The photos seem to have gone astray: you can find them by clicking on this link. Use the previous/next buttons to see more photos.

My friend Hrisida has been at it again, giving me some more ideas for using home-made filo pastry, thereby improving my technique. She mentioned how much she liked galatopita, a sweet custard pie made in Northern Greece. Here in Hania (and probably throughout Crete), the word 'galatopita' is not even heard. I had tried galatopita in Karpenisi when I visited the area last summer; to me, it tasted simply like a 'dairy' pie (it was hard to work out if it was made with milk or cheese).

When googling a recipe, I always check the images. After picking the galatopita photos that I liked, I then opened the page of whichever one took my fancy. Here's what I found:

- some use no filo at all (they're baked like a custard)

- some use filo only on the bottom (they're baked like a pie)

- some use filo both on top and at the bottom (like the one I tried in Karpenisi)

- some pour syrup over the baked (filo or filo-less) pie (in other words, they turn out like a galaktoboureko).

There were also some interesting variations, eg nuts/dried fruit in the custard, flavoured custard (notably chocolate) and variations on the way the pita is presented (eg cigar-shaped roll-ups).

Of all the recipes, I have to say that I liked the chocolate galatopita most of all, with its airy-looking crust. The combination and contrast of the pale fyllo and dark custard made it look quite pretty, and very festive. It would make a spectacular Christmas dessert, made as individual servings. It's been a while since I used my ramekin set; now is the perfect time to take them out. The following recipe is based on Asproula's galatopita recipe (in Greek); she also makes her own filo pastry for all her pitas.

Warm the milk in a saucepan, then add the semolina, stirring continuously so that the mixture doesn't stick to the saucepan, and making sure that it doesn't go lumpy, until it thickens to a cream. Turn off the heat and allow the cream to cool slightly. Add the butter, sugar and sifted cocoa and mix well. Finally beat in the eggs and whisk them into the cream, blending everything well.

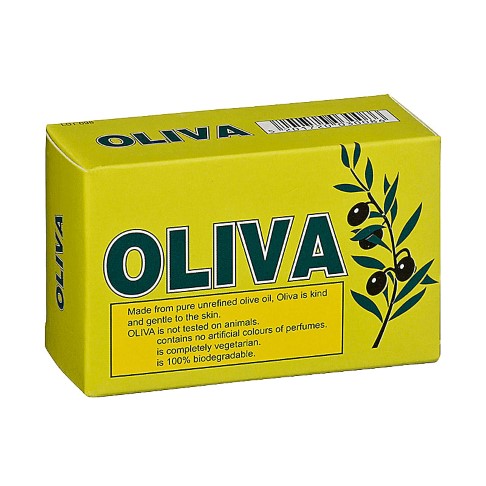

Grease your ramekins (I use olive oil: you can use butter) and line each one with a small piece of filo pastry, leaving a little (but not too much) pastry hanging over the edge of the ramekins. Grease the filo well and then lay another piece of pastry on top of it. Sprinkle each ramekin with a little sugar and cinnamon (which I forgot to do!), then fill each one carefully (so as not to stain the edges of the filo, like I did!) with the creamy mixture. Try to make the filo pastry stick decoratively over the edge of the ramekins (this will be easier with store-bought filo pastry); grease these pastry bits well. Place the ramekins in the oven on the lowest rack and bake in moderate heat (180C) for approximately 35-40 minutes, until the cream has set. Turn off the oven, let the galatopita ramekins sit for a few minutes to solidify, and then remove them.

Serve the galatopita cool - it tastes much better at room temperature. The galatopitoules come clean out of the ramekins, but they can also be served in them (recommended if you have baked them 'naked', ie without filo; otherwise, the filo pita needs to be cut). Galatopita can be eaten slightly warm or cold and can be reheated. It's sometimes sprinkled with sugar and/or cinnamon; I served them with some red berry fruit (mulberry spoon sweet from Northern Pilio) and nuts. Another nice idea would be to crumble some tahini-based Macedonian halva over them (if this is available where you are) for extra sweetness.

Another bi-coloured festive variation to this pie would be to make chocolate-flavoured filo pastry (add some cocoa powder to the flour) and omit the cocoa from the custard. It will also surprise your guests and they will think you are a celebrity chef.

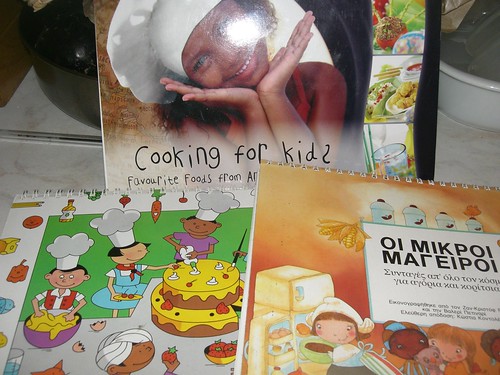

Bonus holiday recipes, from my friends:

My friend Hrisida has been at it again, giving me some more ideas for using home-made filo pastry, thereby improving my technique. She mentioned how much she liked galatopita, a sweet custard pie made in Northern Greece. Here in Hania (and probably throughout Crete), the word 'galatopita' is not even heard. I had tried galatopita in Karpenisi when I visited the area last summer; to me, it tasted simply like a 'dairy' pie (it was hard to work out if it was made with milk or cheese).

Galatopita is the first pita on the left (after that, it's spanakopita, tiropita and kolokithopita). The pie looks crusty all over - just like all the other pitas - but with less filo on the top than the other ones.

When googling a recipe, I always check the images. After picking the galatopita photos that I liked, I then opened the page of whichever one took my fancy. Here's what I found:

- some use no filo at all (they're baked like a custard)

- some use filo only on the bottom (they're baked like a pie)

- some use filo both on top and at the bottom (like the one I tried in Karpenisi)

- some pour syrup over the baked (filo or filo-less) pie (in other words, they turn out like a galaktoboureko).

There were also some interesting variations, eg nuts/dried fruit in the custard, flavoured custard (notably chocolate) and variations on the way the pita is presented (eg cigar-shaped roll-ups).

Of all the recipes, I have to say that I liked the chocolate galatopita most of all, with its airy-looking crust. The combination and contrast of the pale fyllo and dark custard made it look quite pretty, and very festive. It would make a spectacular Christmas dessert, made as individual servings. It's been a while since I used my ramekin set; now is the perfect time to take them out. The following recipe is based on Asproula's galatopita recipe (in Greek); she also makes her own filo pastry for all her pitas.

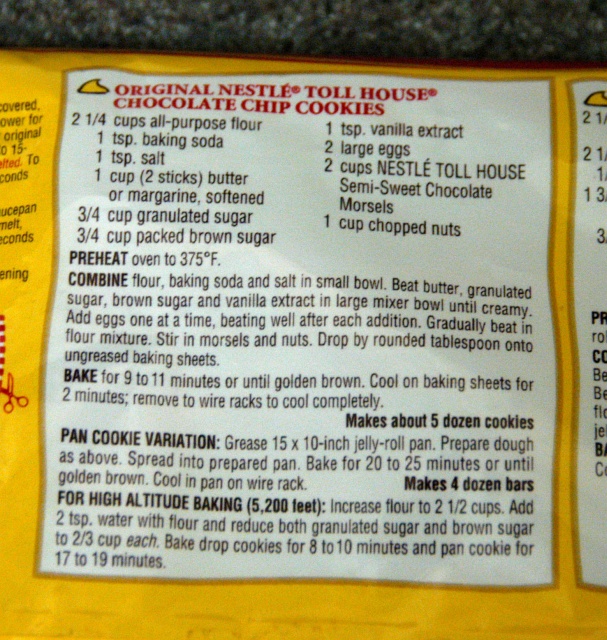

For 12 small ramekins (individual servings), you need:

3 1/2 cups of milk

1/2 cup of fine semolina

1/3 cup of butter (I use olive oil)

3 tablespoons of cocoa powder

1/2 cup of sugar (you can add more sugar if you like your custard to taste very sweet)

2 eggs

cinnamon

4-6 sheets of filo pastry (I make my own)

Warm the milk in a saucepan, then add the semolina, stirring continuously so that the mixture doesn't stick to the saucepan, and making sure that it doesn't go lumpy, until it thickens to a cream. Turn off the heat and allow the cream to cool slightly. Add the butter, sugar and sifted cocoa and mix well. Finally beat in the eggs and whisk them into the cream, blending everything well.

Grease your ramekins (I use olive oil: you can use butter) and line each one with a small piece of filo pastry, leaving a little (but not too much) pastry hanging over the edge of the ramekins. Grease the filo well and then lay another piece of pastry on top of it. Sprinkle each ramekin with a little sugar and cinnamon (which I forgot to do!), then fill each one carefully (so as not to stain the edges of the filo, like I did!) with the creamy mixture. Try to make the filo pastry stick decoratively over the edge of the ramekins (this will be easier with store-bought filo pastry); grease these pastry bits well. Place the ramekins in the oven on the lowest rack and bake in moderate heat (180C) for approximately 35-40 minutes, until the cream has set. Turn off the oven, let the galatopita ramekins sit for a few minutes to solidify, and then remove them.

My home-made filo pastry turned out quite thick, which I put to good use: it made the perfect crispy wafer to dip into the custard as we ate the pie. Because I didn't add much sugar to the dessert, I added some kind of sweetener (which is completely optional): chocolate snow, icing sugar, Greek home-made spoon sweets, honey and ground nuts all make a delicious topping to this festive dessert.

My preferred way of enjoying galatopita - the day after it's baked, for breakfast. I only had enough filo pastry for 6 ramekins, so I made the remaining 6 galatopites as 'naked' pies. The result: a velvety custard treat.

Bonus holiday recipes, from my friends:

Kiki Vagianos from the The Greek Vegan - Melomacarona Cookies

Athena Pantazatou, Kicking Back the Pebbles – Grandma Chrysoula’s Kourabiethes

Mary Papoulias-Platis, California Greek Girl - Bittersweet Chocolate Date Nut Baklava

©All Rights Reserved/Organically cooked. No part of this blog may be

reproduced and/or copied by any means without prior consent from Maria

Verivaki.