Very good indeed; possibly boring on an everyday basis (the main problem with Britain's WW2 rations), but tasty. I also fancied a slice of that

beetroot cocoa cake on offer, mainly to compare my muffin version with the cafe's, but passed on it, since I had to keep plenty of extra space in my stomach for... (

the post on that is coming soon).

My chocolate beetroot muffins - a good way of incorporating fresh vegetables in sweets and cutting down on ingredients that were difficult to access during the war.

If I had to mention a minus point about the exhibition, I'd say it was the amount of white spaces on the wall; I would have liked them to be covered with more quotes and newspaper clippings. The

Imperial War Museum offers entertainment and knowledge for all ages and interests - we've visited the museum three times already as a family! Look at how my own family was entertained while I went to see

Ministry of Food exhibition:

(The Terrible Trenches - thanks to lego for the photo - is a specially designed children's exhibition; the WW2 weapons on the table were laid out for Mr OC's enjoyment - thanks to Paul Cornish at IWM)

We were also greatly amused when the young man at the welcome desk of the museum, after patiently listening to me as I explained in English which tickets we wanted to buy for which exhibitions, replied to us in Greek; we can be found all over the place, can't we!

And special thanks to Cynthia, who provided the motivation for my whole trip.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.