Tune in daily this week to see how we spent our family holiday in Central/Northern Greece.

Before visiting the artificially created Kremasta Lake, I had no knowledge about it whatsoever.

After a refreshing gazoza by the old romantic bridge of Arta, we set off on to our next destination: Karpenisi, a town set on the slopes of forested mountains in Central Greece. The weather was so hot you could bake bread under a tin roof. The stuffy air left us gasping; time to turn on the air conditioner of the trusty loyal family car, a battered 12-year-old Hyundai Accent, laden with suitcases. We were in for a bumpy ride through the largely unexplored countryside of Central Greece. Τhe route my friend had dictated to me was considered uncharted territory on my 20-year-old map, the one I was still using from the time I first arrived in Greece. We had been considering buying a GPS for a while now. Its purchase is still pending: we are waiting to buy the new car first.

My friend Hrisida sent me a text message explaining the route: "Arta - Komboti - Halkiopoulo - Tatarnas Bridge - Loggitsi - Krenti - Kerasohori - Karpenisi. You will find Lake Kremaston very impressive."

"There's no real arterial route from Arta to Karpenisi," Hrisida had warned me. "Μην βραδιαστείτε" was her main advice: don't let nightfall come. We stopped off at a petrol station to buy a new map. Good thing we did this early enough: petrol stations from Arta to Karpenisi are very hard to come by. Exiting Arta from the busy road by the impressive castle ruins leading out of the city, we remained chained to a line of traffic until we reached Sellades. Just after passing the Komboti junction, we left the modern world behind us. We were about to enter the depths of rural Greece, where the physical presence of humans had become a form of sport: human-spotting.

The densely forested damp mountains that we had travelled through in Epirus, with their low-lying clouds suspended among the hills and gushing rivers, even at this time of year (end of summer), suddenly gave way to the rocky mountains of Aitoloakarnania, some of them green and forested, others looking sunburnt from their barrenness. The road was winding interminably round hills that seemed to lead to nowhere. Villages were labelled on the map by name, but not necessarily signposted.

"Are you sure this is the right road?" my husband kept asking me. Yes, I felt sure this was the right road, since there seemed to be no other road to take. We looked out for the next sighting of houses. It never came early enough. The map said: "Katharovouni" but either we had blinked when we had passed the sign (or the houses) or it was simply not there. It was a case of either continuing to drive, or returning from the road we came from. We chose the former. The narrow roads did not make allowances for U-turns, being located dangerously either by a badly maintained ditch or at the outer edge of a precipice. We drove sometimes up, sometimes down, but always less than 50km/hour, often wondering if we were actually on the right road. We were in the middle of nowhere.

In that nowhere, we came across what looked like a newly-built kiosk, a wooden structure with seating arranged in a circle, with a tiled roof over it to block out the sun. Kiosks of this sort aren't rare in mountain country, but they are usually attached to a church, or maybe a housing settlement. In our case, there was nothing of the sort. It looked as though it was there to allow people to take in the panoramic sight of a series of mountains and hills backdropping against each other, each one fading into the horizon. No houses nearby, just the kiosk - and there was our first sighting of a human. "Always stop and ask for directions," Hrisida kept reminding me when she heard that I was planning this trip. We pulled over by the side of a steep cliff-hanging road. By now, we had stopped fearing for oncoming traffic; if that did actually happen, it would be a miracle in the outback country.

He looked quite young, no more than fifteen years old. He was sitting on the top of the back-supporting part of a bench talking into a mobile phone. What he was doing out here was none of our business. Presumably this spot had a good signal. It was also a good spot to get sunstroke just by staring up at the sky - the stark environment was blinding under the hot morning sun.

"Excuse me," my husband called out to the young man. "Can you tell me which is the next village?" my husband asked him. The boy stared at us, as if surprised to be interrupted. My husband repeated the question. The boy looked puzzled: he didn't know what the next village was.

"I'm from the Rahi", he explained to us. We looked for "Rahi" on the map, but there seemed to be no such place. The boy could not even place himself on the map when we asked him to show us where we were. He simply pointed towards an undefined direction in the air. No housing settlement was visible from where we were standing. My husband then tried another question tactic, a trick he had learnt over the years as a taxi driver: instead of asking the name of the next village, he asked him how long it would take to get to a village that was actually on the map:

"How far is Floriada from here?"

"Flo-what? Floyada?" The boy acted as though he had never heard of Floriada. His presence as a stranger to these parts of the remote mountain road felt sinister. We said goodbye to him, got back into the car and continued driving. A derelict house came into view after a few minutes of very slow driving round the bends, the ruins of a stone-built cottage. Then a little further on another one. And finally, what we were looking for: a faded signpost announcing 'Floriada", and then, a few well-kept properties whose shutters looked as though they had not been opened for quite some time. At least we knew we were on the right road.

Driving along empty Greek roads is not as perturbing as it sounds. It gives you time to stop and look at anything that takes your fancy. You can also take in the changes encountered on the journey. As we continued to wind up and down this remote part of the countryside, we came to understand what the words αγρότη and μοναξιά would mean in this area of Greece. Disused agricultural machinery and ancient vehicle models lined the unsignposted road, bordered by sometimes bare, sometimes forested hills and mountains on either side, with only a few houses, sometimes scattered on the hills, other times clustered in what looked to be a ghost town. It came as almost a shock when we saw a large party dining outside under the shade of a grapevine at one point. What were they doing here? Where did they work? What were they living off? Did the mailman pass by their house on a daily basis? The condition of the roads led me to believe that these people never left their homes for long, never went too far away from their houses. They were living as though they did not exist. If it weren't for the telephone, they would be forgotten.

We noted the change in the scenery as we drove on: just like the scenery, the weather also began to change. The bare mountainsides gave way to thick forests with fir trees, which blocked out the sun's rays, cooling down the air, and making driving conditions more bearable. I imagined the scene in winter: fir trees covered in snow, a perfect Christmas image. This change of scenery also signalled our entry into another prefecture: from Arta in Epirus, we crossed into Aitoloakarnania, and now we were heading towards Evritania. It is not difficult to understand why Greeks sometimes do not understand their compatriots spread across the country - the people change as the scenery changes. Every now and then, we would come across a few goats on the road. They would make the best climbers in these parts. The shepherds tending the flocks were nowhere in sight but occasionally we would come across a pick-up truck on the road.

On our way to Tatarnas Bridge, the sky became thick with clouds and showed signs of darkening. Even though it was only midday, I remembered Hrisida's words: "Μην βραδιαστείτε." But only the morning was almost over and it was nearing lunchtime. We were making our way to the artificially

created Lake Kremaston, considered a modern marvel when it first opened: at the time of its construction, it was the largest earth-filled hydroelectric project in Europe. In Greece, wherever there is a tourist attraction or site of interest,

there are tourist shops, cafes and tavernas. I was now looking forward to doing more human-spotting en masse. We did come across a few houses on the road, but most were tucked away amidst the greenery, off the main road, whose access was not easy to discern.

Eventually we came across what looked like a meeting spot. It didn't resemble a village square, but it seemed a perfect place to set up a small canteen van by the side of the road, next to a petrol station, for the occasional passersby to indulge in a bite to eat and a person to chat to. But how often did people pass this spot? It reminded me of another piece of advice that Hrisida had given me before the trip: "Δεν θα συναντήσεις ψυχή στο δρόμο"; 'you will not meet a soul on the road.' The whole time we had been on the road, we can't have seen more than ten cars. As this thought occurred to me, the pervasive silence of the area also began to infiltrate my mind. It was eerily quiet in these here parts. To add to the uncanniness of the situation, the whole time we were driving to our point of interest, it was sweltering. But as we began to draw closer to our destination, the wind began to rise, a few raindrops fell on the windscreen, and the sky lost its brightness.

The mountainsides were now mainly forested, giving a very fertile look to the area. Rock and boulder masses denoted the presence of streams and rivers, all leading to their final depository, Lake Kremaston; we were waiting for it to come into view, and we had now all become impatient. Where was that lake hiding?

The mountainsides were now mainly forested, giving a very fertile look to the area. Rock and boulder masses denoted the presence of streams and rivers, all leading to their final depository, Lake Kremaston; we were waiting for it to come into view, and we had now all become impatient. Where was that lake hiding?

I took out my cell phone to send a message to Hrisida. "Approaching Tatarnas," I typed, and clicked on the Send icon. The lake had still not come into view.

BIP! Message received, I thought. But I got a surprise when I looked at the screen. "Message not sent" had popped up on it. There was no signal. It was probably the only time I had no phone signal throughout our summer holiday. That's when fear overcomes you: no signal means you can't even ask for help if you get stuck in a ditch, or come across other trouble, like a wolf or boar straying out of the forest; I felt a sense of relief that it wasn't raining.

Driving on, we finally came upon one soul, a lone goat who had become separated from his flock, scampering amidst the forest and some earth mounds from what looked like delayed construction work. The road now took on an unfinished look. Piles of gravel lay by the side of the road which had not been tarmacked. Till now, I had been doing the driving, but at this point, I asked to be excused. For such a supposedly significant landmark that had been in the area for more than fifty years, it did not seem possible that the road towards it was only now being constructed! Some of the mountainsides looked as though they had been ironed flat by heavy machinery; the traces of their wheels were still embedded on their slopes.

The sight of a water body, be it a river, a lake or the sea itself, is a point of climax for landlocked travellers. Thalatta! Thalatta! Mountains display awesome wonder, but water gives life. The dangers that a watery mass may hide are concealed within its depths. And so it was with us when we first sighted Limni Kremaston. We pulled over as soon as we found a safe spot by a rocky but fertile hill where bricks, dirt and cement had been dumped, desecrating this holy lookout spot of the first sighting of what looked like a wonder of the world. The wind was now whipping through our skins. A rainshower was imminent judging by the thick black masses in the sky.

The little islets floated like dazzling emeralds on a sapphire blanket. The waters were calm and stable, not a single movement was visible. "Put your jackets on, kids!" They didn't need to be told; the drop in temperature was highly discernible. They had already put them on before I told them to. The lake district seemed to stretch out for what looked like miles to us - but not a single house was visible. Where have all the people gone, I wondered. There was only one building in the area, an ugly-looking edifice made of cheap modern construction materials in no particular design; it was probably a shed of some sort used for storage, or maybe as a shelter for animals. The area looked quite fertile, with low-lying shrubs and a few randomly planted trees. But it also looked abandoned. Not a soul in sight, not even a cafe or taverna, even though the view from this point was splendidly breathtaking. What was considered to be a life source was itself lifeless. The little islands of the lake lost their dazzle. They now looked as though they were slowly being eaten away, their lower edges showing evidence of erosion from the rising and falling waters. My belief that we'd be sipping frappe at this moment while taking in the amazing views was quite far off the mark.

The little islets floated like dazzling emeralds on a sapphire blanket. The waters were calm and stable, not a single movement was visible. "Put your jackets on, kids!" They didn't need to be told; the drop in temperature was highly discernible. They had already put them on before I told them to. The lake district seemed to stretch out for what looked like miles to us - but not a single house was visible. Where have all the people gone, I wondered. There was only one building in the area, an ugly-looking edifice made of cheap modern construction materials in no particular design; it was probably a shed of some sort used for storage, or maybe as a shelter for animals. The area looked quite fertile, with low-lying shrubs and a few randomly planted trees. But it also looked abandoned. Not a soul in sight, not even a cafe or taverna, even though the view from this point was splendidly breathtaking. What was considered to be a life source was itself lifeless. The little islands of the lake lost their dazzle. They now looked as though they were slowly being eaten away, their lower edges showing evidence of erosion from the rising and falling waters. My belief that we'd be sipping frappe at this moment while taking in the amazing views was quite far off the mark.

We got back into the car and made our way to the bridge, which turned out to be one of the most uninspiring constructions I have ever laid eyes on: tarmacked concrete with ugly but very functional yellow railings. There was nowhere to park on the bridge, not even a lookout point, but this did not surprise me. We had already discovered that we were in no danger of meeting any oncoming traffic. We were alone here, completely by ourselves. We stopped in the middle of our lane on the dual carriage-way and all got out of the car. The bridge connected the two different sides of the lake at their narrowest point, so that the vastness of the water body was not immediately visible to us. But still, it was a magical view, so much serenity packed in one remote corner of Greece; awesome, but at the same time, eerie.

"Where are they coming from?" my husband was asking me. At first I didn't understand what he meant; I was keeping an eye on the children - the railings had many openings. Eventually I heard the ringing of bells; there must be a church close by which was not discernible within our range of visibility. The stillness of the water was surrounded by mountains which had been cut away to form the lake where four rivers met: Acheloos, Agrafiotis, Tavropos and Trikeriotis, to create the narrow gorge below us. What lay on the lake bed was anyone's guess.

"Where are they coming from?" my husband was asking me. At first I didn't understand what he meant; I was keeping an eye on the children - the railings had many openings. Eventually I heard the ringing of bells; there must be a church close by which was not discernible within our range of visibility. The stillness of the water was surrounded by mountains which had been cut away to form the lake where four rivers met: Acheloos, Agrafiotis, Tavropos and Trikeriotis, to create the narrow gorge below us. What lay on the lake bed was anyone's guess.

"Look, I can see my face in the lake, Mum." I was so distracted by the silence that I didn't see my son crouching down with his face in between the railings, peering into the water.

"Get up!" I shouted. "Get up now! What you're doing is dangerous!"

"But look," he insisted, "you can't see it otherwise if you don't stare into the water. Look," he urged his sister, "it's like a mirror!"

I crouched down near him and looked down, but I saw nothing, maybe because I didn't have a child's imaginative powers. He was creating a tale, making up stories like most little boys, probably to scare his younger sister into believing that there could be some kind of bodyless apparation waiting to rise up from the waters and grab them both, plunging them into the unknown depths of the lake.

"You're lying," she said to him, not daring to look down. I couldn't blame her. The church bells were still ringing, adding to the suspense. And they weren't just clanging: the sounds that they were making were definitely the mourning toll, known to every Greek, the sound of the arrival of death, with a funeral ensuing.

The wind was now lashing us all at our napes. I cuddled the children together to keep them warm, trying to avoid the subconscious thought in my mind that they could accidentally slip between the rails.

"Oy!" my son screamed out, his voice echoing across the valley. "Stop poking me!" He was roaring into his sister's ear, slapping her across the back.

"Did not!' she spat back, taking her revenge with a kick to his shin.

"Stop it!" I screamed. "At once!" Their father was not within earshot. He had already walked to the other side of the bridge and was oblivious to what was happening.

I was now in a state of panic myself; calling out to my husband to return to the car. He turned round slowly, as if responding to my calls. He was looking up at the sky, huddling himself. The kids were now blowing punches at each other.

"In the car! Now! We're leaving!" I was shoving them in the direction of the car.

I didn't really feel the need to stay any longer anyway. Even if I carried on staring out into the open space, I would not have seen anything new. Under the grey clouds of the sky, there was the clear blue colour of the lake, the verdant green peaks of the hills, and the stark brown eroded foothills of the mountains, showing where the water had recently reached. There was nothing else to see.

"Seatbelts!" I reminded the kids, hoping that this would stop them from continuing to fight over an imaginary poke, but it did not appease them. They were hurling insults at one another, screaming here, howling there, continuing the melee. Despite the cacophony, the church bells could still be heard. My husband was now walking back at trotting pace. What was he running for? I turned the ignition and set the window wipers to work to clear the drops of water that were running in small rivulets down the screen. It was at that moment that I froze. The windscreen was wet. But it hadn't rained all the while that we were on the bridge.

Despite my state of panic, I managed to get the car started. My husband jumped in and closed the door hurriedly. He looked as white as a sheet - and his was jacket looked soaked.

"Don't tell me it was raining," I said jokingly. "None of us are wet. What happened to you?"

"What do you mean you aren't wet? It's been raining. Look," he pointed to the windscreen, "and it's still raining," he repeated, his voice breaking off suddenly. The windscreen was now dry. The wipers were working against a clear background. "Well, it looks as though it's stopped now," he added.

I looked at my clothes. They were dry, not a hint of damp. So were the children's when I turned round to look at them. Only my husband's jacket was wet. So was his hair. Putting on a brave face, I turned on the engine. There was no point arguing in the car over a bridge in the middle of nowhere about the weather forecast.

"OK, let's get out of here," I said, "this place gives me the creeps." I drove as steadily as the past series of shocks allowed me to, noting that the bridge looked dry, even though the clouds were black and heavy, ready to pour buckets over the area. The children were still fighting, but this time their voices were raised above the tolerance level.

"SHUT UP!" I screamed, slamming on the brakes. The car began to wobble, the tyres making a screeching sound as they skidded. We were centimetres away from coming off the bridge.

"What the HELL are you DOING?" my husband cried. "Get off the wheel! I'm driving!" He threw open the door of the car and marched to the driver's side. The children were now sulking silently; the whole drama had diverted our attention away from the rain. I tried to make light conversation.

"The bell ringing seems to have stopped, hasn't it?" Dimitri showed no interest in what I was saying. I browsed at the map as he drove off.

"It's your fault we're here," he began to accuse me. "Driving all the way here to see a lake," he muttered. "As if you've never seen one before."

"Well," I started, "if you're trying to tell me that Lake Kournas is the same thing as this one, I'd say you were nuts." Without responding to my statement, he continued to drive, looking straight ahead.

"Oh look," I pointed to the sign as we drove off the bridge. "A cafe." I doubted he'd want to stop over, but then again, I didn't feel like stopping either. It had that desolate shut-down look that most of the houses in the area also had, but there was a car in the small open space next to the premises, presumably the owner's. The road now looked wet. Not doubt, it had been raining here.

"There's a monastery tucked somewhere along this road," I continued. "That must be where the sound of the bell ringing was coming from," I added helpfully.

"The bells were ringing from the other side of the valley, not from here," he scoffed, mockingly.

"Yeah, Mum," his son agreed with him. "They weren't coming from here.

Wherever those bells were ringing, they had now stopped. The funeral had probably already started. But church bells were common in this part of the country, as I was to find out when we finally arrived in Karpenisi, just before darkness began to fall over the town. The telephone lines were also working. I had no problem sending Hrisida a message now: "See you very soon", I typed, just as the first houses of the slopes of the hills that Karpenisi was built on came into view.

*** *** ***

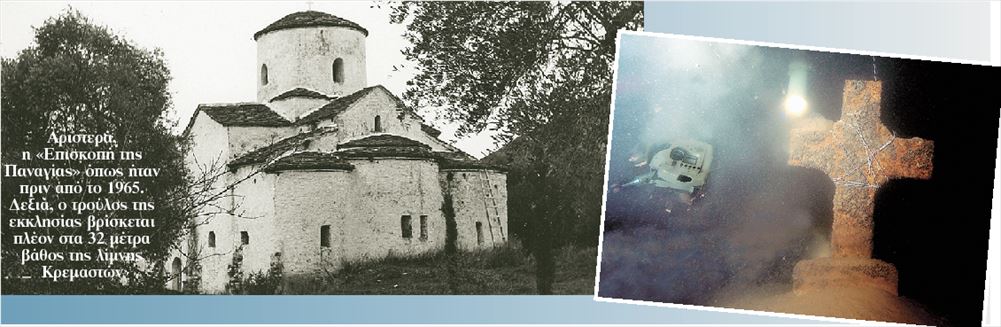

Before the lake was created in the

1960s, that area used to be the plain of Evrytania as it was

relatively flatter and fertile, full of villages, with a mild climate created by the rivers. The people who were born in the area bordering the prefectures of Evritania and Aitoloakarnania, along with their ancestry, were forced to evacuate

their birthplaces. In July 1965, twenty villages were wiped off the map of Greece, along with dozens of churches and monasteries and a series of cultivations covering 90,000 stremma of land. They all "drowned" when the waters of the artificial Kremasta Lake became the damp grave where everything those villagers knew about the world, everything they held precious and dear, was buried in its depths. The evacuees were given some kind of compensation in

return, but it was very small, as things usually work out for such victims. From the photos of the evacuation process, it is chilling to see the despair of the people; they look like war

refugees, and to think, they had lived through WW2, and barely survived the Greek civil war

that was fought very harshly in those mountains, when they were made refugees by a

democratically elected government! When the lake was created, a couple of strong earthquakes in

the area caused by the water seeping into the ground rounded the picture

of abandonment. Land was provided in Karpenisi to house those affected by the formation of the lake, the earthquakes and the landslides. It was then that the region of Agrafa close to the lake district was

abandoned by its inhabitants. That's why there are no villages around

the lake; they are all lying on the lake bed. The remaining few

that are on the slopes are slowly sliding towards the lake too. DEH, the national Greek electricity company (there is still a monopoly in this sector), has ownership of the land around the lake and didn't actually favour the resettlement of the evacuees there since they

wouldn't

like people complaining that the villages are

sliding towards the lake and asking for compensation. As the saying

goes "όπου φτωχός κι η μοίρα του".

Before the lake was created in the

1960s, that area used to be the plain of Evrytania as it was

relatively flatter and fertile, full of villages, with a mild climate created by the rivers. The people who were born in the area bordering the prefectures of Evritania and Aitoloakarnania, along with their ancestry, were forced to evacuate

their birthplaces. In July 1965, twenty villages were wiped off the map of Greece, along with dozens of churches and monasteries and a series of cultivations covering 90,000 stremma of land. They all "drowned" when the waters of the artificial Kremasta Lake became the damp grave where everything those villagers knew about the world, everything they held precious and dear, was buried in its depths. The evacuees were given some kind of compensation in

return, but it was very small, as things usually work out for such victims. From the photos of the evacuation process, it is chilling to see the despair of the people; they look like war

refugees, and to think, they had lived through WW2, and barely survived the Greek civil war

that was fought very harshly in those mountains, when they were made refugees by a

democratically elected government! When the lake was created, a couple of strong earthquakes in

the area caused by the water seeping into the ground rounded the picture

of abandonment. Land was provided in Karpenisi to house those affected by the formation of the lake, the earthquakes and the landslides. It was then that the region of Agrafa close to the lake district was

abandoned by its inhabitants. That's why there are no villages around

the lake; they are all lying on the lake bed. The remaining few

that are on the slopes are slowly sliding towards the lake too. DEH, the national Greek electricity company (there is still a monopoly in this sector), has ownership of the land around the lake and didn't actually favour the resettlement of the evacuees there since they

wouldn't

like people complaining that the villages are

sliding towards the lake and asking for compensation. As the saying

goes "όπου φτωχός κι η μοίρα του".

Kostas Balafas had the opportunity to photograph the area as the lake was being shaped. He writes:

http://www.panoramio.com/photo/9646081

http://www.costasbalafas.gr/index.php (Kostas Balafas used to work for DEH, and as an avid photographer, he had direct access to the hydroelectric project's progress, hence the good documentation of the project through his lens)

UPDATE: I asked Hrisida to read this story before I posted it and she told me: "It's not uncommon here when it rains and you are driving to reach a point on the road where there is a dividing line of wet and dry tarmac."

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.

Before visiting the artificially created Kremasta Lake, I had no knowledge about it whatsoever.

*** ***

After a refreshing gazoza by the old romantic bridge of Arta, we set off on to our next destination: Karpenisi, a town set on the slopes of forested mountains in Central Greece. The weather was so hot you could bake bread under a tin roof. The stuffy air left us gasping; time to turn on the air conditioner of the trusty loyal family car, a battered 12-year-old Hyundai Accent, laden with suitcases. We were in for a bumpy ride through the largely unexplored countryside of Central Greece. Τhe route my friend had dictated to me was considered uncharted territory on my 20-year-old map, the one I was still using from the time I first arrived in Greece. We had been considering buying a GPS for a while now. Its purchase is still pending: we are waiting to buy the new car first.

My friend Hrisida sent me a text message explaining the route: "Arta - Komboti - Halkiopoulo - Tatarnas Bridge - Loggitsi - Krenti - Kerasohori - Karpenisi. You will find Lake Kremaston very impressive."

"There's no real arterial route from Arta to Karpenisi," Hrisida had warned me. "Μην βραδιαστείτε" was her main advice: don't let nightfall come. We stopped off at a petrol station to buy a new map. Good thing we did this early enough: petrol stations from Arta to Karpenisi are very hard to come by. Exiting Arta from the busy road by the impressive castle ruins leading out of the city, we remained chained to a line of traffic until we reached Sellades. Just after passing the Komboti junction, we left the modern world behind us. We were about to enter the depths of rural Greece, where the physical presence of humans had become a form of sport: human-spotting.

The densely forested damp mountains that we had travelled through in Epirus, with their low-lying clouds suspended among the hills and gushing rivers, even at this time of year (end of summer), suddenly gave way to the rocky mountains of Aitoloakarnania, some of them green and forested, others looking sunburnt from their barrenness. The road was winding interminably round hills that seemed to lead to nowhere. Villages were labelled on the map by name, but not necessarily signposted.

"Are you sure this is the right road?" my husband kept asking me. Yes, I felt sure this was the right road, since there seemed to be no other road to take. We looked out for the next sighting of houses. It never came early enough. The map said: "Katharovouni" but either we had blinked when we had passed the sign (or the houses) or it was simply not there. It was a case of either continuing to drive, or returning from the road we came from. We chose the former. The narrow roads did not make allowances for U-turns, being located dangerously either by a badly maintained ditch or at the outer edge of a precipice. We drove sometimes up, sometimes down, but always less than 50km/hour, often wondering if we were actually on the right road. We were in the middle of nowhere.

In that nowhere, we came across what looked like a newly-built kiosk, a wooden structure with seating arranged in a circle, with a tiled roof over it to block out the sun. Kiosks of this sort aren't rare in mountain country, but they are usually attached to a church, or maybe a housing settlement. In our case, there was nothing of the sort. It looked as though it was there to allow people to take in the panoramic sight of a series of mountains and hills backdropping against each other, each one fading into the horizon. No houses nearby, just the kiosk - and there was our first sighting of a human. "Always stop and ask for directions," Hrisida kept reminding me when she heard that I was planning this trip. We pulled over by the side of a steep cliff-hanging road. By now, we had stopped fearing for oncoming traffic; if that did actually happen, it would be a miracle in the outback country.

He looked quite young, no more than fifteen years old. He was sitting on the top of the back-supporting part of a bench talking into a mobile phone. What he was doing out here was none of our business. Presumably this spot had a good signal. It was also a good spot to get sunstroke just by staring up at the sky - the stark environment was blinding under the hot morning sun.

"Excuse me," my husband called out to the young man. "Can you tell me which is the next village?" my husband asked him. The boy stared at us, as if surprised to be interrupted. My husband repeated the question. The boy looked puzzled: he didn't know what the next village was.

"I'm from the Rahi", he explained to us. We looked for "Rahi" on the map, but there seemed to be no such place. The boy could not even place himself on the map when we asked him to show us where we were. He simply pointed towards an undefined direction in the air. No housing settlement was visible from where we were standing. My husband then tried another question tactic, a trick he had learnt over the years as a taxi driver: instead of asking the name of the next village, he asked him how long it would take to get to a village that was actually on the map:

"How far is Floriada from here?"

"Flo-what? Floyada?" The boy acted as though he had never heard of Floriada. His presence as a stranger to these parts of the remote mountain road felt sinister. We said goodbye to him, got back into the car and continued driving. A derelict house came into view after a few minutes of very slow driving round the bends, the ruins of a stone-built cottage. Then a little further on another one. And finally, what we were looking for: a faded signpost announcing 'Floriada", and then, a few well-kept properties whose shutters looked as though they had not been opened for quite some time. At least we knew we were on the right road.

*** *** ***

Driving along empty Greek roads is not as perturbing as it sounds. It gives you time to stop and look at anything that takes your fancy. You can also take in the changes encountered on the journey. As we continued to wind up and down this remote part of the countryside, we came to understand what the words αγρότη and μοναξιά would mean in this area of Greece. Disused agricultural machinery and ancient vehicle models lined the unsignposted road, bordered by sometimes bare, sometimes forested hills and mountains on either side, with only a few houses, sometimes scattered on the hills, other times clustered in what looked to be a ghost town. It came as almost a shock when we saw a large party dining outside under the shade of a grapevine at one point. What were they doing here? Where did they work? What were they living off? Did the mailman pass by their house on a daily basis? The condition of the roads led me to believe that these people never left their homes for long, never went too far away from their houses. They were living as though they did not exist. If it weren't for the telephone, they would be forgotten.

We noted the change in the scenery as we drove on: just like the scenery, the weather also began to change. The bare mountainsides gave way to thick forests with fir trees, which blocked out the sun's rays, cooling down the air, and making driving conditions more bearable. I imagined the scene in winter: fir trees covered in snow, a perfect Christmas image. This change of scenery also signalled our entry into another prefecture: from Arta in Epirus, we crossed into Aitoloakarnania, and now we were heading towards Evritania. It is not difficult to understand why Greeks sometimes do not understand their compatriots spread across the country - the people change as the scenery changes. Every now and then, we would come across a few goats on the road. They would make the best climbers in these parts. The shepherds tending the flocks were nowhere in sight but occasionally we would come across a pick-up truck on the road.

Eventually we came across what looked like a meeting spot. It didn't resemble a village square, but it seemed a perfect place to set up a small canteen van by the side of the road, next to a petrol station, for the occasional passersby to indulge in a bite to eat and a person to chat to. But how often did people pass this spot? It reminded me of another piece of advice that Hrisida had given me before the trip: "Δεν θα συναντήσεις ψυχή στο δρόμο"; 'you will not meet a soul on the road.' The whole time we had been on the road, we can't have seen more than ten cars. As this thought occurred to me, the pervasive silence of the area also began to infiltrate my mind. It was eerily quiet in these here parts. To add to the uncanniness of the situation, the whole time we were driving to our point of interest, it was sweltering. But as we began to draw closer to our destination, the wind began to rise, a few raindrops fell on the windscreen, and the sky lost its brightness.

The mountainsides were now mainly forested, giving a very fertile look to the area. Rock and boulder masses denoted the presence of streams and rivers, all leading to their final depository, Lake Kremaston; we were waiting for it to come into view, and we had now all become impatient. Where was that lake hiding?

The mountainsides were now mainly forested, giving a very fertile look to the area. Rock and boulder masses denoted the presence of streams and rivers, all leading to their final depository, Lake Kremaston; we were waiting for it to come into view, and we had now all become impatient. Where was that lake hiding? I took out my cell phone to send a message to Hrisida. "Approaching Tatarnas," I typed, and clicked on the Send icon. The lake had still not come into view.

BIP! Message received, I thought. But I got a surprise when I looked at the screen. "Message not sent" had popped up on it. There was no signal. It was probably the only time I had no phone signal throughout our summer holiday. That's when fear overcomes you: no signal means you can't even ask for help if you get stuck in a ditch, or come across other trouble, like a wolf or boar straying out of the forest; I felt a sense of relief that it wasn't raining.

The sight of a water body, be it a river, a lake or the sea itself, is a point of climax for landlocked travellers. Thalatta! Thalatta! Mountains display awesome wonder, but water gives life. The dangers that a watery mass may hide are concealed within its depths. And so it was with us when we first sighted Limni Kremaston. We pulled over as soon as we found a safe spot by a rocky but fertile hill where bricks, dirt and cement had been dumped, desecrating this holy lookout spot of the first sighting of what looked like a wonder of the world. The wind was now whipping through our skins. A rainshower was imminent judging by the thick black masses in the sky.

The little islets floated like dazzling emeralds on a sapphire blanket. The waters were calm and stable, not a single movement was visible. "Put your jackets on, kids!" They didn't need to be told; the drop in temperature was highly discernible. They had already put them on before I told them to. The lake district seemed to stretch out for what looked like miles to us - but not a single house was visible. Where have all the people gone, I wondered. There was only one building in the area, an ugly-looking edifice made of cheap modern construction materials in no particular design; it was probably a shed of some sort used for storage, or maybe as a shelter for animals. The area looked quite fertile, with low-lying shrubs and a few randomly planted trees. But it also looked abandoned. Not a soul in sight, not even a cafe or taverna, even though the view from this point was splendidly breathtaking. What was considered to be a life source was itself lifeless. The little islands of the lake lost their dazzle. They now looked as though they were slowly being eaten away, their lower edges showing evidence of erosion from the rising and falling waters. My belief that we'd be sipping frappe at this moment while taking in the amazing views was quite far off the mark.

The little islets floated like dazzling emeralds on a sapphire blanket. The waters were calm and stable, not a single movement was visible. "Put your jackets on, kids!" They didn't need to be told; the drop in temperature was highly discernible. They had already put them on before I told them to. The lake district seemed to stretch out for what looked like miles to us - but not a single house was visible. Where have all the people gone, I wondered. There was only one building in the area, an ugly-looking edifice made of cheap modern construction materials in no particular design; it was probably a shed of some sort used for storage, or maybe as a shelter for animals. The area looked quite fertile, with low-lying shrubs and a few randomly planted trees. But it also looked abandoned. Not a soul in sight, not even a cafe or taverna, even though the view from this point was splendidly breathtaking. What was considered to be a life source was itself lifeless. The little islands of the lake lost their dazzle. They now looked as though they were slowly being eaten away, their lower edges showing evidence of erosion from the rising and falling waters. My belief that we'd be sipping frappe at this moment while taking in the amazing views was quite far off the mark.We got back into the car and made our way to the bridge, which turned out to be one of the most uninspiring constructions I have ever laid eyes on: tarmacked concrete with ugly but very functional yellow railings. There was nowhere to park on the bridge, not even a lookout point, but this did not surprise me. We had already discovered that we were in no danger of meeting any oncoming traffic. We were alone here, completely by ourselves. We stopped in the middle of our lane on the dual carriage-way and all got out of the car. The bridge connected the two different sides of the lake at their narrowest point, so that the vastness of the water body was not immediately visible to us. But still, it was a magical view, so much serenity packed in one remote corner of Greece; awesome, but at the same time, eerie.

"Look, I can see my face in the lake, Mum." I was so distracted by the silence that I didn't see my son crouching down with his face in between the railings, peering into the water.

"Get up!" I shouted. "Get up now! What you're doing is dangerous!"

"But look," he insisted, "you can't see it otherwise if you don't stare into the water. Look," he urged his sister, "it's like a mirror!"

I crouched down near him and looked down, but I saw nothing, maybe because I didn't have a child's imaginative powers. He was creating a tale, making up stories like most little boys, probably to scare his younger sister into believing that there could be some kind of bodyless apparation waiting to rise up from the waters and grab them both, plunging them into the unknown depths of the lake.

"You're lying," she said to him, not daring to look down. I couldn't blame her. The church bells were still ringing, adding to the suspense. And they weren't just clanging: the sounds that they were making were definitely the mourning toll, known to every Greek, the sound of the arrival of death, with a funeral ensuing.

The wind was now lashing us all at our napes. I cuddled the children together to keep them warm, trying to avoid the subconscious thought in my mind that they could accidentally slip between the rails.

"Oy!" my son screamed out, his voice echoing across the valley. "Stop poking me!" He was roaring into his sister's ear, slapping her across the back.

"Did not!' she spat back, taking her revenge with a kick to his shin.

"Stop it!" I screamed. "At once!" Their father was not within earshot. He had already walked to the other side of the bridge and was oblivious to what was happening.

I was now in a state of panic myself; calling out to my husband to return to the car. He turned round slowly, as if responding to my calls. He was looking up at the sky, huddling himself. The kids were now blowing punches at each other.

"In the car! Now! We're leaving!" I was shoving them in the direction of the car.

I didn't really feel the need to stay any longer anyway. Even if I carried on staring out into the open space, I would not have seen anything new. Under the grey clouds of the sky, there was the clear blue colour of the lake, the verdant green peaks of the hills, and the stark brown eroded foothills of the mountains, showing where the water had recently reached. There was nothing else to see.

"Seatbelts!" I reminded the kids, hoping that this would stop them from continuing to fight over an imaginary poke, but it did not appease them. They were hurling insults at one another, screaming here, howling there, continuing the melee. Despite the cacophony, the church bells could still be heard. My husband was now walking back at trotting pace. What was he running for? I turned the ignition and set the window wipers to work to clear the drops of water that were running in small rivulets down the screen. It was at that moment that I froze. The windscreen was wet. But it hadn't rained all the while that we were on the bridge.

Despite my state of panic, I managed to get the car started. My husband jumped in and closed the door hurriedly. He looked as white as a sheet - and his was jacket looked soaked.

"Don't tell me it was raining," I said jokingly. "None of us are wet. What happened to you?"

"What do you mean you aren't wet? It's been raining. Look," he pointed to the windscreen, "and it's still raining," he repeated, his voice breaking off suddenly. The windscreen was now dry. The wipers were working against a clear background. "Well, it looks as though it's stopped now," he added.

I looked at my clothes. They were dry, not a hint of damp. So were the children's when I turned round to look at them. Only my husband's jacket was wet. So was his hair. Putting on a brave face, I turned on the engine. There was no point arguing in the car over a bridge in the middle of nowhere about the weather forecast.

"OK, let's get out of here," I said, "this place gives me the creeps." I drove as steadily as the past series of shocks allowed me to, noting that the bridge looked dry, even though the clouds were black and heavy, ready to pour buckets over the area. The children were still fighting, but this time their voices were raised above the tolerance level.

"SHUT UP!" I screamed, slamming on the brakes. The car began to wobble, the tyres making a screeching sound as they skidded. We were centimetres away from coming off the bridge.

"What the HELL are you DOING?" my husband cried. "Get off the wheel! I'm driving!" He threw open the door of the car and marched to the driver's side. The children were now sulking silently; the whole drama had diverted our attention away from the rain. I tried to make light conversation.

"The bell ringing seems to have stopped, hasn't it?" Dimitri showed no interest in what I was saying. I browsed at the map as he drove off.

"It's your fault we're here," he began to accuse me. "Driving all the way here to see a lake," he muttered. "As if you've never seen one before."

"Well," I started, "if you're trying to tell me that Lake Kournas is the same thing as this one, I'd say you were nuts." Without responding to my statement, he continued to drive, looking straight ahead.

"Oh look," I pointed to the sign as we drove off the bridge. "A cafe." I doubted he'd want to stop over, but then again, I didn't feel like stopping either. It had that desolate shut-down look that most of the houses in the area also had, but there was a car in the small open space next to the premises, presumably the owner's. The road now looked wet. Not doubt, it had been raining here.

"There's a monastery tucked somewhere along this road," I continued. "That must be where the sound of the bell ringing was coming from," I added helpfully.

"The bells were ringing from the other side of the valley, not from here," he scoffed, mockingly.

"Yeah, Mum," his son agreed with him. "They weren't coming from here.

Wherever those bells were ringing, they had now stopped. The funeral had probably already started. But church bells were common in this part of the country, as I was to find out when we finally arrived in Karpenisi, just before darkness began to fall over the town. The telephone lines were also working. I had no problem sending Hrisida a message now: "See you very soon", I typed, just as the first houses of the slopes of the hills that Karpenisi was built on came into view.

*** *** ***

Before the lake was created in the

1960s, that area used to be the plain of Evrytania as it was

relatively flatter and fertile, full of villages, with a mild climate created by the rivers. The people who were born in the area bordering the prefectures of Evritania and Aitoloakarnania, along with their ancestry, were forced to evacuate

their birthplaces. In July 1965, twenty villages were wiped off the map of Greece, along with dozens of churches and monasteries and a series of cultivations covering 90,000 stremma of land. They all "drowned" when the waters of the artificial Kremasta Lake became the damp grave where everything those villagers knew about the world, everything they held precious and dear, was buried in its depths. The evacuees were given some kind of compensation in

return, but it was very small, as things usually work out for such victims. From the photos of the evacuation process, it is chilling to see the despair of the people; they look like war

refugees, and to think, they had lived through WW2, and barely survived the Greek civil war

that was fought very harshly in those mountains, when they were made refugees by a

democratically elected government! When the lake was created, a couple of strong earthquakes in

the area caused by the water seeping into the ground rounded the picture

of abandonment. Land was provided in Karpenisi to house those affected by the formation of the lake, the earthquakes and the landslides. It was then that the region of Agrafa close to the lake district was

abandoned by its inhabitants. That's why there are no villages around

the lake; they are all lying on the lake bed. The remaining few

that are on the slopes are slowly sliding towards the lake too. DEH, the national Greek electricity company (there is still a monopoly in this sector), has ownership of the land around the lake and didn't actually favour the resettlement of the evacuees there since they

wouldn't

like people complaining that the villages are

sliding towards the lake and asking for compensation. As the saying

goes "όπου φτωχός κι η μοίρα του".

Before the lake was created in the

1960s, that area used to be the plain of Evrytania as it was

relatively flatter and fertile, full of villages, with a mild climate created by the rivers. The people who were born in the area bordering the prefectures of Evritania and Aitoloakarnania, along with their ancestry, were forced to evacuate

their birthplaces. In July 1965, twenty villages were wiped off the map of Greece, along with dozens of churches and monasteries and a series of cultivations covering 90,000 stremma of land. They all "drowned" when the waters of the artificial Kremasta Lake became the damp grave where everything those villagers knew about the world, everything they held precious and dear, was buried in its depths. The evacuees were given some kind of compensation in

return, but it was very small, as things usually work out for such victims. From the photos of the evacuation process, it is chilling to see the despair of the people; they look like war

refugees, and to think, they had lived through WW2, and barely survived the Greek civil war

that was fought very harshly in those mountains, when they were made refugees by a

democratically elected government! When the lake was created, a couple of strong earthquakes in

the area caused by the water seeping into the ground rounded the picture

of abandonment. Land was provided in Karpenisi to house those affected by the formation of the lake, the earthquakes and the landslides. It was then that the region of Agrafa close to the lake district was

abandoned by its inhabitants. That's why there are no villages around

the lake; they are all lying on the lake bed. The remaining few

that are on the slopes are slowly sliding towards the lake too. DEH, the national Greek electricity company (there is still a monopoly in this sector), has ownership of the land around the lake and didn't actually favour the resettlement of the evacuees there since they

wouldn't

like people complaining that the villages are

sliding towards the lake and asking for compensation. As the saying

goes "όπου φτωχός κι η μοίρα του".Kostas Balafas had the opportunity to photograph the area as the lake was being shaped. He writes:

"At the river Acheloos, the first borders of the modern Greek state were formed. The first hand-written newspaper that went into circulation was called 'Acheloos'. This wild river, whose floods spread destruction, was tamed by modern technology and transformed into energy and power for the common good of the Greek people. But large projects that have to do with the economy and nationalism also carry a large cost, a fate which always falls on the poor. This was a battle between man and the natural elements; at least thirty workers were killed, with many more wounded or losing a limb, remaining paralysed for the rest of their lives. Noble villages like Episkopi, St Vasilios, Mavrias, Sidera and Sivista were drowned in the waters of the lake, and their residents were uprooted from their paternal hearths. I happened to live through the drama of the people's uprooting. Many took whatever was useful from their torn-down home, and spread themselves in the surrounding villages, where they had relatives and acquaintances, while some built huts on the outskirts of the project area. Most took the road for the valley. They opened up the graves and took out the bones of their ancestors, placing them in clean sheets, together with anything precious that they could carry, hugging it closely together with their tragic fate, in search of a new homeland, where they could root themselves again, having left behind the place where they had lived all their lives, their heart full of bitterness, where there was no more room for so much pain."

You can find many more poignant photography showing the people involved in the evacuation of the area and the construction of the Kremasta earth dam (at a historically significant location, the narrowest point of the river Acheloos, in an area known as "Katsantonis' Leap") in Kostas Balafas' book, starting on page 73.

All photos not my own come from the following sites:

http://tvxs.gr/taxonomy/term/33015

http://acarnania.blogspot.com/2011/01/blog-post_2201.html

http://mw2.google.com/mw-panoramio/photos/medium/5931194.jpg You can find many more poignant photography showing the people involved in the evacuation of the area and the construction of the Kremasta earth dam (at a historically significant location, the narrowest point of the river Acheloos, in an area known as "Katsantonis' Leap") in Kostas Balafas' book, starting on page 73.

All photos not my own come from the following sites:

http://tvxs.gr/taxonomy/term/33015

http://acarnania.blogspot.com/2011/01/blog-post_2201.html

http://www.panoramio.com/photo/9646081

http://www.costasbalafas.gr/index.php (Kostas Balafas used to work for DEH, and as an avid photographer, he had direct access to the hydroelectric project's progress, hence the good documentation of the project through his lens)

UPDATE: I asked Hrisida to read this story before I posted it and she told me: "It's not uncommon here when it rains and you are driving to reach a point on the road where there is a dividing line of wet and dry tarmac."

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria Verivaki.