Greeks like to tell you that high school is 'difficult'; isn't high school 'difficult' anywhere in the world, especially when you compare high school to primary school? I don't like to stress myself out about higher education, but recently I noticed that my son looked very stressed out with his homework. I really hate helping my kids with homework, because most of the time, it is akin to actually doing the homework for them. That has serious repercussions in the long run, which are widely discussed in educational sites all over the world. But I don't mind nudging them in the right direction, as long as this means that I am helping them to learn skills that they can transfer to other problem-solving situations.

We all have a lot to read these days because we use the internet, which basically means we need to sift through a lot of information. But we don't read everything on a web page, we just look for the information we want/need. We all have different ways to do this. First and most important for me is to look at a web page in the same way that I view a picture, or a photo. Second, I look for the key words on the page. To do this, I run my eyes over the text and ignore everything that looks unimportant. Thirdly, I use all the graphics that are available on the page: this includes capitalised words (which therefore are names) and numbers (which could be quantities or dates). Fourthly, if I'm not sure what's important, I read the first sentence of the first and last paragraph, OR I read 1-2 words on each line, my eyes jumping from one line to the other in the text. There are other ways to do this too, eg the zig-zag method. Whatever way you speed-read is a personal choice - as long as it works for you. And the most important thing is - see First above: a page is a picture.

We all have a lot to read these days because we use the internet, which basically means we need to sift through a lot of information. But we don't read everything on a web page, we just look for the information we want/need. We all have different ways to do this. First and most important for me is to look at a web page in the same way that I view a picture, or a photo. Second, I look for the key words on the page. To do this, I run my eyes over the text and ignore everything that looks unimportant. Thirdly, I use all the graphics that are available on the page: this includes capitalised words (which therefore are names) and numbers (which could be quantities or dates). Fourthly, if I'm not sure what's important, I read the first sentence of the first and last paragraph, OR I read 1-2 words on each line, my eyes jumping from one line to the other in the text. There are other ways to do this too, eg the zig-zag method. Whatever way you speed-read is a personal choice - as long as it works for you. And the most important thing is - see First above: a page is a picture.

Another point that doesn't seem to be well-used in high school is personal experience. High school focusses on bookish learning so it's very academic. Some children are not academic, but quite a few of those non-academic ones would benefit if they were taught to use their personal experiences in the book-learning methods. Here is an example: So here we are in Crete, and the subject of the test is Minoan civilisation, focussing on the ανάκτορα, the palace, the most famous being in Knossos, 150 kilometres away from our house. Despite having been to Knossos with my kids on a memorable school trip, I still found my son just reading his texts to gain the knowledge he thought he needed. Somewhere along the line, the real life connections to Knossos were lost and proper application was not made of past experiences where new knowledge was acquired.

Another point that doesn't seem to be well-used in high school is personal experience. High school focusses on bookish learning so it's very academic. Some children are not academic, but quite a few of those non-academic ones would benefit if they were taught to use their personal experiences in the book-learning methods. Here is an example: So here we are in Crete, and the subject of the test is Minoan civilisation, focussing on the ανάκτορα, the palace, the most famous being in Knossos, 150 kilometres away from our house. Despite having been to Knossos with my kids on a memorable school trip, I still found my son just reading his texts to gain the knowledge he thought he needed. Somewhere along the line, the real life connections to Knossos were lost and proper application was not made of past experiences where new knowledge was acquired.

There are a whole host of problems involved here: the teacher, the child, the parent, television, information overload and junk food are all involved. The biggest issue is probably having an awareness of the problems involved. There was so much less to read when I was my son's age, and fewer resources to tap into. We now need to know what not to read...

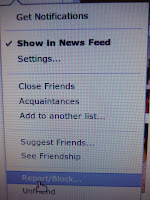

Two months after terms started (don't forget that we were plagued with strike action), my son seemed to be having problems with his biology homework; he asked me to help him with a crossword (see below) based on biology terms. I have enough problems doing this in English, and I knew I would not be able to help him in Greek. But I also knew that all the answers to the questions are contained in the texts the kids are expected to read, so I told him to look at the texts more carefully before attempting the exercise page.

|

| Click to enlarge |

"But I've already read it, and I can't find the answers," he said. I decided this was impossible, but I had to confirm it in some way myself. So I checked the texts, which I found not so difficult to read after all, even for my own level of Greek, and there were lots of graphics to accompany them, which illustrated many of the points in the text. This all made sense to me, and I finally understood my son's problems: he had not understood how to use the text together with the graphics in order to grasp the meaning of the text he was studying. I also realised that he seemed not to have been taught 'how' to read something for understanding. He wasn't underlining words that looked important: instead, he underlined whole paragraphs; he wasn't using arrows to point the graphics to the text where it explains them: he was reading the text separately from the pictures. It's difficult to know whose job it is to teach kids skills about how to be better readers - the biology teacher may see this as the literature teacher's job, while the literature teacher may be teaching skills for reading 'story' texts. Both teachers may actually have said a word or two to the kids already about this - but when you are starting high school, and it all seems new to you, you may not have paid enough attention to what your teacher was saying. Perhaps also... no one has said anything about reading skills...

Whatever the case, I found I could easily do the exercise just by reading the text quickly and picking up the key words, which were already in the exercise; some were even in bold text. I also used basic crossword skills to eliminate wrong choices, eg the number of letters in a word, and possible adjacent letters in Greek spelling. I admonished my son for his laziness - he could have done all this himself. But if he hasn't been taught to do it in the first place...? I suddenly remembered that at that very moment that I was teaching him to read for information, I had been doing a similar lesson in my English classes with... graduate science students.

We all have a lot to read these days because we use the internet, which basically means we need to sift through a lot of information. But we don't read everything on a web page, we just look for the information we want/need. We all have different ways to do this. First and most important for me is to look at a web page in the same way that I view a picture, or a photo. Second, I look for the key words on the page. To do this, I run my eyes over the text and ignore everything that looks unimportant. Thirdly, I use all the graphics that are available on the page: this includes capitalised words (which therefore are names) and numbers (which could be quantities or dates). Fourthly, if I'm not sure what's important, I read the first sentence of the first and last paragraph, OR I read 1-2 words on each line, my eyes jumping from one line to the other in the text. There are other ways to do this too, eg the zig-zag method. Whatever way you speed-read is a personal choice - as long as it works for you. And the most important thing is - see First above: a page is a picture.

We all have a lot to read these days because we use the internet, which basically means we need to sift through a lot of information. But we don't read everything on a web page, we just look for the information we want/need. We all have different ways to do this. First and most important for me is to look at a web page in the same way that I view a picture, or a photo. Second, I look for the key words on the page. To do this, I run my eyes over the text and ignore everything that looks unimportant. Thirdly, I use all the graphics that are available on the page: this includes capitalised words (which therefore are names) and numbers (which could be quantities or dates). Fourthly, if I'm not sure what's important, I read the first sentence of the first and last paragraph, OR I read 1-2 words on each line, my eyes jumping from one line to the other in the text. There are other ways to do this too, eg the zig-zag method. Whatever way you speed-read is a personal choice - as long as it works for you. And the most important thing is - see First above: a page is a picture.

The Greek school system is notorious for using the parrot-learning technique. But I can now understand why this happens: kids aren't being taught to read properly (OR, they are not paying attention to teachers when they are being taught to do so). So, they parrot-learn. I found this going on when my son asked me to check his knowledge of ancient civilisations before he would be tested on it. (Gawd, I really hate doing this - but look at how insecure he is feeling, that he actually asks me to do it.) For this lesson, we had fewer graphics and more texts on the page. When I asked him a question based on the texts he was learning, I noticed he was hesitating before answering, because... he was remembering not the information, but the order of the words that he had read. Another thing I noticed was that when he actually answered my question correctly, it would not only be in the exact words he had read in the book... but he kept reciting the entire paragraph, not knowing when to stop providing information, which would have been the answer to a later question! Again, he had not highlighted key words: he had highlighted whole paragraphs, "because the teacher told us this paragraph was important, and the next one wasn't"... Again, he wasn't using a technique to help him remember information - he was just memorising for short-term use, instead of learning for long-term use.

Another point that doesn't seem to be well-used in high school is personal experience. High school focusses on bookish learning so it's very academic. Some children are not academic, but quite a few of those non-academic ones would benefit if they were taught to use their personal experiences in the book-learning methods. Here is an example: So here we are in Crete, and the subject of the test is Minoan civilisation, focussing on the ανάκτορα, the palace, the most famous being in Knossos, 150 kilometres away from our house. Despite having been to Knossos with my kids on a memorable school trip, I still found my son just reading his texts to gain the knowledge he thought he needed. Somewhere along the line, the real life connections to Knossos were lost and proper application was not made of past experiences where new knowledge was acquired.

Another point that doesn't seem to be well-used in high school is personal experience. High school focusses on bookish learning so it's very academic. Some children are not academic, but quite a few of those non-academic ones would benefit if they were taught to use their personal experiences in the book-learning methods. Here is an example: So here we are in Crete, and the subject of the test is Minoan civilisation, focussing on the ανάκτορα, the palace, the most famous being in Knossos, 150 kilometres away from our house. Despite having been to Knossos with my kids on a memorable school trip, I still found my son just reading his texts to gain the knowledge he thought he needed. Somewhere along the line, the real life connections to Knossos were lost and proper application was not made of past experiences where new knowledge was acquired.There are a whole host of problems involved here: the teacher, the child, the parent, television, information overload and junk food are all involved. The biggest issue is probably having an awareness of the problems involved. There was so much less to read when I was my son's age, and fewer resources to tap into. We now need to know what not to read...

All Greek school text books are available online at http://dschool.edu.gr/.

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.